A recently published survey has found that environmental scientists in Australia are under increasing pressure from their employers to downplay climate science research findings or avoid communicating them at all. More than 50% of respondents said that constraints on communicating scientific evidence on threatened species, mining, logging and other threats to the environment had become worse in recent years.

—

Published in Conservation Letters, the survey shows how politicised debates around environment policy in Australia have become. Saul Cunningham, an environmental scientist at the Australian National University in Canberra, says, “We need our publicly funded institutions to be more vocal in defending the importance of an independent voice based on research.”

This “science suppression” hides environmentally damaging practices and policies from public scrutiny, which is detrimental to nature and democracy. Australia has a host of environmental problems, thanks to climate denial within the ranks of the government, that without scientific research, would go unknown or miscommunicated.

The Research

220 scientists in Australia responded to the survey, which was put together by the Ecological Society of Australia and ran from October 2018 to February 2019. Some of the respondents worked in government, while others worked in universities or in industry, such as environmental consultancies or NGOs.

As to be expected, the results showed that those scientists working in government or industry experienced greater constraints from their employers than university staff. Among government employees, about 50% were prohibited from speaking publicly about their research, compared to 38% in industry and 9% in universities. 75% also reported self-censoring their work.

Of those respondents that had communicated information publicly, 42% said they were harassed or criticised for doing so. 83% of these believed the harassers were motivated by political or economic interests.

One-third of government respondents and 30% of industry employees also reported that their employers or managers had altered their work to downplay or mislead the public on threatened species, as well as the environmental impacts of harmful activities such as logging and mining. Government employers most commonly altered science reported for the media or for internal communications, but conference presentations and journal articles were also altered to downplay environmental impacts.

Don Driscoll of Deakin University just outside Melbourne and lead author of the study, says that while university scientists report fewer restrictions on communicating their work, they can experience pressure that can prevent them from speaking out. He says, “Many prominent researchers in my school receive threats of violence as a result of their work. That’s “not going to be good for your mental health, and it might also shape your willingness to speak publicly about contentious issues.”

Just under 50% of respondents reported being harassed or criticised for speaking out.

The consequences of suppressing research on various aspects of the environment and climate is that vested interest groups dominate public debates and could mislead people. Additionally, relevant data is not used to inform policies.

In 2015, it was found that Australia’s peak oil and gas industry lobby group spent nearly AUD$4 million trying to obstruct more ambitious climate change policy, mostly by the Australian Petroleum Production & Exploration Association. It also lobbied to remove Australia’s renewable energy target.

InfluenceMap, a UK-based climate think tank, fingered the Minerals Council of Australia, the Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry and the NSW Minerals Council as those organisations most responsible for undermining climate policy in Australia. The report found that there has been limited public scrutiny of these activities, most likely because of climate science suppression in Australia. This has an impact on public perception of climate change and the actions needed to curb it.

An analysis of Australia news consumers found that 18% of people think that climate change is not a serious issue. Of those, 10% said the issue was “not very serious,” while 8% said it “not at all serious.” Another 15% said they do not pay attention to news about climate change at all. Consequently, the country is ranked third in the world for climate change denial, behind the US and Sweden.

This could be because of the media landscape in the country, which is one of the most concentrated in the world. News Corp newspapers- which account for 60% of newspaper sales in Australia- frequently espouses climate change denial content, with The Australian’s associate editor once saying that climate change was “not the era’s burning issue,” and the paper published an article that argued the climate change activists were “global catastrophists” and “part of a socialist plot.”

You might also like: What Amy Coney Barrett’s Confirmation to the US Supreme Court Could Mean for Climate Change

How Can We Fix It?

Driscoll suggests that one way to reduce external interference and improve transparency is to establish an independent environment commission that provides policy advice and has guaranteed funding. He adds that the commissioner in charge of the operation would need tenure “so that they can’t be sacked every time there’s an election,” as was the case in 2013, when a newly-elected conservative government disbanded a climate commission set up two years previously to act as an advisory board on climate science to the government of Australia.

Additionally, there should be policies and codes of conduct that stipulate how science should be communicated. This is seen in Canada, where the government adopted a scientific-integrity policy which directs departments employing scientists to ensure that communication is free from political, commercial and stakeholder interference.

Australian scientists aren’t the only ones who have reported pressure from employers- especially government- to downplay research findings. Those in the US, Canada and Brazil have also reported such intrusions in the past decade. A 2013 survey of more than 4 000 Canadian government scientists found that 24% of information for the media was altered or excluded for non-scientific reasons.

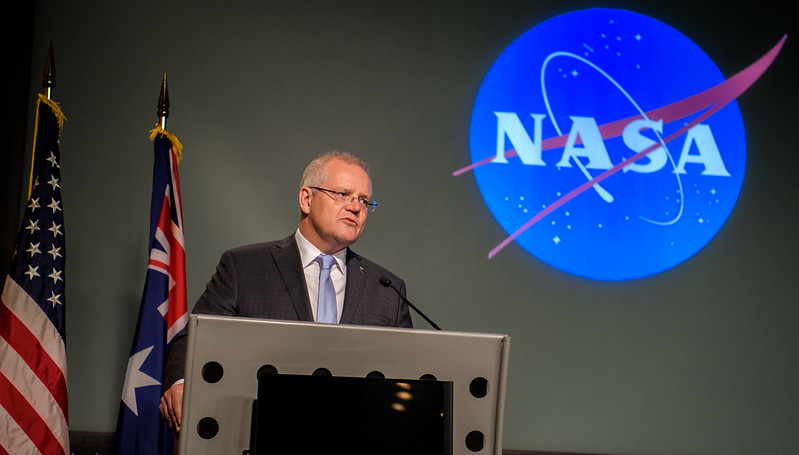

Featured image by: Flickr