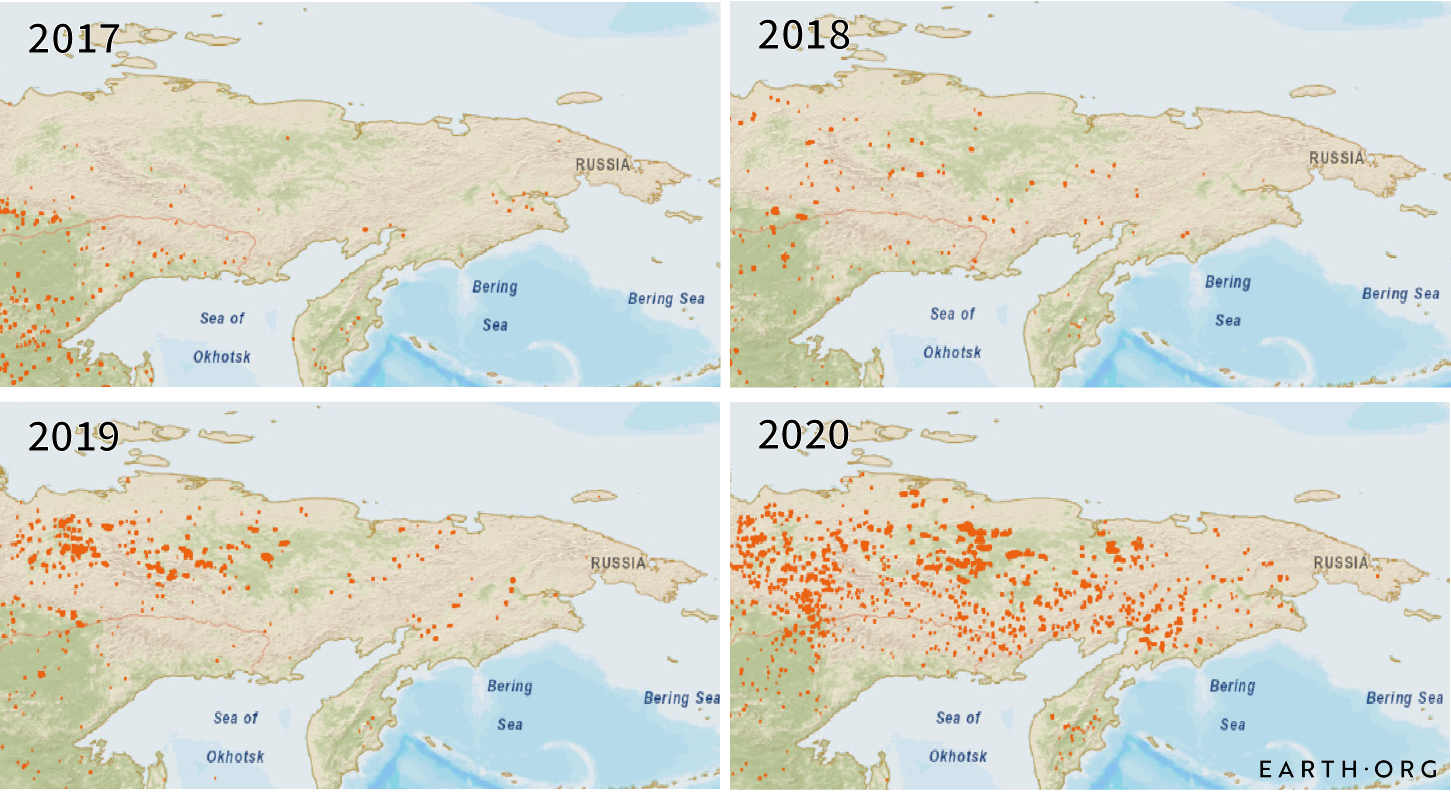

A prolonged heatwave in the Arctic that caused temperatures to soar to 38℃ in parts of Siberia, is causing wildfires to rage through parts of Siberia, Alaska, Greenland and Canada. In June, fires in the region emitted 16.3 million tons of carbon- or about 60 million tons of carbon dioxide, the highest levels since 2003 and almost nine times more than the same month in 2018. Earth.Org has compiled satellite images capturing the fires.

—

The Arctic is warming twice as fast as the rest of the world. With the rise in temperature and heat comes increased dryness, causing the soil and permafrost to lose their moisture. This extreme dryness, combined with the rise in temperature, creates an optimum environment for wildfires to flourish. Dried peat is of particular concern as the large amounts of stored carbon allow it to burn rapidly and efficiently.

The region is considered a tundra biome: a cold, dry desert with sparse vegetation apart from shrubs and mosses. Underground, permafrost resides, which significantly slows down the rate of peat decomposition, storing carbon as a result. When it thaws however, methane is released, making the conservation of peatlands vital.

Arctic Heatwave

Europe’s Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service shows that the fire activity has been further to the east in the Siberian Arctic than in 2019, with more widespread fires in the non-Arctic parts of eastern Siberia. Mark Parrington, CAMS senior scientist, says, “It is very surprising how similar the daily trend in the fire activity has been compared to 2019, especially as it is so unusual to all the other years of data that we have.”

Throughout the heatwave, some parts of the Arctic registered temperatures as much as 16℃ higher than usual in May.

The fire season typically starts in early May and picks up at the beginning of June, but it started earlier this year, with satellites registering wildfires as soon as March. Fires generally burn through forests and peatlands in Siberia. The dry vegetation on these plains can burn under the snowpack of winter and satellite data suggested that high temperatures were reigniting these ‘zombie fires’. The warm air spreading from Siberia across the Arctic doesn’t directly cause fires, but together with low soil moisture levels and low precipitation, it can contribute to conditions conducive for fires to spread.

The summer of 2019 endured record-breaking levels of smoke and smog throughout the Arctic tundra and surrounding forests. In just two months, it was estimated that approximately 100 intense wildfires spanned Alaska, Siberia, Canada and Greenland, with some reported to be ‘as big as 100 000 football fields’. In Siberia alone, the wildfires burned for 3 months and consumed over 4 million hectares of forest.

As the areas within and surrounding the Arctic Circle tend to be remote, fires can burn indefinitely, jeopardising carbon stores and releasing greenhouse gases into the atmosphere that have knock-on effects on the rest of the world.

“Fires are a natural part of the ecosystem, but what we’re seeing is an accelerated fire cycle: we are getting more frequent and severe fires and larger burned areas,” said Liz Holy, a researcher at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Centre in Maryland.

You might also like: Atmospheric CO2 Mirroring Levels Seen 15 Million Years Ago

Siberia

This summer, the fires have already burned through 333 000 hectares of land, according to Greenpeace. On June 20, the meteorological service of Russia recorded a peak of 38℃ in Verkhoyansk, the highest recorded temperature since records began in the late nineteenth century. Siberia is renowned for having a wildly fluctuating climate, holding the world record for temperatures ranging from -68℃ to 37℃.

Climate scientists have stressed how ‘alarm bells should already be ringing’- especially in response to the catastrophic effects the Arctic wildfires will have on amplifying the rate of global warming.

Another component essential for the unprecedented levels of wildfires in the Arctic is the number of storms prevalent. Between the years 2012 and 2018, a total of only 3 lightning strikes were recorded in regions close to the Arctic Ocean. However in 2019, a two-day period produced approximately 48 lightning strikes. The combination of lightning and dried earth propagates the energy and fuel required to start fires.

Moreover, the soot produced by the Arctic’s wildfires can be detrimental to humans and animals alike, inducing fatal chronic health conditions such as asthma attacks and strokes. The soot also contributes to the rising temperatures of the Arctic by settling on layers of ice and decreasing the albedo value of such surfaces- resulting in an increase in heat absorption and a decrease in light reflection, and therefore reinforcing the Arctic warming cycle.

Estimates from 2019

According to an article published by Harvard University, one peat fire can produce approximately 80 tons of carbon per acre, the equivalent of ‘the annual emissions of around 20 cars’. Estimates suggest that the Arctic wildfires in 2019 produced a total of approximately 140 million metric tons of greenhouse gas emissions- the equivalent to ‘the annual emissions of over 20 million cars’.

Though predictions are not always accurate, and have previously underestimated the fires which occurred last year, they do help researchers understand what is yet to come. Satellite images assist to monitor the fires by allowing experts to analyse characteristic smoke patterns and to measure heat output.

In addition to reducing human activities that dehydrate the Arctic fringes, researchers suggest ‘actively re-wetting the peatlands and removing plants that could fuel a fire and replacing them with mosses that can keep the ground wet’. Though this method has not been tested on a large scale, such innovation demonstrates that attempts of combating and mitigating the Arctic wildfire problem is hopefully underway.

Featured image by: Western Arctic National Parklands