New research shows that tropical forests are taking up less carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, reducing their ability to act as ‘carbon sinks’ and instead becoming sources of carbon. What does this mean for the future of humanity?

—

The Amazon could turn into a source of carbon instead of one of the biggest absorbers of the gas as soon as the next decade, as a result of the damage caused by loggers and farming interests and the impacts of the climate crisis, according to new research in the journal, Nature.

How much carbon is stored in tropical rainforests?

Intact tropical forests sequestered almost 50% of the global terrestrial carbon uptake over the 1990s and early 2000s, removing about 15% of carbon dioxide emissions. A new report shows that these carbon sinks are becoming saturated in both Amazonian and African rainforests, with different patterns of change.

“We’ve found that one of the most worrying impacts of climate change has already begun,” said Simon Lewis, professor in the school of geography at Leeds University, one of the senior authors of the research. “This is decades ahead of even the most pessimistic climate models.”

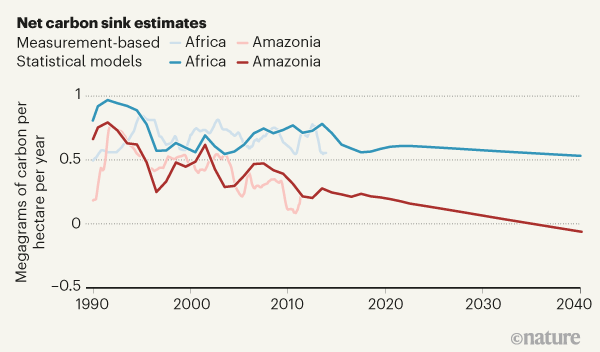

These rainforests are now taking up a third less carbon than they did in the 1990s, owing to the impacts of higher temperatures (trees have only partially acclimated to recently rising temperatures), droughts and deforestation. This downward trend is likely to continue, as forests come under increasing threat from the climate crisis and exploitation. According to Lewis, the typical tropical forest may become a carbon source by the 2060s.

Tropical rainforests act as net carbon sinks when the amount of carbon gained through the establishment of new trees and tree growth is larger than the amount lost through tree mortality. In these circumstances, the quantity of carbon stored in the biomass increases over time.

The researchers of the study monitored tree establishment, growth and mortality in 244 undisturbed forest plots in Africa across 11 countries between 1968 and 2015. This data was then compared with similar measurements from 321 plots in the Amazonian region. The results showed that carbon uptake in the Amazonian region started to decline around 1990, whereas signs of a potential slowdown in Africa appeared in 2010.

The uptake of carbon from the atmosphere by tropical forests peaked in the 1990s when about 46 billion tonnes were removed from the atmosphere, equivalent to about 17% of carbon emissions from human activities. By the last decade, that amount had sunk to about 25 billion tonnes, or 6% of global emissions, similar to a decade of fossil fuel emissions from the UK, Germany, France and Canada put together.

According to the report, by 2030, the carbon sink in Africa will be 14% lower than in 2010-2015, while the Amazonian carbon sink will reach zero by 2035 (meaning that there will be no more net carbon uptake from the atmosphere).

The researchers say that the reason for this difference between Amazonian and African tropical forests is because of increasing mean annual temperatures and droughts since 2000 that have reduced tree growth, offsetting the increase in carbon uptake. These reductions are smaller in Africa than in Amazonia.

Further, the higher carbon gains persisted for longer in Africa than in Amazonia because the warming rate was slower, there were fewer droughts and air temperatures were generally lower (because African forests are located at higher elevations). Generally, trees in Amazonia grow faster and have shorter residence times than those in African forests.

According to the report, the carbon sink strength of the world’s two most extensive tropical forests ‘have now saturated’. Reaching emissions reduction targets counts largely on the continuation of a large tropical carbon sink, which are disappearing at a rapid rate and could soon turn into carbon sources by the end of the decade. The protection of these tropical forests as well as faster greenhouse gas emissions will be needed to prevent catastrophic climate changes.

This year’s UN climate talks, Cop26, will most likely see many countries coming forward with plans to reach net zero emissions by mid-century. This will be crucial in the fight against anthropogenic global warming.

Featured image by: Jonathan Hull