Just months after the UN announced that the ozone layer is on track to fully heal by 2040, a new study revealed that the 2020 Australian bushfires contributed to its depletion, raising concern about the layer’s recovery in a warming planet.

—

Changes in atmospheric chemical composition were observed over Southern Hemisphere mid-latitudes following the 2020 Australian bushfires, suggesting that smoke from the fires depleted the ozone layer, new research suggests.

According to the study, published Wednesday in Nature, smoke from the 2019-2020 Australian bushfires – which burnt 42 million acres, destroyed thousands of buildings and killed dozens of people and up to 3 billion animals – temporarily depleted the ozone layer by 3% to 5%.

It is not the first time that scientists have warned of the threats that wildfires pose to the ozone layer. A study published early last year suggested that smoke from the 2019-2020 Australian bushfires resulted in a 1% decrease in the ozone in March 2020, already a significant number if considering that it takes a decade for the ozone layer to recover 1-3%. In another study published around the same time, researchers found that wildfire smoke led to a rise in compounds, such as hypochlorous acid, which react with ozone molecules to break them apart.

You might also like: 3 Things to Know About Australia Wildfires and Bushfires

The ozone layer is a region of the earth’s stratosphere that serves as a protective shield against the sun’s ultraviolet radiation, where exposure can result in increased risks of skin cancer. Its loss was once regarded as humanity’s most dangerous environmental challenge.

First used for fridges in 1928, it was not until the 1970s that scientists realised chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) could react with atmospheric ozone, producing oxygen and depleting the protective ozone layer. Once this was established, a global effort was made to combat the use of CFCs in household applications like refrigeration units, air conditioning, and aerosol cans. The Vienna Convention for the Protection of the Ozone Layer, first formed in 1985, and its Montreal Protocol, adopted in 1987, represented the first global effort to combat human-driven climatological effects.

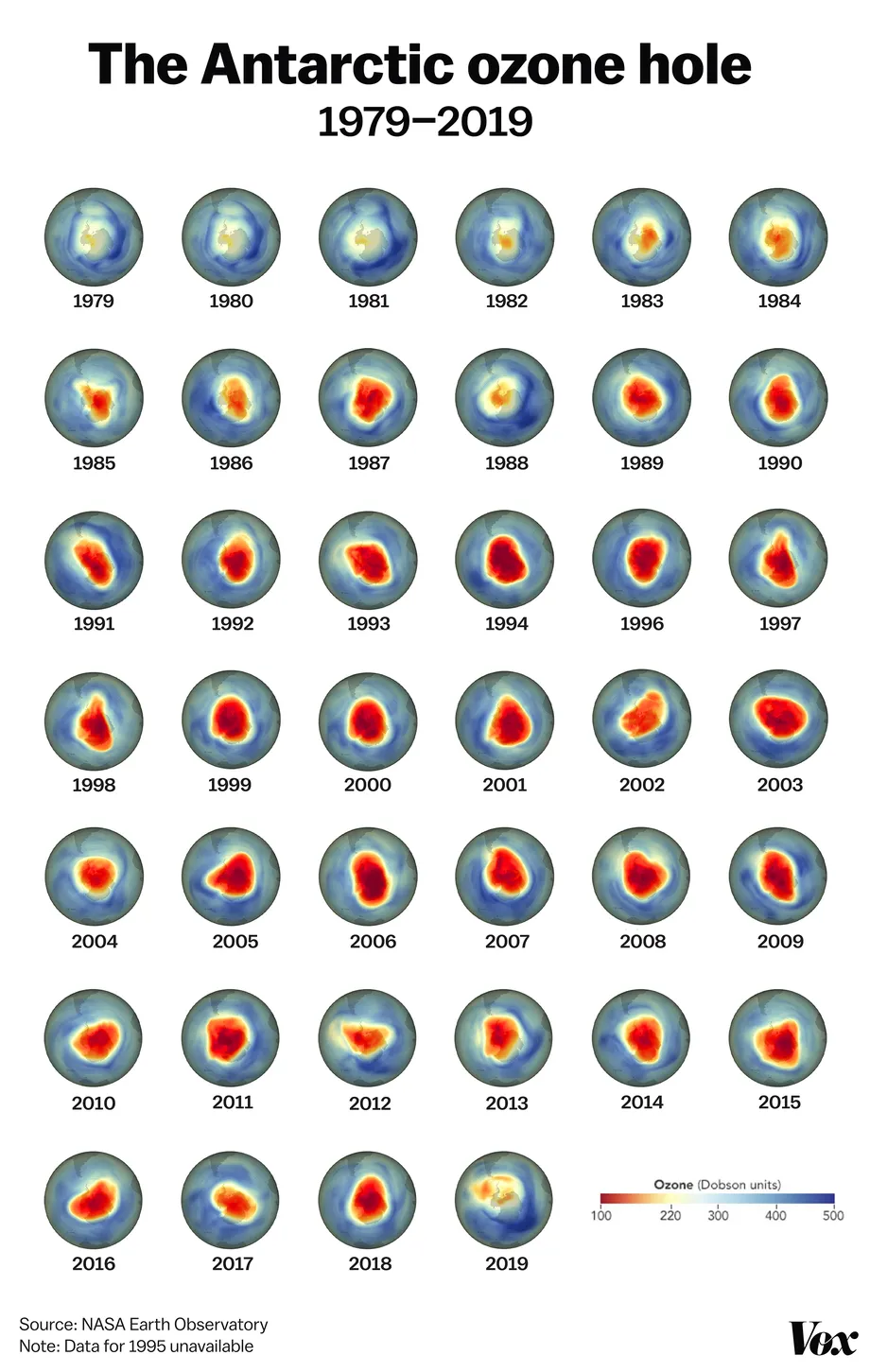

After countries agreed to phase out CFCs under the Vienna convention, the hole in the ozone shield kept growing until the year 2000. During this period, however, bromine and chlorine levels in the Antarctic stratosphere declined by 16%. Fast forward to 2019, and the ozone hole had diminished to its smallest since the 1980s at a peak area of 16.4 million km2.

The extent of ozone depletion in 2019 was the smallest in almost 40 years of satellite records and observations. Source: NASA Earth Observatory Image, developed from data gathered by NASA Ozone Watch and Global Modelling and Assimilation Office.

“In the absence of any major changes, we expect that stratospheric chlorine concentrations will gradually decrease this century and that the ozone hole will get smaller year by year,” Dr Laura Revell, an atmospheric scientist at the University of Canterbury in New Zealand, told The Guardian.

“Of concern is that while the ozone hole usually forms over Antarctica because of the cold temperatures there, wildfire aerosols appear to be capable of promoting ozone losses at the relatively warmer temperatures present at mid-latitudes which are heavily populated.”

The findings come just months after the United Nations and the World Meteorological Association announced that the ozone layer is on track to being fully healed by 2040. But while the ozone layer’s recovery remains one of history’s most successful climate restoration stories, scientists warn that changes in policies and climate change-related events such as wildfires could still delay the recovery.

You might also like: Ozone Layer Restoration Is Back on Track as Harmful Chemicals Phased Out, UN Says