Tropical regions including Northern Australia could experience extremely hot weather most days of the year by the end of the decade. Extreme heat will also occur three to 10 times as often in western Europe, the US, China, and Japan, a new study found.

—

Even if the world meets the Paris Agreement of limiting global warming to 2C, the risk of dangerous heat occurring across the tropics will “likely increase by 50-100% […] and increase by a factor of 3-10 in many regions throughout the midlatitudes”, new research suggests.

These changes refer to the global Heat Index – a metric combining air temperature and humidity to quantify the actual heat exposure in human beings.

The study, published on Thursday in the journal Communications Earth & Environment, suggests that “anthropogenic CO2 emissions will increase global exposure to dangerous environments in the coming decades.”

The team of researchers at Harvard and the University of Washington combined historic climate data with future projections of population and economic growth as well as carbon emission scenarios to estimate global temperatures in the future.

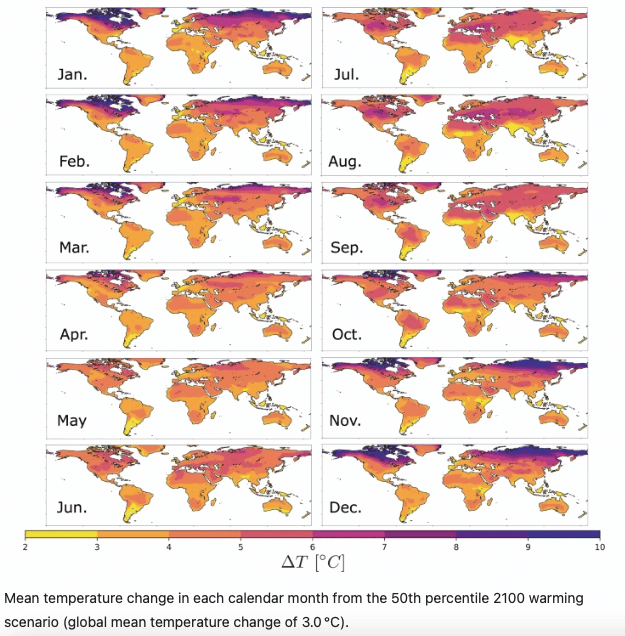

Image 1: Local temperature change across months in 2100

Despite the scenario for 2100 indicating changes over land regions are typically 5C, with even greater increases in the Arctic region, how high temperatures will rise “hugely” and ultimately depends on our ability to curb emissions in the coming decades.

In the tropics, up to half of the days in a year will have “dangerously hot” weather – meaning they will reach or surpass 39.4C. In tropical regions, the “extremely dangerous” heat index threshold – when temperatures reach 51C – will likely be exceeded on more than 15 days each year.

“The health consequences of regular very high temperatures, particularly for the elderly, poor, and outdoor workers, would be profound and require a basic reorientation to the risks of extreme heat,” the researchers found.

“The difference between being very proactive and limiting carbon emissions to keep within those parameters set forward by the Paris agreement, and not doing that, is just hugely consequential for billions of people, primarily throughout the global south,” said Lucas Vargas Zeppetello, one of the lead authors of the study.

“The difference between the two case scenarios is sort of night and day.”

You might also like: The Key Takeaways From This Summer’s Heatwaves