Hong Kong has been dealing with a monumental waste problem for years and plastic pollution is getting out of control. The city’s beaches and waterways are drowning in plastic and nearly 6,000 marine species are now considered endangered. Mainland China’s recent refusal to recycle Hong Kong’s food containers amid its fifth wave of the coronavirus pandemic exposed the underlying issues of the city’s waste management. Unsustainable packaging habits, low public awareness, and a worrisome lack of adequate recycling facilities are some of the causes of a waste management crisis. Hong Kong needs to come up with a plan to deal with its plastic waste before it is too late.

—

Why Are Hong Kong’s Streets Flooded with Plastic Containers?

The fifth wave of the coronavirus pandemic in Hong Kong that began in the first weeks of 2022 saw the city overwhelmed by a myriad of problems. Amid growing criticisms of flip-flopping pandemic measures and low vaccination rates, plastic waste became one of the biggest problems to emerge in the city. The issue arose after mainland China declared they would not take back styrofoam food containers that Hong Kong relies so much upon to import its fresh food supplies. Mainland wholesale markets, which typically receive most of the city’s containers back to reuse them, justified the decision by raising concerns over elevated risks of contracting the virus from the boxes. In a matter of days, hundreds of containers quickly started to accumulate outside of wet markets and supermarkets. During the Chinese New Year, Hong Kong’s environmental group Missing Link- Polyfoam Recycling Scheme finally publicly denounced the situation.

Styrofoam is a popular brand name for polystyrene, a petroleum-based plastic commonly used to store and transport food supplies. While it is very cheap, extremely light (it is made of 95% air), and good for insulation, styrofoam is also incredibly challenging to recycle, mainly because of the large size of the boxes and because these are often contaminated and covered in tape. The cleaning and decontamination process represents a burden and brings logistics and recycling costs up.

Together with other small recycling organisations, the government-funded organisation started handling the containers that piled up across the city. However, with limited capacities and resources to deal with such a big amount of waste – growing by an estimated one tonne a day – and with little help from the Environmental Protection Department (EPD), boxes kept piling up. A clear sign that plastic waste management in Hong Kong needs stronger reforms. Let’s take a look at how the city has been dealing with plastic waste up until now.

You might also like: 6 Biggest Environmental Issues in Hong Kong in 2022

Hong Kong’s Plastic Problem

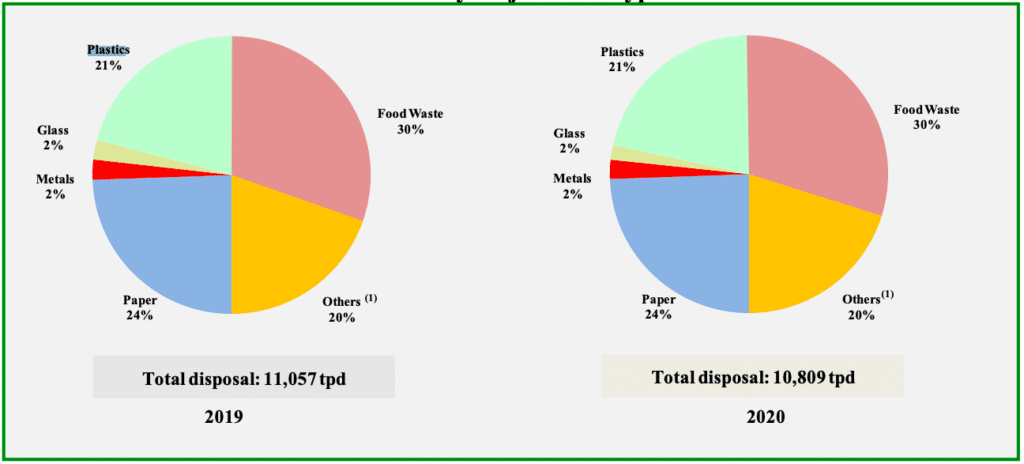

For years, Hong Kong has been dealing with a massive waste problem, and the plastic pollution issue is at a crisis point. In 2020, plastics made up 21% of the city’s total municipal solid waste (MSW), accounting for the third-largest share of MSW after food waste and paper. In the same year, Hong Kong also experienced a 27% increase in locally recycled plastics, a promising sign that some of the new measures implemented by the government, such as the Plastic Recycling Pilot Scheme, are working. Yet, plastic waste is still a huge concern for the city: its beaches and waterways are drowning in plastic, and microplastic levels in the sea are 40% higher than the global average. According to estimates, more than 5,000 pieces of microplastic can be found in every square metre of sea. Many factors contribute to Hong Kong’s plastic problem, from the city’s unsustainable packaging habits and low public awareness of the dangers of plastic pollution to a lack of adequate recycling facilities.

Figure 1: Composition of Municipal Solid Waste disposed of at landfills in Hong Kong in 2019 and 2020. Image: GovHK

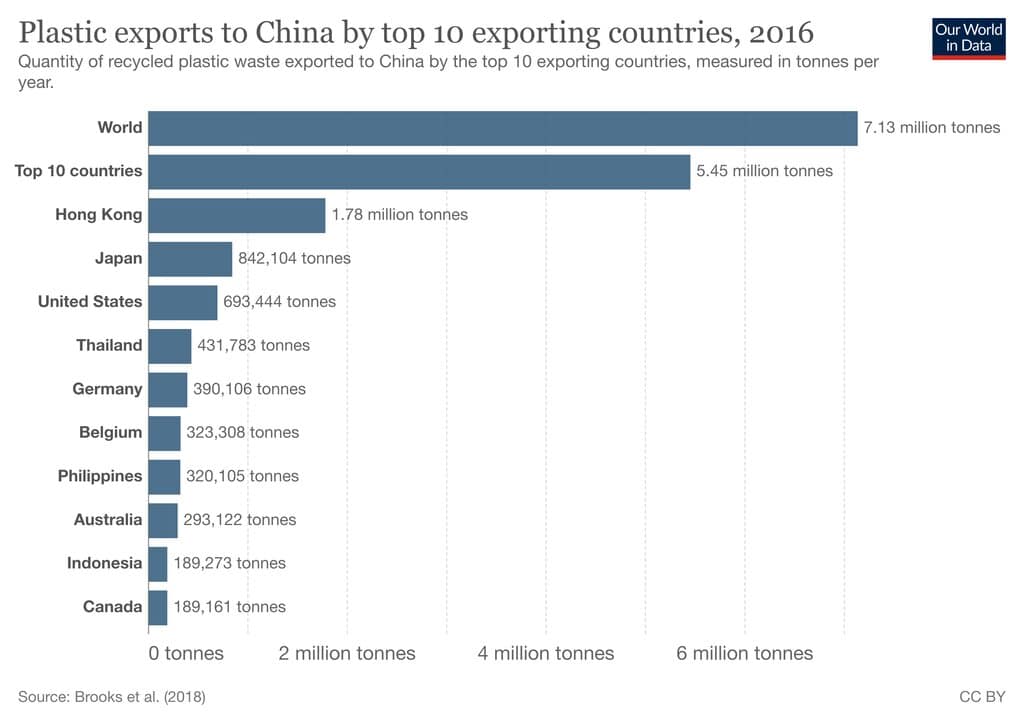

The problem with styrofoam boxes has also been going on for years. In 2017, 30,400 tonnes of such containers were disposed of at landfills. Two years later, the amount of styrofoam waste grew to 49 tonnes, or about 0.4% of the total plastic trash accumulated in the city in 2019. Currently, Hong Kong lacks a large-scale commercial operation on styrofoam recycling and the only existing styrofoam recycling programme – a project supported under the Environment and Conservation Fund (ECF) – is getting overwhelmed by the number of containers that have been piling up in the past few months. For years, Hong Kong has dealt with accumulating waste by exporting a large portion across the border yearly. In 2016, the city exported nearly 1.78 million tonnes of recycled plastic waste to China, most than any other country in the world.

Figure 2: Top 10 Plastic Exporters to Mainland China, 2016. Image: Our World in Data.

The EPD has been striving to encourage the public and different sectors to reduce the use of single-use plastic items, especially styrofoam products with various publicity and education efforts aimed at promoting the use of more environmentally friendly substitutes. And yet, as statistics show, Hong Kong is still far from solving the plastic problem.

You might also like: What Are the Consequences of China’s Import Ban on Global Plastic Waste?

What is Next for Hong Kong in the Race to Solve its Plastic Waste Problem?

In August 2021, the Hong Kong Legislative Council passed the long-awaited Waste Charging Scheme: it is hoped that this move will help reduce per capita waste disposal by up to 45% and increase the recycling rate by 55% at the same time. However, the new scheme will not start until 2023, delaying hopes that the waste crisis will be solved any time soon.

In the meantime, Hong Kong should look at how other countries are dealing with their trash to find new ways to reduce plastic waste in the city. A good example is Macao: in January 2021, the government banned all imports and trading of disposable takeaway boxes, bowls, cups, and dishes made out of styrofoam. Similarly, in 2021 the European Union banned the use of single-use plastics across all countries, a very important step in the transition to a circular economy. While a ban on plastic cutlery at restaurants is planned for Hong Kong, this will only come into force in 2025: too late according to many environmental groups who strongly believe that faster action is needed. Taiwan’s transition from garbage island to recycling leader is another example of a success story that could serve as a lesson for Hong Kong. The government introduced a new plastic waste management framework that encourages citizens and manufacturers to adopt practices that result in less trash generated. Finally, to facilitate the recycling of beverage bottles, Hong Kong should look at the Deposit Refund Scheme (DRS), a very effective scheme implemented by governments worldwide, from Australia and North America to several countries in Europe.

Featured Image courtesy of Missing Link- Polyfoam Recycling Scheme

You might also like: The Hong Kong Waste Charging Scheme is a Good First Step, But More is Needed