As the latest IPCC Report concludes that catastrophic climate events will become even more intense and frequent in the years to come, the time has come for nations to take action and guarantee protection to the millions of citizens affected by such disasters. With several provinces as epicentres of floods and droughts, China was one of the world’s first nations to launch a mass resettlement plan for the so-called “ecological migrants”. Ecological migration aims to provide assistance as well as social and economic support to its displaced citizens while preserving the migrants’ cultural heritage and the traditional way of living when relocating them from rural to urban areas. Despite mixed results, this ambitious plan sets an example for other nations still trying to find a way to mitigate the influx of climate migrants.

—

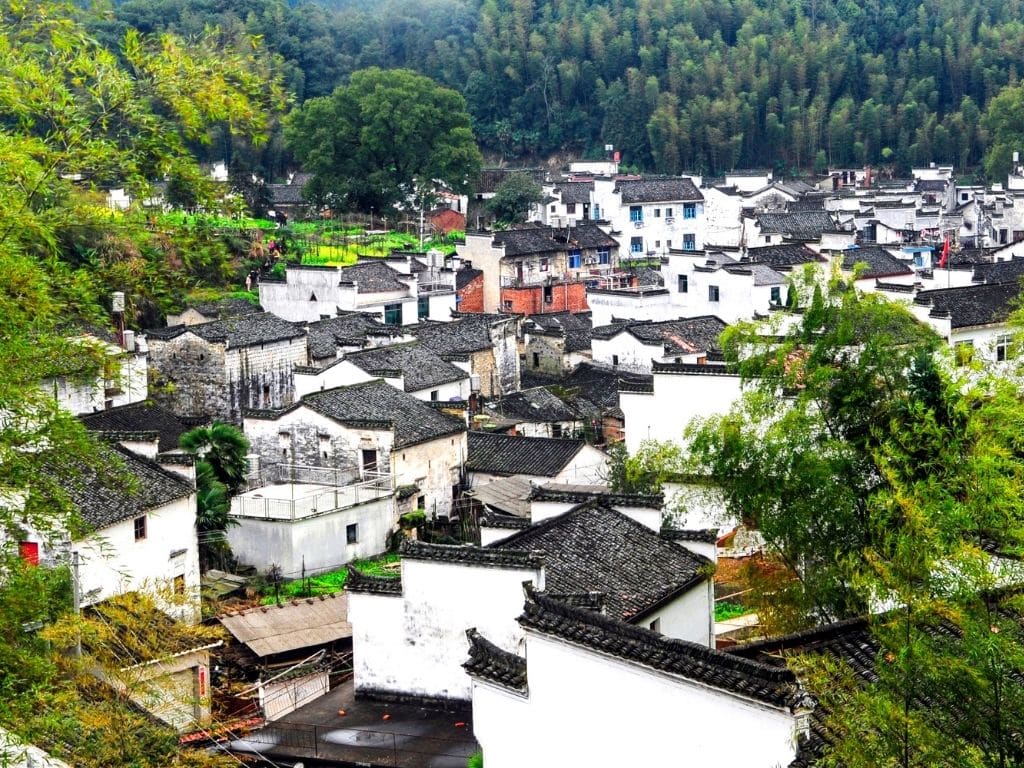

Hundreds of counties in Mainland China are imperilled by natural disasters and extreme weather caused by climate change. One of the most affected provinces is Guizhou.

Besides being the nation’s poorest areas, this province located in southwest China is characterised by a very geologically challenging and predominantly mountainous landscape. Here, nearly 3 million hectares have turned into a rocky desert in the past decades because of the impact of climate change on its Karst terrain, consisting of caves, sinkholes, and underground rivers. Because of the total absence of surface drainage, this terrain is particularly prone to groundwater flooding. In 2020, the province suffered the worst floods of the last 60 years that killed dozens of residents. But Guizhou is not the only area at risk. More recently, the central China’s Henan province has been at the centre of news after being hit by the region’s heaviest, record-breaking rainfall and some of the worst floods the region has experienced in decades.

Even though such events, in China as well as elsewhere in the world, are extraordinary and often unforeseen, they are expected to become more frequent and are destined to worsen in the coming years, as the latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report concluded.

What happened in China is just one of the many examples of catastrophic climate events that have had devastating consequences because of their intensity and destructive capacity. Of the most recent events, many took place in developed countries that were never thought to be at such a high risk of being hit, like the deadly floods that hit Germany and other European countries last June.

Besides having a catastrophic impact on the landscape and geology of the affected areas, such events are especially stressing entire communities and have a long-lasting impact on the people who inhabit these places. In 1990, the IPCC published the First Assessment Report (FAR). What they noted more than 30 years ago is something that is still very much valid today: “The greatest single impact of climate change could be on human migration – with millions of people displaced by shoreline erosion, coastal flooding and agricultural disruption”.

Indeed, what we have seen growing in the last decades is the number of people displaced by sudden and catastrophic climate events as well as slower climate related changes such as sea level rise, desertification, and water scarcity. These events, over time, turn once highly populated places in completely inhospitable areas.

You might also like: Climate Migration Is the Crisis of the Century

Even though governments around the world are finally starting to implement different policies and strategies to fight climate change, the problem of migration is more complex, and many countries are still not prepared to deal with the constantly rising influx of climate refugees which, the World Bank estimates, will concern over 100 million worldwide by 2050.

In the past decade, China has experimented a new way of enforcing environmentally induced mass migrations and creating towns to host such a huge amount of displaced people, as the catastrophic events that have afflicted provinces such as Guizhou and Qinghai over the last decades have forced Beijing to take action.

As early as 1983, China launched a mass resettlement plan for so-called “ecological migrants”, which in more recent years was expanded to become the world’s largest climate migration programme. This massive and ambitious programme aims to depopulate high-risk areas and relocate millions of rural citizens in bigger cities with a much lower ecological sensitivity. Of all Chinese provinces, Guizhou, being one of the most impacted by climate change, is therefore the one with the largest ecological migration programme: almost 2 million people have been displaced between 2012 and 2020. However, extreme weather events related to climate change are hitting other areas across the country, such as the upper reaches of the Yangtze River and the Yellow River as well as China’s southeast coast. But what does “ecological migration” really mean?

You might also like: Climate Change is Causing a Migration Crisis in Central America

Many wrongly associate the term with climate migration. However, the concept has a broader meaning. Ecological migration encompasses the environmental protection of areas whose ecosystem is at risk as well as the long-term development and well-being of migrants. This means that the relocation of people living in these high-risk and fragile ecosystems should not compromise their quality of life. Acknowledging the meaning of this term helps understanding the reasons why China wants these displacements to take place.

On the one hand, in an attempt to mitigate local environmental pressure, the country wants to act quickly to relocate people from high-risk areas affected by soil degradation from over-farming and climate change related events such as increasing droughts, rise in temperature and desertification, to safer regions. On the other hand – according to China’s National Rural Revitalization Bureau – transferring people to cities and towns is also a way to promote infrastructure construction, expand urban areas and strengthen their economy, thus accelerating the overall pace of local urbanisation. Furthermore, this top-down environmental programme foresees government mobilisation as a way to support poverty alleviation – one of the primary goals of Xi Jinping’s leadership. In his 2016 study, Dr. Zheng Yan wrote that the country’s ecological migration program is indeed a way to lift rural people in China out of poverty, in a country where 95% of those living in absolute poverty are located in ecologically-fragile areas.

At the same time, it aims at relieving the pressure on the rural population, that often lacks access to basic facilities that are considered crucial for human survival. What is more important and what makes ecological migration different from climate migration is China’s desire to preserve the migrants’ cultural heritage and the traditional way of living when relocating them from rural to urban areas.

Up until today, the world biggest relocation programme has had mixed results. Studies found that the quality of life of migrants increased, for reasons including proximity to a wide range of facilities providing basic necessities and services such as schools and hospitals. However, for many migrants, breaking with rural structures and abandoning their land – which represented their greatest source of income – compromises their financial situation. Many also find it difficult to adapt to the strict routine and fixed working hours of the jobs offered by the many relocation centres.

Furthermore, for those accepting the government’s relocation offers, it is often hard to integrate in the new communities and urban lifestyle because of language and cultural barriers. Indeed, according to surveys conducted at two ecological resettlement locations in Guizhou, 79% of those relocated – voluntarily or not – were not able to find a stable job once they moved to urban areas.

These mixed results show that China has still a long way to go if it wants to maintain its promise of preserving ecologically fragile areas while leaving rural habits and traditions intact. However, the country’s approach to the ever-rising problem of climate change-related migration might serve as an example to other nations who will have to find a way to deal with a rapidly increasing influx of migrants in the coming years.

You might also like: Top 5 Environmental Issues in China in 2023