Water is life. Yet, as the world population mushrooms and climate change intensifies droughts, over 2 billion people still lack access to clean, safe drinking water. By 2030, water scarcity could displace over 700 million people. From deadly diseases to famines, economic collapse to terrorism, the global water crisis threatens to sever the strands holding communities together. This ubiquitous yet unequally distributed resource underscores the precarious interdependence binding all nations and ecosystems and shows the urgent need for bold collective action to promote global water security and avert the humanitarian, health, economic, and political catastrophes that unchecked water stress promises.

—

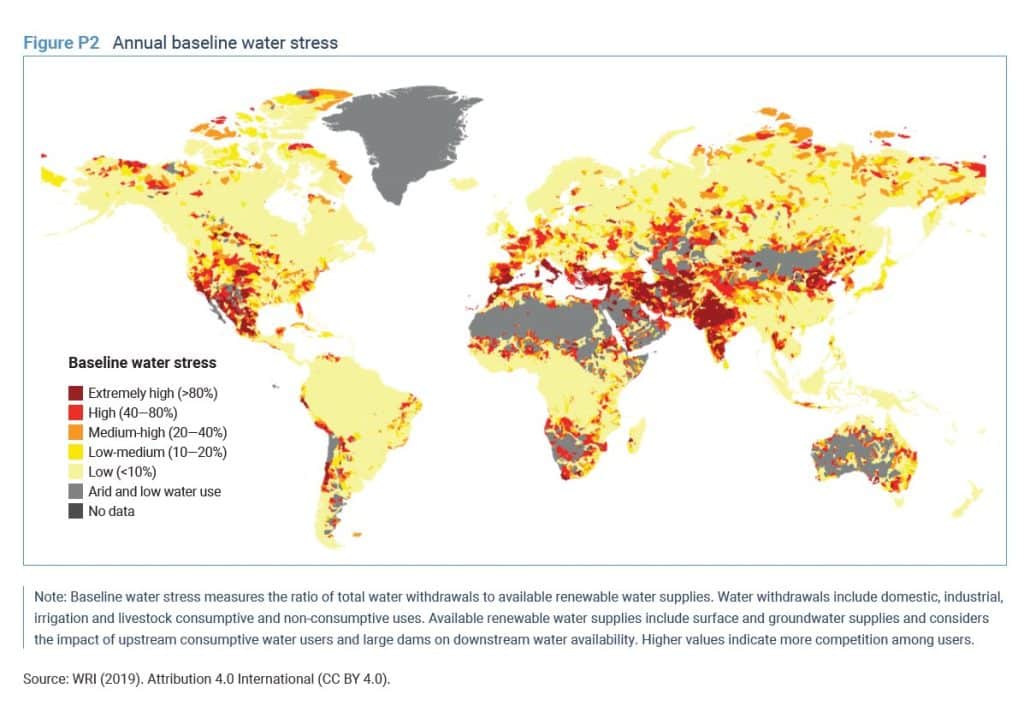

The global water crisis refers to the scarcity of usable and accessible water resources across the world. Currently, nearly 703 million people lack access to water – approximately 1 in 10 people on the planet – and over 2 billion do not have safe drinking water services. The United Nations predicts that by 2025, 1.8 billion people will be living in countries or regions with absolute water scarcity. With the existing climate change scenario, almost half the world’s population will be living in areas of high water stress by 2030. In addition, water scarcity in some arid and semi-arid places will displace between 24 million and 700 million people. By 2030, water scarcity could displace over 700 million people.

In Africa alone, as many as 25 African countries are expected to suffer from a greater combination of increased water scarcity and water stress by 2025. Sub-Saharan regions are experiencing the worst of the crisis, with only 22-34% of populations in at least eight sub-Saharan countries having access to safe water.

Water security, or reliable access to adequate quantities of acceptable quality water for health, livelihoods, ecosystems, and production has become an urgent issue worldwide.

This crisis has far-reaching implications for global health, food security, education, economics, and politics. As water resources dwindle, conflicts and humanitarian issues over access to clean water will likely increase. Climate change also exacerbates water scarcity in many parts of the world. Addressing this complex and multifaceted crisis requires understanding its causes, impacts, and potential solutions across countries and communities.

You might also like: Why Global Food Security Matters in 2024

The Global Water Crisis

The global water crisis stems from a confluence of factors, including growing populations, increased water consumption, poor resource management, climate change, pollution, and lack of access due to poverty and inequality.

The world population has tripled over the last 70 years, leading to greater demand for finite freshwater resources. Agricultural, industrial, and domestic water usage have depleted groundwater in many regions faster than it can be replenished. Agriculture alone accounts for nearly 70% of global water withdrawals, often utilizing outdated irrigation systems and water-intensive crops.Climate change has significantly reduced renewable water resources in many parts of the world. Glaciers are melting, rainfall patterns have shifted, droughts and floods have intensified, and temperatures are on the rise, further exacerbating the crisis.

In many less developed nations, lack of infrastructure, corruption, and inequality leave large populations without reliable access to clean water. Women and children often bear the burden of travelling distances to fetch water for households. Contamination from human waste, industrial activities, and agricultural runoff also threaten water quality and safety.

Water scarcity poses risks to health, sanitation, food production, energy generation, economic growth, and political stability worldwide. Conflicts over shared water resources are likely to intensify without concerted global action.

Case Study: Water Crisis in Gaza

The water crisis in Gaza represents one of the most severe cases of water scarcity worldwide. The small Palestinian territory relies almost entirely on the underlying coastal aquifer as its source of freshwater. However, years of excessive pumping far exceed natural recharge rates. According to the UN, 97% groundwater does not meet World Health Organization (WHO) standards for human consumption due to high salinity and nitrate levels.

The pollution of Gaza’s sole freshwater source stems from multiple factors. Rapid population growth contaminated agricultural runoff, inadequate wastewater treatment, and saltwater intrusion due to over-extraction have rendered the aquifer unusable.

In June 2007, following the military takeover of Gaza by Hamas, the Israeli authorities significantly intensified existing movement restrictions, virtually isolating the Gaza Strip from the rest of the occupied Palestinian territory (oPt), and the world. The blockade imposed by Israeli Authority also severely restricts infrastructure development and humanitarian aid.

The water crisis has devastated Gazan agriculture, caused widespread health issues, and crippled economic growth. Many citizens of Gaza have to buy trucked water of dubious quality, as the public network is unsafe and scarce. The United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) reports that this water can cost up to 20 times more than the public tariff, with some households spending a third of their income or more on water. Long-term solutions require increased water supplies, wastewater reuse, desalination, and better resource management under conflict.

Case Study: Water Shortage in Africa

Africa faces some of the most pressing challenges with water security worldwide. While the continent has substantial resources, poor infrastructure, mismanagement, corruption, lack of cooperation over transboundary waters, droughts, and population pressures all contribute to African water stress.

According to a 2022 report by the WHO and UNICEF’s Joint Monitoring Programme (JMP), 344 million people in sub-Saharan Africa lacked access to safely managed drinking water, and 762 million lacked access to basic sanitation in 2020. WaterAid, a non-governmental organization, explains that water resources are often far from communities due to the expansive nature of the continent, though other factors such as climate change, population growth, poor governance, and lack of infrastructure also play a role. Surface waters such as lakes and rivers evaporate rapidly in the arid and semi-arid regions of Africa, which cover about 45% of the continent’s land area. Many communities rely on limited groundwater and community water points to meet their water needs, but groundwater is not always a reliable or sustainable source, as it can be depleted, contaminated, or inaccessible due to technical or financial constraints. A 2021 study by UNICEF estimated that women and girls in sub-Saharan Africa collectively spend about 37 billion hours a year collecting water, which is equivalent to more than 1 billion hours a day.The 2023 UN World Water Development Report emphasizes the importance of partnerships and cooperation for water, food, energy, health and climate security in Africa, a region with diverse water challenges and opportunities, low water withdrawals per capita, high vulnerability to climate change, and large investment gap for water supply and sanitation.

Water security in Africa is low and uneven, with various countries facing water scarcity, poor sanitation, and water-related disasters. Transboundary conflicts over shared rivers, such as the Nile, pose additional challenges for water management.

However, some efforts have been made to improve water security through various interventions, such as community-based initiatives, irrigation development, watershed rehabilitation, water reuse, desalination, and policy reforms. These interventions aim to enhance water availability, quality, efficiency, governance, and resilience in the face of climate change. Water security is essential for achieving sustainable development in Africa, as it affects numerous sectors, such as agriculture, health, energy, and the environment.

Other Countries with Water Shortages

Water scarcity issues plague many other parts of the world beyond Gaza and Africa. Several examples stand out:

- Egypt depends largely on the Nile River, but the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam threatens water supplies. Water quality is also declining, and demand is rising with rapid population growth.

- Iraq faces severe water stress impacting agriculture and public health. The Tigris and Euphrates Rivers have dwindled because of upstream damming and climate change. Water distribution is inefficient and wasteful.

- Parts of the United States, like California, have faced prolonged droughts. Groundwater pumping has caused land subsidence, and supplies habitually fall short of demand in cities like Phoenix.

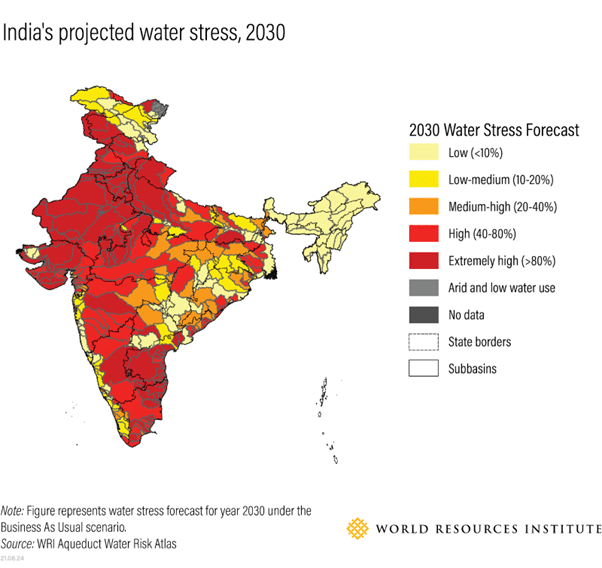

India grapples with extensive groundwater depletion, shrinking reservoirs and glaciers, pollution from agriculture and industry, and tensions with Pakistan and China over shared rivers. Monsoons are increasingly erratic with climate change.

Other water-stressed nations include Australia, Spain, Turkey, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and South Africa.

While the specifics differ, recurrent themes include unsustainable usage, climate change, pollution, lack of infrastructure, mismanagement, poverty, transboundary conflicts, and population growth pressures. But resources often exist; the challenge lies in equitable distribution, cooperation, efficiency, and sustainable practices. Multiple approaches must accommodate local conditions and transboundary disputes.

You might also like: Water Crisis in South Africa: Causes, Effects, And Solutions

Global Water Security Is at Risk

Water scarcity poses a grave threat to global security on multiple fronts.

First, it can incite conflicts within and between nations over access rights. History contains many examples of water wars, and transboundary disputes increase the risk today in arid regions like the Middle East and North Africa.

Second, water shortages undermine food security. With agriculture consuming the greatest share of water resources, lack of irrigation threatens crops and livestock essential for sustenance and livelihoods. Food price spikes often trigger instability and migrations.

Third, water scarcity fuels public health crises, leading to social disruptions. Contaminated water spreads diseases like cholera and typhoid. Poor sanitation and hygiene due to water limitations also increase illness. The Covid-19 pandemic underscored the essential nature of water access for viral containment.

Finally, water shortages hamper economic growth and worsen poverty. Hydroelectricity, manufacturing, mining, and other water-intensive industries suffer. The World Bank estimates that by 2050, water scarcity could cost some regions 6% of gross domestic product (GDP), entrenching inequality. Climate migration strains nations. Overall, water crises destabilize societies on many levels if left unaddressed.

Solutions and Recommendations

Tackling the global water crisis requires both local and international initiatives across infrastructure, technology, governance, cooperation, education, and funding.

First, upgrading distribution systems, sewage treatment, dams, desalination, watershed restoration, and irrigation methods could improve supply reliability and quality while reducing waste. Community-based projects often succeed by empowering local stakeholders.

Second, emerging technologies like low-cost water quality sensors, affordable desalination, precision agriculture, and recyclable treatment materials could help poorer nations bridge infrastructure gaps. However, funding research and making innovations affordable remains a key obstacle.

Third, better governance through reduced corruption, privatization, metering, pricing incentives, and integrated policy frameworks could improve efficiency. But human rights must be protected by maintaining affordable minimum access.

Fourth, transboundary water-sharing treaties like those for the Nile and Mekong Rivers demonstrate that diplomacy can resolve potential conflicts. But political will is needed, along with climate change adaptation strategies.

Fifth, education and awareness can empower conservation at the individual level. Behaviour change takes time but can significantly reduce household and agricultural usage.

Finally, increased financial aid, public-private partnerships, better lending terms, and innovation prizes may help nations fund projects. Cost-benefit analyses consistently find high returns on water security investments.

In summary, sustainable solutions require combining new technologies, governance reforms, education, cooperation, and creative financing locally and globally.

Conclusion

The global water crisis threatens the well-being of billions of people and the stability of nations worldwide. Key drivers include unsustainable usage, climate change, pollution, lack of infrastructure, poverty, weak governance, and transboundary disputes. The multiple impacts span public health, food and energy security, economic growth, and geopolitical conflicts.

While daunting, this crisis also presents opportunities for innovation, cooperation, education, and holistic solutions. With wise policies and investments, water security can be achieved in most regions to support development and peace. But action must be accelerated on both global and community levels before the stresses become overwhelming. Ultimately, our shared human dependence on clean water demands that all stakeholders work in unison to create a water-secure future.

More on the topic: Exploring the Most Efficient Solutions to Water Scarcity