On October 31st, the 26th session of the UN Conference of Parties (COP26) will kick off in Glasgow, Scotland. The conference was originally scheduled to take place in November 2020, but was delayed due to the global COVID-19 pandemic, allowing the summit to take place physically in relative safety. World leaders, delegates and experts from around the world will attend two weeks of what are understood to be the most important climate talks of the decade, if not the century. What should we be keeping an eye out for as the pivotal meetings begin?

—

The purpose of the UN Conference of Parties is to hold regular forums where the newest scientific information on climate change can be presented, negotiations between business and political leaders can be conducted and policy agreements can be reached. The goal is to arrive at a coordinated consensus on how the world will adapt to climate change impacts, enable economic development in a sustainable manner and reach agreements on emissions reduction and climate change mitigation.

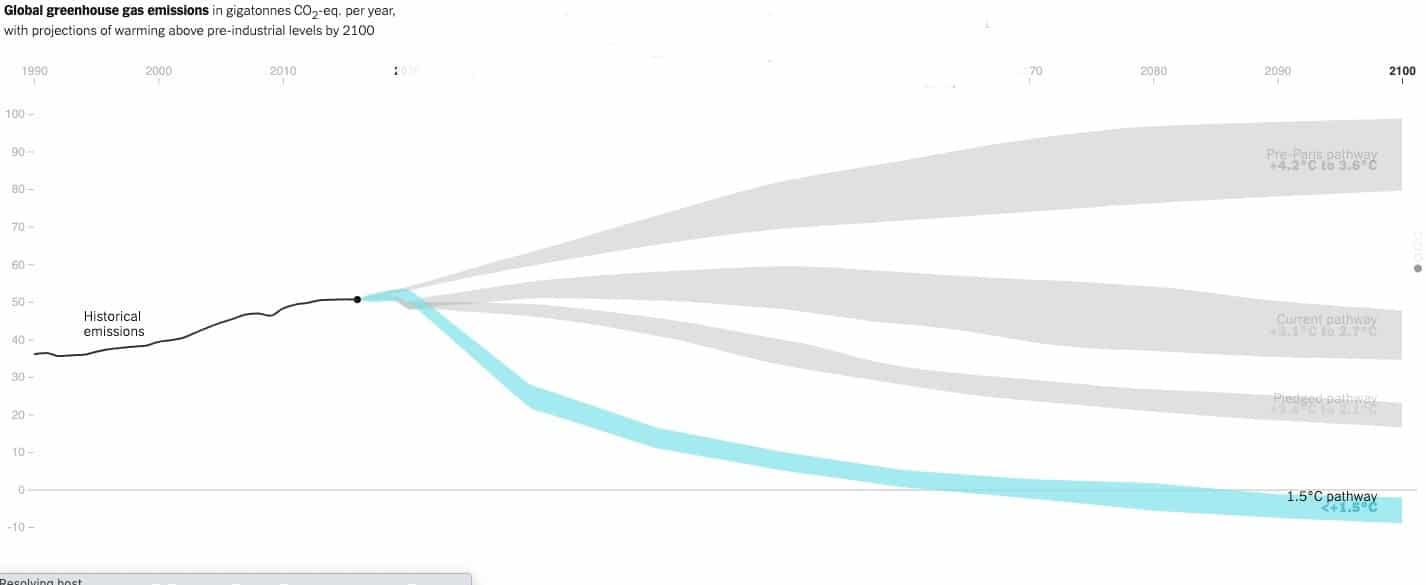

2020’s delayed session aside, the UN climate change conferences have been held annually since 1995. In 2015, at COP21 in Paris, the participating parties signed an agreement that provided a cohesive plan towards coordinated climate action, known as the Paris Agreement. The Paris Agreement calls for countries to keep global temperature averages to 2°C above pre-industrial levels, and pursue best efforts to keep warming below 1.5°C.

Since the Paris Agreement was first signed, many countries have come forward with commitments to reduce their carbon emissions and net-zero target dates. The agreement ruled that every five years on from Paris, countries would have to update their targets and pledges to reflect the latest science, and in light of 2020’s delayed conference, COP26 will be the time for leaders to do so. Since 2015, progress has been made in reducing emissions, but it’s not nearly enough. The latest UN Emissions Gap report shows that current policies will lead to 2.7°C of temperature rise by the end of the century, an outright nightmarish scenario. This is our leaders’ chance to make a stronger push for a better future.

The goal at COP26 will be to accelerate the world’s progress towards achieving the goals outlined in the Paris Agreement, to put some flesh on the framework established six years ago and to ensure that countries are on the right track. Here are the important stories to keep in mind as the session kicks off.

Who Will Be There?

Despite being delayed by a year, the ongoing pandemic is still leaving its mark on COP proceedings, and some world leaders have opted out of attending the critical climate conference, ostensibly citing health concerns.

Notable physical absentees from COP26 include Chinese President Xi Jinping, who has not left China since January 2020, months before COVID-19 was declared a global pandemic by the WHO. Despite some hope amongst counterparts that Xi would make an exception for the pivotal climate talks, it remains highly unlikely that he will be in attendance.

Russian President Vladimir Putin has also played an elusive figure throughout the pandemic, exhibiting much more stringent personal protective measures against contracting the virus than most other world leaders. The Kremlin confirmed on October 20th that the Russian President would not physically attend COP26, but would be present through virtual means.

Other notable world leaders who have opted not to attend COP26 in person include Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro, leader of the Catholic Church and occasional climate activist Pope Francis, Mexico President Andres Manuel Obrador, and South Africa President Cyril Ramaphosa. Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida has yet to confirm whether he will be in attendance or not. Several least-developed countries have also been at risk of not being able to attend the conference, given quarantine restrictions for unvaccinated travellers to the UK, high costs to stay in Glasgow, and low vaccination rates for COVID-19 in much of the developing world.

COP26’s organisers have insisted that the no-shows will not affect the conference’s proceedings, but activists and other observers have been skeptical. Informal and backchannel discussions were crucial to getting the Paris Agreement over the line six years ago, and virtual meetings might not have the same effect as physical attendance.

That the leaders of high emitters like China and Russia, first and fourth respectively in annual emissions, are not physically attending COP is certainly less than ideal, but it does not mean that the climate talks are doomed. The countries will still send large delegations to Glasgow, with Russia alone sending more than 200 representatives. Veteran Chinese diplomat and special climate envoy Xie Zhenhua will represent his country at the talks, and his historically amicable relationship with foreign counterparts bodes well for fruitful diplomatic talks.

Climate Financing

COP26 will see fresh debates over the state of international climate finance, a point of significant tension in recent years. At the 2009 COP conference in Copenhagen, world leaders agreed that developed nations and historically large emitters, such as the US and EU countries, would deliver financing to developing countries to help withstand climate change impacts and accelerate the full adoption of renewable energy.

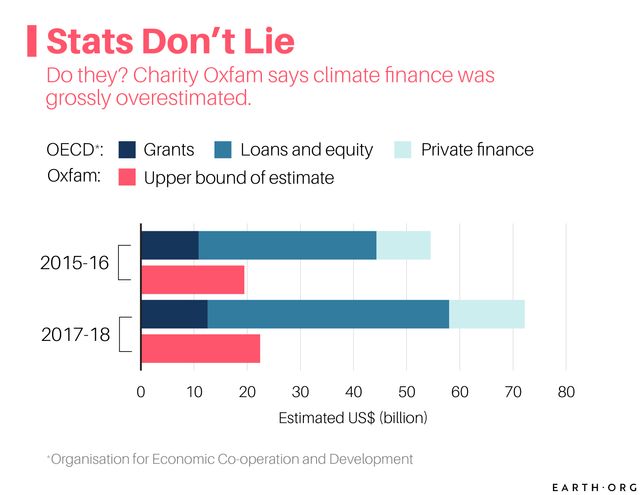

This climate finance sum was fixed at USD$100 billion each year starting from 2020, but the industrialised world has failed spectacularly at delivering on this promise. A 2021 OECD report estimated that wealthy countries delivered USD$80 billion in climate financing in 2019, but these numbers have been criticised as vastly inflated. The OECD is mainly composed of rich and industrialised nations, and further investigations found that several wealthy countries had counted the full value of some aid projects as ‘climate relevant’ even when they didn’t exclusively target climate action. A 2020 Oxfam report fixed the actual value of climate financing between 2017 and 2018 at between $19 billion and $22.5 billion.

Figure 2: How much financing have wealthy nations actually delivered to the developing world?/Graphic by Earth.Org

When wealthy countries agreed to deliver $100 billion a year in climate finance, nobody thought to discuss how to split up the cost. This has allowed the US, the world’s most egregious historical emitter, to get away with relatively minimal contributions. According to an analysis by the World Resources Institute, the US should technically be responsible for nearly half of the $100 billion financial commitment, but the country only delivered an average of $7.6 billion a year between 2016 and 2018.

The poor state of climate finance has been a particularly sensitive talking point in recent years, as developing nations have criticised the industrialised world for broken promises and wasted time. But on October 25th, only a week before COP’s kickoff date, Canadian and German representatives released a comprehensive roadmap detailing how wealthy countries plan to reach $100 billion in annual financing.

The industrialised world now believes that the $100 billion target can be reached by 2023, and will likely be able to mobilise more than that each year thereafter. But while wealthy countries express confidence in this amended target’s feasibility, developing nations are expected to discuss how the shortfall and three-year delay can be made up. India has already announced that payments for losses and missed financing will be an integral talking point for the country at the conference, and other developing nations are expected to do the same.

Climate Leaders

On the eve of COP26, nobody is really sure who is going to emerge from the climate talks as the most ambitious climate leader. Months ago, the US had been expected to take on this coveted role, and many believed that US President Joe Biden and his administration were committed to putting climate change at the forefront of America’s domestic and foreign policy. After years of languishing under former President Trump, many were enthusiastic about the new President’s chances to cement the US’s role as a global climate leader.

But a stagnating clean energy bill and a dubious carbon tax proposal later, the US is seemingly less prepared than many gave it credit for. A USD$3.5 trillion infrastructure bill has been worryingly watered down in recent weeks, putting at risk climate provisions critical to meeting the US’s goal to reduce carbon emissions by 50-52% by 2030.

Congressional Democrats are currently in the process of reworking the bill and ensuring that it passes into legislation, but time is short before COP. If Democrats are unable to come up with a solution in the coming days, then we can expect the US to come under fire in Glasgow for not matching its rhetoric with actionable policies, and the country could suffer damage to its global credibility.

The US is not the only heavyweight under pressure to impress at COP. Several countries, including South Korea and Saudi Arabia, have recently updated their pledges to reduce emissions and reach net-zero emissions, but others, like China and India, the world’s first and third largest emitters respectively, have yet to announce any updated climate pledges in the buildup to the conference. What these countries do is crucial to mitigating global climate change, so expect their actions and words at COP to be highly scrutinised.

“Our Last Best Hope”

COP26 will also take place under the shadow of the ongoing energy crisis that has afflicted the entire world, driving up energy costs and increasing uncertainty. No country has been more affected than major emitters China and India, both of which have been forced to reopen disabled coal plants and slow their transitions towards renewable energy.

The energy crisis shows that countries with high populations and energy demand need pretty much all the electricity they can get, and in times of crisis, cannot be too picky about the source. It is possible that the crisis will make China and India unwilling to phase out coal in the near-term, and the two might remain tight-lipped in Glasgow. How other countries and competitors respond, whether through pledges to commit financial assistance or through other diplomatic measures, will be a key point in the climate talks.

The energy crisis is just one external factor that might impact the talks’ outcome. The perpetually turbulent state of US-China relations is also another point of interest, as it seems unlikely that climate change can be isolated from the tense relationship between the two superpowers. Animosity between nations could come to the fore during COP, and hinder diplomatic progress. There are also logistical issues that simply come down to poor planning by the event’s organisers. Around 20,000 delegates from all over the world will be in Glasgow for the conference, a city that a year ago had fewer than 11,000 hotel beds.

But despite these issues, COP26 is happening in a vastly different context, and in a vastly different world, from six years ago. Climate change and its related impacts are now an incontrovertible truth, and even countries like Russia, which took years to ratify the Paris Agreement, have now come around to acknowledge the reality and imminent danger that climate chaos poses. The plan to equitably divide responsibilities for international climate finance is crucial, and the onus is now on the world’s wealthiest nations to do their part.

COP26 represents “the last best hope for the world,” according to US special envoy for climate John Kerry. Time is running out to get the world on track to meet the Paris Agreement’s goals, and if we want to have even a chance of staying within its parameters, it is likely that what happens in Glasgow next week will be critical.