Modern technology is revolutionising the way we practice conservation, including the way we track and monitor endangered species. In dense jungles across Borneo and Sumatra, the last refuges for Critically Endangered Sumatran and Bornean elephants, a small team of scientists, tech engineers, and university students are developing and testing a revolutionary new elephant monitoring system.

—

This article was written by Leif Cocks

The Elephant Locator Project – or ELOC for short – is using recordings of elephant vocalisations to develop an automated, vocalisation-based elephant monitoring system that can be used to support anti-poaching and human-elephant conflict mitigation measures.

The project is a collaboration between researchers and developers including those from Colombo University in Sri Lanka and Gadjah Mada University in Indonesia and is led by Dr Alexander Mossbrucker, Field Manager for the International Elephant Project (IEP).

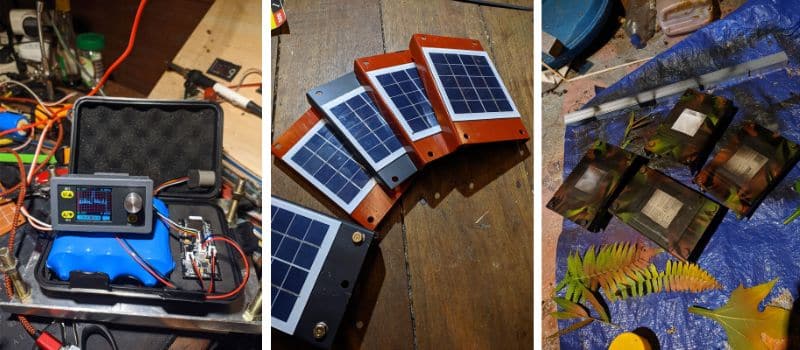

Evolution of the ELOC prototype over 18 months. Photo: International Elephant Project.

A total of 28 field-ready devices have been tested extensively in Sumatra and Borneo. The team has recorded elephant vocalisations in a number of different locations, with more than 3,000 elephant sound records labelled and analysed. Using their recording devices designed for the jungle, they discovered that some elephant vocalisations, especially low rumbles, can be detected from over 500 metres away. This is a good sign that the devices will be able to detect elephants over a long distance and can be soon used in the jungle.

Field testing and vocalisation research has been mainly implemented in Sumatra, where the International Elephant Project supports several long-term local elephant conservation projects that provide ideal testing sites characterised by high levels of conflict, intense conflict mitigation and patrol activities, as well as a considerable number of GPS-collared elephants that can be used to evaluate the new monitoring system.

You might also like: Top 10 Critically Endangered Species in Asia in 2023

Why Do We Need to Record Elephant Vocalisations?

One of the key causes of elephant deaths is human-elephant conflict, which usually occurs when elephants emerge from fragmented jungle and enter human villages and farms. They destroy crops, often trampling villagers’ huts, and occasionally even killing humans. Villagers can become afraid and fight back, seeking to defend their crops and farms. In addition to human-elephant conflict, poaching of elephants for their ivory, skin and other body parts, is also a major contributing factor to their rapid decline in the wild. Reliable elephant tracking makes it easier to deploy anti-poaching teams when and where they are needed.

Bornean elephant bulls at the edge of an oil palm plantation in the Lower Kinabatangan. Photo: International Elephant Project.

However, over the years, the use of GPS collars, which are placed around the neck of one elephant in each herd, has helped to reduce the incidences of human-elephant conflict. The collars provide rangers and community workers with data about the movement of elephants, in order to predict where they might travel next. Communities can therefore prepare in advance to defend their fields and crops with noise makers that scare the elephants back into the jungle.

While the use of GPS collars is a huge step forward in protecting elephants, the downside is that they need to be replaced regularly, which is quite difficult to do in the dense jungles of Indonesia. In addition, elephants need to be immobilised in order to exchange the collars. Hands-on work with large wildlife is always a risk and this was one of the main motivations to look for a non-invasive alternative.

The Elephant Locators could revolutionise the current method of tracking elephants, either by replacing it altogether for some herds, or at least by reducing the need for GPS collars. Together, these two methods, along with drone technology to view elephant herds from a safe distance, will enhance our ability to understand elephants and their movements, which will ultimately improve their safety and prevent conflicts with local communities.

Dr Alex Mossbrucker, Field Manager for the International Elephant Project, setting up ELOC device in the field. Photo: International Elephant Project.

How Will the Elephant Locator Work?

Elephants are known to use a rich repertoire of vocal sounds to communicate, including deep rumbles and high-pitched squeaks, as well as the classic trumpeting sounds we are used to. The frequency of these sounds ranges from approximately 9 kHz to 5 Hz. Infrasonic sound in frequencies down to about 20 Hz is capable of travelling over large distances. Accordingly, elephant calls including an infrasound component can be expected to propagate over distances over 1 kilometre (0.6 miles). By capturing these rumbles, we can therefore track elephants over long distances in dense terrain where it is not possible to see them, effectively improving our early warning systems for local villages.

Phase 1 of the ELOC project involved students from Gadjah Mada University recording elephant vocalisations over a nine-month period by deploying SWIFT records and ELOC prototypes. The recorders were placed close to semi-wild elephants and elephants being cared for in camps at the forest edge within the Gunung Leuser Ecosystem, the Bukit Tigapuluh Landscape and Way Kambas National Park, to compare the detection of elephants between the acoustic and GPS devices.

After collecting the data, recordings were screened for elephant vocalisations using the Raven Pro Sound analysis software developed by the Center for Conservation Bioacoustics at Cornell University. The result is a labelled elephant vocalisation database that is currently being used to develop a machine learning algorithm for autonomous detection.

Building upon earlier prototypes, Phase 2 of the project consists in developing a low-cost, field-deployable ELOC unit that can autonomously detect elephant vocalisations even in the remotest locations. The aim is to develop a unit that is highly energy efficient, utilising both battery and solar power, and which includes wireless and LoRa communication capabilities. If an elephant sound is detected from several recorders at the same time, the exact location can then be calculated.

Left: ELOC testing prototypes; Middle: New sturdy casing with solar panels; Right: ELOC with a custom camouflage design. Photo: International Elephant Project.

The final phase of the project is to develop an interface that will enable the sharing of obtained information with target groups (wildlife rangers, crop guards, farmers) in real time, e.g. via a mobile phone app and a system forwarding SMS. A web application will display both the localisations of identified elephants on a map as well as historical data for the purposes of later analysis and research.

Testing of the full elephant monitoring system via a pilot project is expected to take place in early 2025.

Funding for the ELOC Project has been generously provided by the US Fish & Wildlife Service, Asian Conservation Fund. For further information on the ELOC project, contact the International Elephant Project at info@internationalelephantproject.org.

Featured image: The International Elephant Project

You might also like: Using Blockchain Technology in Environmental Conservation

—

About the author

Leif Cocks is the founder of Wildlife Conservation International (WCI) which incorporates the International Elephant Project, International Tiger Project, The Orangutan Project and Forests for People. Established in 1998, WCI has raised over $26m for conservation projects across South-East Asia. Beginning his career as a zookeeper, curator and small population biologist, Leif is highly regarded as a world-renowned expert on orangutans. He is the author of a number of books including Finding Our Humanity and Orangutans My Cousins, My Friends. In 2019 Leif was awarded the Order of Australia Medal from the Australian Government for his dedication to species conservation. Visit Leifcocks.org to find out more.