The climate crisis is underscoring pre-existing global inequities. Often, the most disadvantaged are left with little voice, being spoken for rather than listened to or championed. While privileged individuals in wealthy areas can be much-needed allies, it is essential to centre the opinions and wishes of those most impacted by climate change and its effects.

—

The history of humanity is a history of injustice. Racist colonisation and imperialism. Extreme capitalism. Ecological destruction. Across the planet, the consequences are still felt to this minute. People – particularly, those most impacted – deserve to be furious about, and to criticise, the horrific past injustices that have arisen from and contributed to the inequitable systems with which we still live. And it is important to learn from the past to move forward in the most just and fair manner possible.

But, as much as we wish we could, nobody can change the past. We can only work with the world as it is, not as we wish it were.

Even for the most informed and educated among us (which in itself is a type of privilege), it is not exactly simple or straightforward to conceptualise, execute, and maintain 100% equitable solutions that benefit each and every person – and creature – on Earth equally.

The world has witnessed disastrous attempts at this. Looking back at history, one could argue that the entire 20th century was a terrifying “social experiment” demonstrating why communism and other currents of thought prevailing during that time, while being idealistic theories, simply do not work as intended in practice.

In any case, often, it is educated people in rich countries and regions with the highest HDI (“human development index”) scores who speak on behalf of those most hegemonised by humanity’s history of injustices. Including when speaking about the current climate crisis. Somewhat ironically, these well-meaning people are typically the ones who have benefited the most from history and the status quo.

Undoubtedly, those holding privileged positions of power and wealth can be much-needed allies. But, as previously mentioned, good intentions can slide into speaking for the world’s most disenfranchised and marginalised, rather than listening to and championing them.

Or, as exemplified by a Karl Marx quote, included at the beginning of Edward Said’s Orientalism: “They cannot represent themselves; they must be represented.” Relatedly, communism was a theory popularised by the intellectual bourgeoisie, not the proletariat whose interests they felt the need to represent.

The point of this piece is not to (dis)favour any political or economic system. Extreme capitalism, as currently and historically experienced around the world, has only intensified pre-existing inequalities.

As many know, the climate crisis is also a social crisis, underscoring and exacerbating obvious inequities. Not just in who is most impacted by environmental disasters but in whose voice carries the most weight.

While environmental, grassroots non-profits are serving the world’s most disadvantaged (often in the “Global South” or Indigenous communities), and doing fantastic work, the founders and board members of these organisations (especially the larger ones) usually come from positions of relative privilege and power.

Empowering people is not simply powerful people helping the less fortunate. Everyone has power. But humanity’s – aforementioned, well-documented, and rightfully well-criticised – history of injustices has resulted in a world order and societal structures where only certain forms of power are valued and listened to.

We know that even the most progressive human communities will never be perfect. There are as many nuanced views on how best to improve a community as there are people living in it.

Factors Contributing to Climate Crisis Marginalisation

Like the mental health realm is shifting towards centring lived experience, we should amplify the voices and experiential realities of those bearing the worst brunt of the climate crisis. Those who typically face multiple and/or intensified forms of adversity, discrimination, and exploitation due to their intersecting roles, attributes, and identities, e.g., based on a combination of the following factors:

- Location

- Nationality

- Socioeconomic status

- Migrant status

- Race

- Ethnicity

- Sex

- Education level

- Disability

- Age

- Religion

- Sexuality, etc.

A 2021 Earth.Org article titled “How Marginalised Groups Are Disproportionately Affected by Climate Change” outlines how economic, global, racial, and generational disparities influence which populations within which areas are particularly at risk of experiencing climate change’s most severe effects.

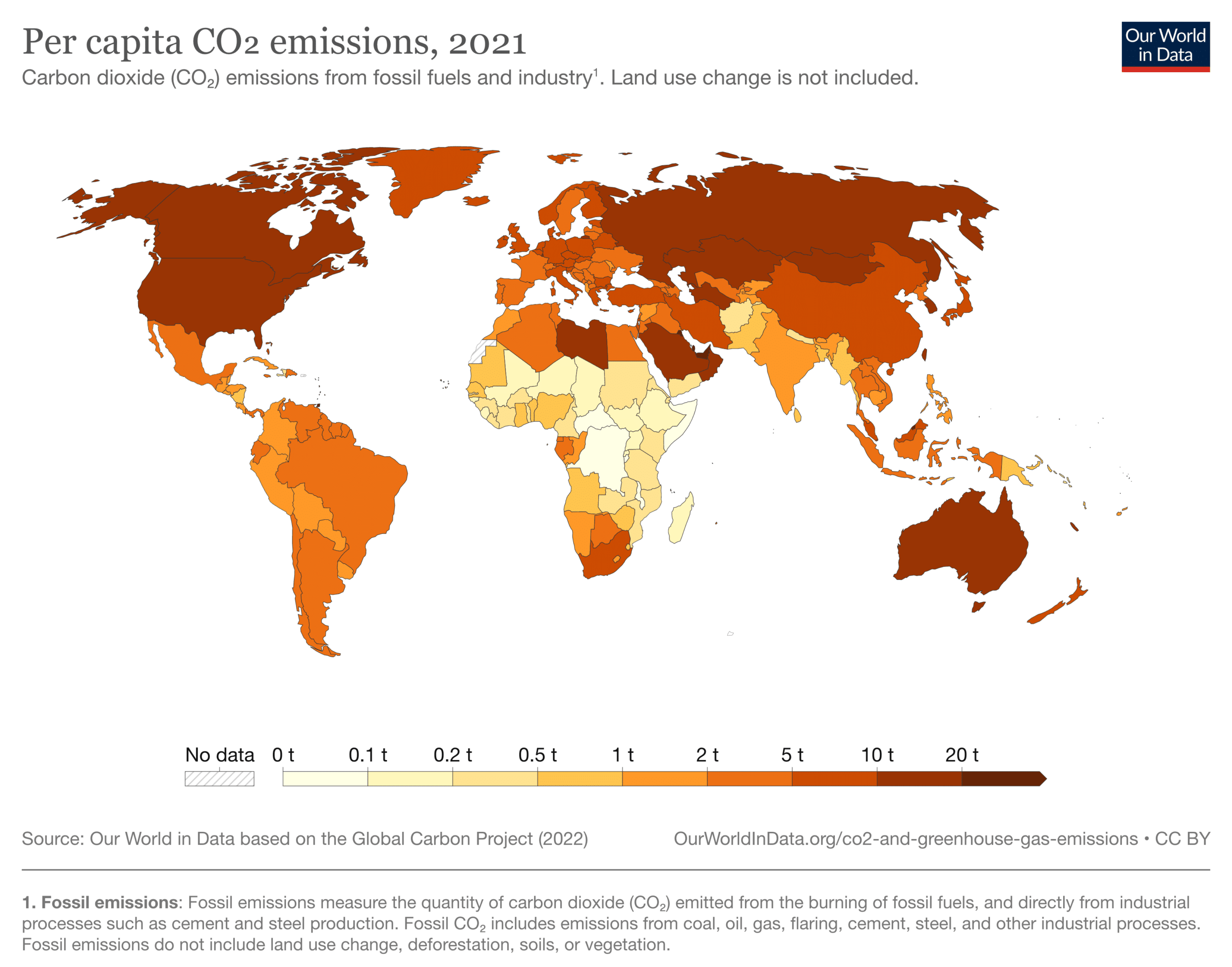

Many vulnerable nations and populations are found in the Global South. And, generally speaking, most “developing countries” are disproportionately impacted by the climate crisis. Africa in particular is unfairly hit, especially when we consider that it contributes the least to greenhouse gas emissions. In fact, Africa and South America each emit just 3-4% of the global share. Even the entirety of enormous Asia, home to China, India, and many other highly populated nations – both developed and developing – and 60% of the world’s population, contributes only 53%.

Per capita carbon dioxide (CO₂) emissions from fossil fuels and industry. Land use change is not included. Image by Our World in Data.

Disadvantaged populations within poorer areas, such as those found in Africa, South Asia, Southeast Asia, the Pacific, and South America, along with producing fewer greenhouse gases per capita, are also far less equipped to deal with the ramifications of environmental issues and disasters.

The World Economic Forum writes that the 74 lowest-income countries emit just one-tenth of emissions, “but they will be most affected by the effects of climate change.”

Another marginalising factor is gender. UN Women has called the intersection of two worldwide issues, gender inequality and the climate crisis, “one of the greatest challenges of our times.”

Due to structural inequalities, women and girls around the world have fewer human and legal rights, and less access to virtually all resources. These include land, natural resources, education, information, funding, public participation and decision-making processes, healthcare, and relief assistance.

You might also like: How the Climate Justice Movement Could Solve Global Gender Inequalities

80% of those displaced by the climate crisis are female. Globally, women are more likely than males to experience poverty. They are also likelier to face domestic violence – exacerbated by stress-inducing situations, such as those brought about by climate change. And, compared to men, women rely more on at-risk natural resources for their livelihoods (while at the same time being less likely to own these resources).

On top of these realities, women are typically the ones occupying caregiving roles within their households, looking after children and the elderly – two other vulnerable populations.

And as brought up in this piece, ecological hardships are multiplied for women who are poor, disabled, Indigenous, and otherwise marginalised and disadvantaged.

Final Thoughts

To move forward with the most equitable climate solutions, it is important to learn from historical and ongoing injustices. And diverse voices are essential for healthy democracies. But respecting the request for “nothing about us without us,” in terms of decision-making, requires us to listen to the opinions and ambitions of those with lived experience, including that of climate change’s worst impacts. Doing so can help us rectify the social inequities and injustices that the world’s environmental crisis has so far highlighted.

You might also like: What is Climate Justice and Why Is It Important?