Despite only about 0.6% of the world’s yearly greenhouse gas emissions coming from Egypt, the country is Africa’s second-largest gas producer and supplies nearly a third of the continent’s gas, with production expected to further increase significantly in the upcoming years, both for domestic use and export to the EU. Low-income populations, both in Egypt and around the world, are disproportionately affected by a number of climate change-related risks. Due to the projected rise in heatwaves, dust storms, and other extreme weather events, Egypt is particularly exposed to the effects of global warming. We take a look at how Egypt is doing about climate change.

—

Hosting COP27

Since 1995, COP summits have served as the principal international platform for climate negotiations. In the 2015 Paris Agreement, the goal of limiting the increase in the average global temperature to 1.5C (2.7F) over preindustrial levels was established.

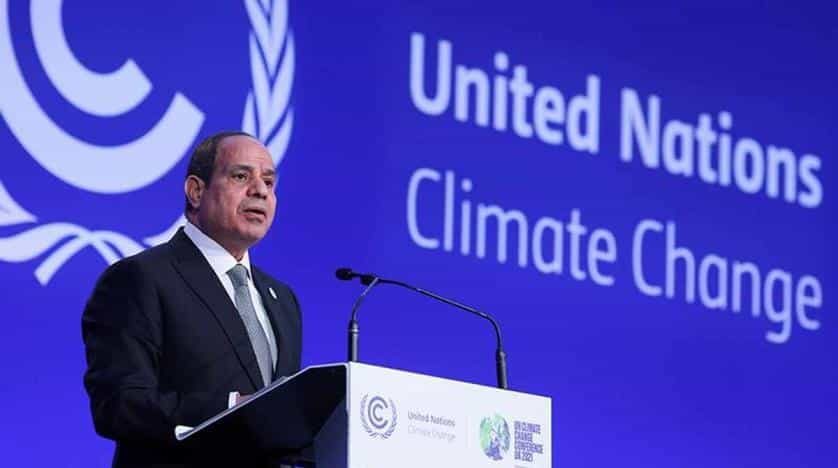

Ahead of COP27, which took place in the Egyptian city of Sharm El Sheikh, president Abdel Fatah al-Sisi said that his country would use its position as host to promote the interests of other developing nations, particularly those in Africa. Despite making up a small portion of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions, developing countries are among the hardest hit due to climate change’s worsening effects on issues like food insecurity, water scarcity, and extreme heat.

President Abdel Fattah Al-Sisi at COP26 in Glasgow | Photo Credit: Asharq Al-Aswat

Building on a diplomatic effort to seek African support in a dispute with Ethiopia over a project on the Blue Nile that Cairo views as a danger to its water supplies, Egypt is positioning itself as a champion of Africa and the Global South. But to reach its climate goals and reach the four-fold increase in the contribution of renewables to its power mix by 2030 by scaling up solar and wind projects as well as green hydrogen power, the country will need an additional US$246 billion in funding.

Given the low visibility of ecology and the limitations on civic action, some Egyptians express astonishment that the government would sponsor such a meeting. However, according to Rabab el-Mahdi, director of the Alternative Solutions Research project at the American University in Cairo, hosting COP27 “forced the government and consequently brought to society a broader discussion about climate change that has been missing from the overall national debate.”

What Is Egypt Doing About Climate Change?

Over the past two decades, Egypt has made significant strives in mitigating climate change, including doubling its wind energy production. In order to deal with the rising water stress, the country has also explored adaptation activities, such as building desalination plants and infrastructure for flood control. It was the first government in the Middle East and North Africa to issue green bonds, allocating $750 million towards sustainable water management and clean public transportation. Since accepting the role of COP27 host roughly a year ago, Egypt has unveiled a variety of climate-related initiatives, including plans to turn the popular tourist destination Sharm el-Sheikh into a “green city”.

Ambassador Wael Aboulmagd and Yasmine Fouad, Minister of Environment, Egypt. Photo by: UNclimatechange / Flickr

However, independent climate watchdogs like the Climate Change Performance Index and the Climate Action Tracker criticise the nation’s overall climate strategy as being vague and unambitious. Natural gas and other fossil fuels, which made up about 90% of the country’s capacity for power generation in 2019, contribute to the issue. Cairo, which is among the lower-income cities that claim they should be able to use fossil fuels to expand their economies until they can afford to switch to sustainable energy, wants to enhance the nation’s production of oil and natural gas.

Egypt’s lack of enthusiasm for reducing emissions has also drawn some criticism. Cairo updated its nationally determined contribution (NDC) – a country’s voluntary strategy for cutting its own emissions – more than a year after the Paris Agreement deadline. In addition to being dependent on outside assistance, Egypt’s new NDC lacks a specific goal for attaining net-zero emissions, like many other nations. Furthermore, Cairo also places more of an emphasis on adaptation rather than emission reduction in its 2022 National Climate Change Strategy.

Human Rights Violation

While the massive conference is being held in a Red Sea resort town with five-star hotels and soft, sandy beaches, human rights organisations and activists have accused Egypt of greenwashing – the practice of making claims about being environmentally friendly in order to boost one’s reputation. They have urged world leaders in attendance at the COP27 conference to address the Egyptian government about alleged violations of human rights, notably how it handles political detainees.

Protesters in Cairo, Egypt. Photo by Kuni Takahashi/Getty Images

In a recent report, Human Rights Watch (HRW) accused the Egyptian government of “severely restricting” environmental groups’ capacity to carry out their work through intimidation, harassment, and arrests, which led some activists to leave the nation. Other environmental advocacy organisations expressed concern over the Egyptian government’s tight control over planned protests and restrictions on the number of civil society organisations that were permitted to attend COP27. These restrictions have left only a small number of demonstrations permitted in a cordoned-off area of the conference.

Fears Over Future COPs

The oil and gas sectors receive two-thirds of all foreign investment in Egypt. Additionally, China is taking part in numerous large-scale infrastructure projects in the nation, while Russia is funding the El-Dabaa nuclear power station, whose construction will start later this year. Since some of the major emitters are also some of the nations Egypt maintains close ties with, the African country has been accused of doubling down on fossil fuels by stifling dissent.

Another concern about the influence of fossil fuel producers on international climate talks is growing among climate experts and activists as the United Arab Emirates, one of the largest oil exporters in the world. The UAE will preside over the next round of COP28 UN climate talks that starts in late November next year. Oil and gas, which make up around 30% of the the country’s GDP, also account for about 13% of the nation’s exports. The building and transport sectors, among many others, are likewise financially dependent on fossil fuels. At least 636 pro-fossil fuel lobbyists attended the COP27 discussions in Egypt, and 70 of them had ties to oil and gas businesses in the UAE.

The UAE president, Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan, speaking at Cop27 in Sharm el-Sheikh. Photo by: Sean Gallup/Getty Images

Russia and UAE have close ties, which is another cause for worry. Russia, a major producer of oil and gas, ranks fourth in the world for greenhouse gas emissions, and its gas production facilities are a significant source of the potent greenhouse gas methane. Since Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine in February, there has been a constant influx of Russian funds into the UAE, including partnerships in the energy sector and an increase in the importation of Russian oil so that the UAE may sell more of its own.

Featured image: Yasmine Fouad, environment minister for Egypt. Photo by IISD/ENB

You might also like: Did COP27 Succeed or Fail?