2020 marks the five-year anniversary of the signing of the Paris Agreement. Despite the COVID-19 pandemic delaying the United Nations’ 26th annual climate conference (COP26) until November 2021, world leaders from over 70 countries gathered virtually on December 12th to celebrate the event. As of December 2020, 127 nations, responsible for 63% of global emissions, are discussing or have pledged to bring their emissions to net zero within a specified timeframe. Nations acknowledging their ambitions and announcing these pledges are important steps, although mean little in terms of direct action towards mitigating climate change. Over the past five years, countries have begun to be held accountable for emission rates. Which countries have demonstrated strong and tangible progress, and which have failed to do so?

—

Considering the numerous net-zero commitments that have emerged over the last few months of 2020, and remaining optimistic that these pledges will be honoured, the Climate Action Tracker (CAT) group has estimated a best-case scenario of 2.1°C temperature rise above pre-industrial levels by 2100.

These projections indicate a markedly better trajectory for the world relative to five years ago, however they still fall short of the Paris Agreement’s goal of keeping temperature rise “well below” 2°C, and ideally below 1.5°C. The December 12 event concluded with a frank statement by Alok Sharma, British Minister for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy: “Friends, we must be honest with ourselves […]. As encouraging as all this ambition is, it is not enough.”

Much will depend on the actions of the world’s current leading emitters, including China, the US, the EU, India and Russia. While most of these countries have announced ambitious plans to reduce emissions and be carbon neutral by mid-century, a lack of tangible action and short-term targets may hinder their legitimacy.

You might also like: What Is The Paris Climate Agreement?

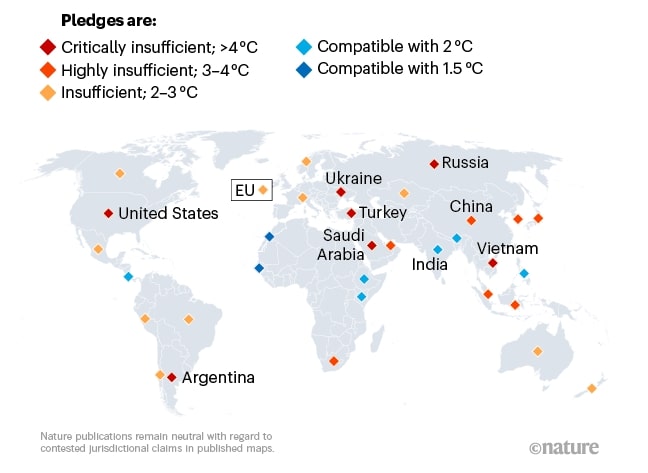

Fig. 1: Compatibility of individual countries’ current emission rates with Paris Agreement targets in 2020; Nature.com, sourced from Climate Action Tracker.

Meeting Targets

Overall, few countries are making progress towards meeting the Paris Agreement’s more ambitious goal of keeping temperature rise below 1.5°C. However, some major actors have performed commendably well in adhering to the agreement’s general targets. India’s emissions, for instance, are rated by the CAT as being compatible with the 2°C goal, meaning that while India’s emissions continue to increase, they are diminishing at a rate in line with the goal. As the world’s fourth-largest emitter of greenhouse gases, India’s climate-related actions carry significant weight.

India’s investments in renewable energy projects recently outpaced funding for fossil fuels. The country has been making rapid progress in expanding its renewable energy sector and could meet its 2030 target to rely on renewables for 40% of its energy mix early. Much will depend on whether India can decouple itself from fossil fuels in the short term and abandon plans to build new coal-powered plants.

Another entity that has performed reasonably well is the EU, whose financial capacity allows it to set ambitious targets. The bloc is not only on track to meeting its original Paris goals of a 40% reduction in emissions by 2030, but it has also recently announced an increased goal of a 55% reduction. This is an important development, as the EU’s original targets were widely seen as unambitious given its wealth.

As the world’s third-largest CO2 emitter, the EU was always going to face difficulties in reducing its carbon intensity output. The EU as a whole, as well as many of its constituent countries, has invested extensively in developing a cross-sectoral green economy, notably addressing energy, transportation and agriculture.

A Promising Future for China

Meanwhile, China continues to position itself as a global leader in climate policy, showing tentative promise for a sustainable future. Prior to 2020, China’s Paris Agreement goals were widely seen as unambitious and inadequate. However, recent developments and announcements have changed the country’s outlook. The country exists as a unique case within the discussion on global emissions. It is the world’s highest emitter, and a distinct urban/rural divide, regional inequality and ongoing development in many areas of China mean that the country has yet to reach peak emissions and will continue to invest in coal power over the coming years.

Despite these realities, China’s immense financial capacity and desire to be a leader in the tech world has driven the country to invest substantial sums to develop a greener economy. In 2018, more electric cars were purchased in China than in the rest of the world combined, and the country has heavily subsidised the growth of the electric vehicle industry. Despite being the largest consumer of coal, China is also the largest producer of renewable energy. If China is able to implement its national carbon trading scheme over the next five years, it would be home to the world’s single largest carbon trading market. China, which has traditionally been a controlled economy, has also shown increased willingness to ride the green wave of market forces to organically achieve decarbonisation.

China has announced or reiterated ambitious climate targets, including pledging to achieve carbon neutrality by 2060 and to reach peak emissions by 2030. The bravado displayed by President Xi Jinping in his remarks is commendable, although China will need to continue taking decisive action to match its ambitious rhetoric.

Insufficient Efforts

Conversely, some of the world’s largest emitters are doing woefully little to meet both individual and collective Paris Agreement targets. Russia, for instance, is the world’s fifth-largest emitter, and has expressed little to no interest in decoupling itself from fossil fuels and minimising its carbon footprint. The country is not on track to meet its unambitious Paris target to reduce emission rates by 25-30% by 2030, and has not announced any long-term strategy. Russia has notoriously dragged its feet on climate policy implementation, only ratifying the Paris Agreement in 2019.

In addition to not being on track to meet its 2030 targets, Russia has expanded its reliance on fossil fuels, particularly natural gas, while actively limiting the growth of a renewable energy market. The country has also hindered international climate action policy, vehemently opposing the EU’s efforts to implement a carbon border tax. Despite witnessing first-hand the warming effects of climate change on the Arctic, Russia has opted to focus on the economic opportunities of these impacts by staking claims to newly-emerged navigational routes in the Arctic and expanding agricultural production further north.

The country has announced tentative legislation that would allow for increased control over CO2 emissions and a carbon market, however any meaningful legislative action is unlikely to occur soon. Before next year’s convention, Russia will need to be pressured to update their intended contributions and establish higher targets. Unilateral action against Russia, such as the EU’s carbon border tax, could play an important role in motivating the country to decouple itself from fossil fuels.

Another serious offender that has delayed necessary implementation of ambitious climate policy is the US. As the world’s second-largest contributor to CO2 emissions, a strong climate policy on behalf of the US would be a significant step towards achieving net-zero emissions. The country’s original Paris goal was to reduce emissions by 26-28% by 2025. Despite only formally leaving the agreement in November 2020, the Trump administration has actively rolled back climate-related measures and has given firms liberties to operate free of environmental regulations.

The CAT has rated the US’s performance as ‘critically insufficient.’ While President-elect Joe Biden is set to shift the landscape of climate policy substantially, ample damage has already been done over the past five years. The Biden administration plans to rejoin the Paris Agreement ‘on day one,’ and announce a new 2030 target and while a Biden presidency may be able to reverse some of the former administration’s actions, partisan resistance in the politically polarised country may present obstacles to realising more ambitious goals.

Changing Dynamics

2020 has proven to be a landmark year not only for new net-zero pledges, but also for investments in developing green economies to recover from the COVID-19 pandemic. Many nations have seen the pandemic as an opening to redirect government spending towards expanding their capacity for renewable energy and creating new low-carbon jobs.

Around 30% of the EU’s $750 billion stimulus package directly addresses environmentally sustainable projects. France has developed its own stimulus plan, of which one third is to be allocated towards green measures, totalling around €30 billion. Germany has also negotiated a package worth €50 billion to transition towards a greener economy and continued research and development of new technologies. Meanwhile, South Korea has announced its own Green New Deal as part of its economic recovery plan, while New Zealand is expected to place climate change at the centre of its recovery plans. Many more countries are expected to ramp up green investments in the months ahead.

Some countries remain statically opposed to green initiatives within the context of recovery plans. India seems to be inviting private investments to support the country’s coal industry, despite the falling costs of renewables. Russia remains unyielding to renewable energy and low-carbon alternatives in its own recovery plans, preferring to support the fossil fuel industry. In the US, it is unclear how much ambitious legislation the incoming administration will be able to push through a potentially divided legislative branch, despite President-elect Biden’s economic recovery plan calling for significant investments into green initiatives.

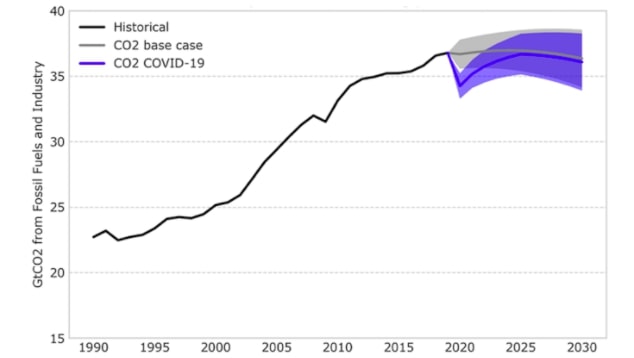

Given the drop in CO2 emissions in 2020 due to the pandemic, global investments towards developing green economies and numerous net-zero pledges, it is possible that greenhouse gas emissions have already reached their peak. While past predictions placed peak global emissions in the mid-2020s, current trends indicate that overall, emissions may never return to 2019 levels even as economies begin to recover.

Fig. 2: Historical, CO2 base and CO2 allowing for COVID-19 carbon intensity trends with uncertainty range; The Breakthrough Institute; 2020.

Best-case scenarios accounting for current trends indicate that the Paris Agreement’s goal to keep warming at 2°C by 2100 may be achievable, if just barely. However, it appears that the opportunity to meet the ambitious target of keeping temperature rise below 1.5°C has passed. This failure will have its consequences, particularly on developing countries. The Paris Agreement appears to have provided the necessary momentum to shift nations’ focus towards low-carbon alternatives, although the lack of a functional policing mechanism may have doomed the more ambitious targets from the start.

The mid-century net-zero pledges coming from many countries this year are commendable, although countries will need to be held accountable for their actions over the short term. More ambitious and actionable 2025-2030 targets need to be set and announced over the next year.

Much will become clearer over the next few months. The delayed climate conference gives major emitters such as the US and China more time to clarify their climate policy. As countries worldwide continue to evaluate how to implement green initiatives in recovery plans, it is probable that more ambitious targets for emission reductions could be made by or at COP26 next November.