Why this Metric

Air and water are the quintessential elements to life on Earth. Yet today, over 90% of the population breathes unsafe levels of pollutants, and four billion people experience severe water scarcity for at least one month a year. Of these four billion, 1 billion live in India and another 0.9 billion in China.

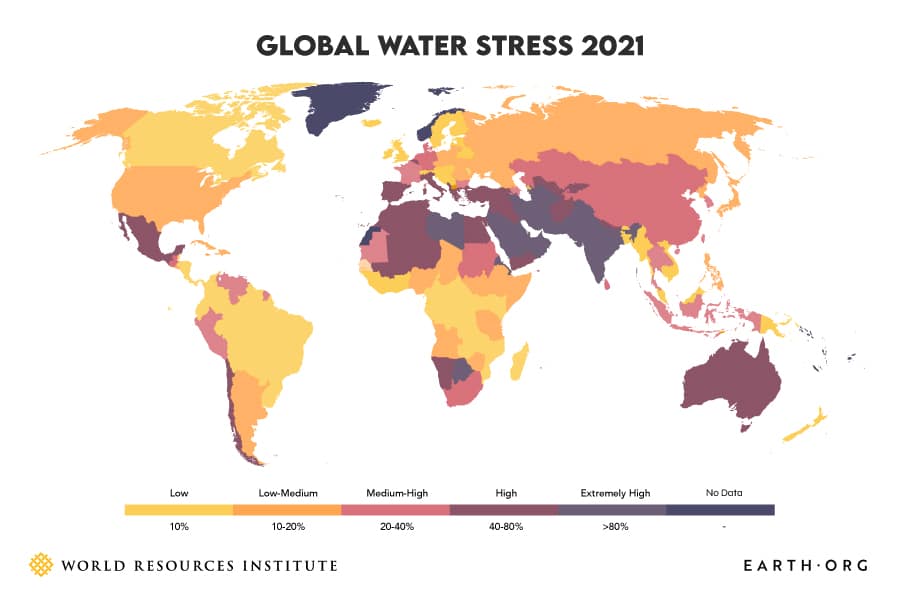

Major cities around the world, like Cape Town, Beijing or Chennai have faced “Day Zero”, the day the tap runs dry. 17 countries, home to a quarter of the world’s population, face “extreme water stress”, according to the World Resources Institute’s (WRI) Aqueduct Water Risk Atlas, whose data we have mapped above.

Exploring the Metric

Water is essential for food production, electricity generation, manufacturing, and many other cogs of human society. What does water stress look like? In large cities, its residents standing in line for hours to get water from government tanks, and covid-reminiscent shutdowns of many commercial activities.

In unstable regions like that of the Sahel (the southern border of the Sahara), water stress can lead to, and exacerbate food insecurity and conflict. In Somalia for example, drought forced rural communities to sell off more livestock than usual, leading to a drop in prices and plummeting rural incomes. Poverty incentivizes illicit activities and extremism, which fuelled the rise of terrorist groups like Al Shabaab whose fighters are offered cash revenue.

In addition to drought, many draw water from untreated, dangerous sources that put them and their children at risk of disease. The World Health Organization estimates that ~3.6 million people, 2.2 million of which are children, die from water-related disease each year.

Where the Numbers Come From

The WRI’s Aqueduct tool was built off a number of data sources, including academic papers, WHO reports, hydrological modelling and remotely sensed (satellite) information.

It is all compiled into a set of freely available resources, including the Aqueduct Water Risk Atlas, Aqueduct Food, Aqueduct Floods, and Aqueduct Country Rankings, designed for decision makers, private entities and the general public.

Future Outlook

Higher temperatures widely modify the Planet’s water cycle, especially in the atmosphere. For every 1°C it warms, its water-carrying capacity increases by 7% (according to the Clausius-Clapeyron relation). The current consensus is that this will make droughts drier, floods wetter and both more frequent.

UNICEF reports that some 700 million people could be displaced by intense water scarcity by 2030, projecting it to be one of the main drivers of future climate migration. Farmers in Honduras and Guatemala are already mass migrating north to escape crop-killing droughts, hurricanes and hunger.

With the world tilting toward protectionism and closed borders, these people are unlikely to be given safe haven, meaning they’ll end up in massive refugee camps where they’ll remain exposed to the elements, hunger and disease.

Water filtration technologies are improving and becoming more accessible, providing a small amount of relief. If developed countries start honoring their climate funding promise, those at risk could make some headway on better infrastructure and water stewardship. This issue will come down to international help and whether we start thinking as a global community.

This article was written by Owen Mulhern.

Check out our other indices here.

![The Statistics of Biodiversity Loss [2020 WWF Report]](https://u4d2z7k9.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/lprwinkyTHB-544x306.jpg)