A comprehensive report on the state of the world’s coral reefs was recently released, so we at Earth.Org mapped it out to give you a lay of the land.

—

The Global Coral Reef Monitoring Network (GCRMN), established in 1995, has undertaken the task of informing the world on the state of its coral reefs.

To say these ecosystems are invaluable is far from an overstatement – despite covering only 2% of the ocean area, they house 25% of its species. Naturally, many human societies have settled around these bountiful areas, which also protect coasts from erosion and slow storm surges.

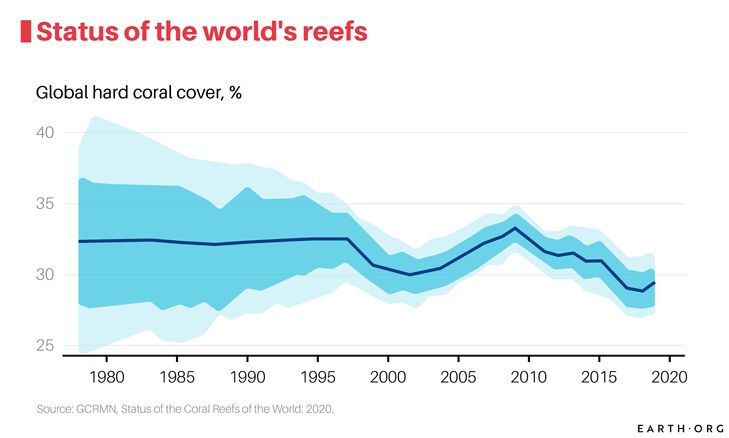

They are now under significant pressure from human activities, and though they show resilience, how much exactly remains to be seen. The GCRMN’s latest report, published in September 2021, reaches as far back as 1978 to better understand how corals are reacting to human pressure.

At first high and stable, a mass bleaching event occurred in 1998, decreasing global hard coral cover by 32.5%. Corals recovered to a very healthy level by 2009, but respite was short-lived because 8 years of decline ensued, with a slight upward tick to cap off a decade of loss by 2019.

Some of the most damaging practices to vibrant ocean-floor ecosystems is direct bludgeoning by coastal development, dredging, quarrying, and bottom trawling. This last one consists in dragging multi-ton blocks along, which pull a huge net behind them. As you can imagine, the technique is frighteningly effective, yielding more catch by weight than any other method each year.

Regulation and enforcement is a simple solution for the above, but a range of other issues plague our reefs. Pathogens and toxins from poorly recycled sewage water inexorably accumulate in the ocean and poison coastal lifeforms first, while micro-plastics and other forms of trash have become pervasive on our planet.

Acts as simple as overfishing can be too much for a reef’s ecosystem to bear, increasing its vulnerability and chance of collapse.

Policy-makers need a lay of the land if they are to take effective action, and this is where the GCRMN’s hard-gathered data comes in.

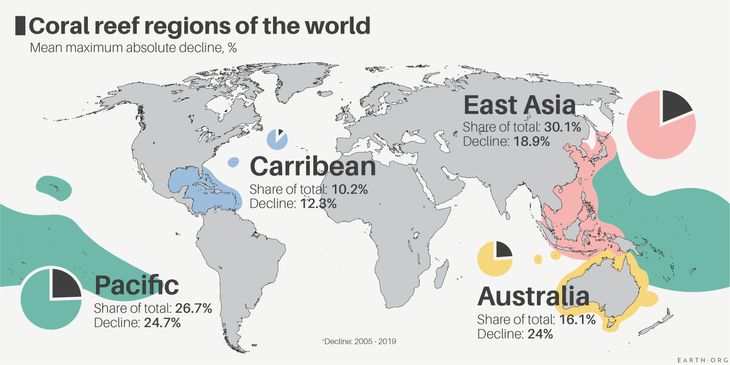

We’ve highlighted the 5 most coral-rich regions of the world, which contain over 80% of the total, along with the losses they’ve sustained overall.

The optimists among you may have noticed that coral reefs can regenerate – a fortunate and encouraging fact. However, the GCRMN’s survey found that within 8 of 10 regions, some corals were never fully able to recover, suggesting an imminent limit to reef resilience.

It is incumbent on few rather than many to legislate for coral protection. However, this is less likely to happen in developing countries where short-term priorities trump the long-term.

This article was written by Owen Mulhern.

You might also like: Climate Change is Shifting Crops

![The Statistics of Biodiversity Loss [2020 WWF Report]](https://u4d2z7k9.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/lprwinkyTHB-544x306.jpg)