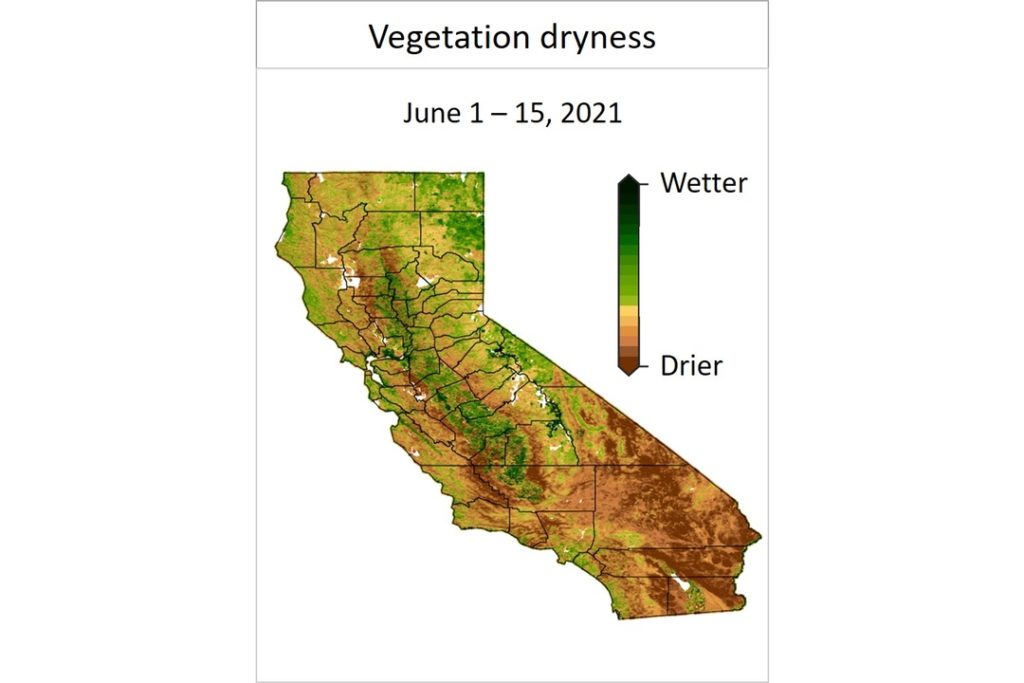

It is unclear how the drought that most of California is facing will affect wildfires in 2021. Using the latest satellite observations, scientists estimate that two-thirds of the state’s vegetation is drier than normal, resulting in high wildfire hazard.

—

This is a guest article, more about the authors in the footer.

Memories from the 2020 wildfires are burned into Californians’ minds. As residents woke up to orange skies laden with smoke, wildfires grew to extraordinary sizes. Among the six largest wildfires in California’s history, five occurred in 2020. Even beyond California, 2020 was a record-setting year. Wildfires burned over 10 million acres (1/10th the area of California) – three times the previous record – blanketing the West in smoke for weeks. As communities continue to recover from the aftermath of wildfires, a question looms- what will 2021’s wildfires look like?

Precipitation since last year has been dangerously low, and the snow that did accumulate in the mountains – which normally provides water to ecosystems during the warm spring and summer months – melted at record pace this spring, leaving California essentially without this critical resource as it enters the hottest part of the year. As of June 22, 2021, 85% of the state was in the two most severe drought categories , with more than a third now experiencing “exceptional drought”, according to the US Drought Monitor.

Dry vegetation provides fuel for forest fires. One of the major causes for last year’s wildfire intensity was both the amount and dryness of fuels. Now, elevated temperatures and low winter-time precipitation has left California’s vegetation primed for wildfires this year.

Sensing vegetation dryness from space

Vegetation dryness for the first half of June 2021. Vegetation dryness is referred to as “Live fuel moisture content” by fire scientists. Vegetation dryness estimates are not available for areas that burned in 2020 due to limitations with our estimation technique.

Historically, it has been difficult to assess vegetation dryness using only water availability and temperature because other things come into play, like depth of roots of plants. Thankfully, modern satellites allow us to observe vegetation dryness directly.

The map above shows our estimate of vegetation dryness using state-of-the-art satellites from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and the European Space Agency (ESA), and artificial intelligence. Akin to using X-ray to see what’s inside our body, we use very low power microwave radars to scan vegetation for their water content. Our system first learns to estimate vegetation dryness using ground-truth measurements collected by the US Forest Service. It then tracks small changes in microwave reflectance and vegetation color to estimate vegetation dryness. If you are interested in exploring vegetation dryness further, visit our interactive web-app updated biweekly. The app displays vegetation dryness for the entire western US since 2016 and is updated biweekly.

An abundance of dry vegetation

Vegetation dryness in the first half of June 2021 compared to the corresponding period in 2020 (left) and the average of the corresponding periods in 2016 – 2020 (right). Red colors indicate that 2021 is drier than the periods it’s being compared to.

About 65% of the state’s vegetation was drier in the first half of June 2021 than in the same period a year ago (left panel above) with the southern regions, home to Los Angeles, in the most critical state. Even a small decline in vegetation dryness can increase wildfire hazard significantly because the tendency for vegetation to ignite increases suddenly below certain dryness thresholds. Hand-drawn maps from experts at the US Drought Monitor also indicate extremely dry conditions across much of California priming it for a harsh spate of wildfires in 2021.

Regions in San Benito, Monterey, San Luis Obispo, Santa Barbara counties and much of the Central Valley had vegetation wetter in the first half of June 2021 compared to the average for the same period in the previous five years (2016 – 2020). This is shown in the right panel of the above figure. Nevertheless, even if they are wetter than in previous years, wildfire hazards can still exist in these places if the vegetation dryness remains below ignition threshold.

Does this mean the California wildfires will be large in 2021 too?

We don’t know.

2020 was an unusually catastrophic year for wildfires, not just because of the vegetation being dry, but because of at least two other factors. First, a very rare lightning storm occurred in August when humid air from the tropical storm Fausto came up the coast. Second, two intense heat waves set daily temperature records all over the west coast, the first of which preceded – and likely contributed to – the lightning storms, and the second of which occurred around the Labor Day holiday. While this spring and early summer are again setting temperature records in the state, the exact conditions that occurred in 2020 were quite rare.

Further, even though vegetation dryness is a key indicator of wildfire hazard, it is not the sole determinant. Wildfires are also affected by other factors such as when and where ignition sparks occur, weather conditions at the time of the fire (such as wind speeds), how much vegetation and litter is present, and more. Thus, having very dry vegetation does not alone ensure that there will be bigger wildfires, and the maps presented above should only be viewed as an indicator of greater risk.

Whether or not fires are as severe in 2021 as they were in 2020, it is clear that there is a lot of dry vegetation. The good news is that there are many preventive steps we all can take to prevent accidentally igniting wildfires, and harden our homes to mitigate the impact of wildfires. Taking preventative steps now can help to lessen the odds that this very dry start turns into the kind of widespread catastrophe that is quickly becoming an all-too-familiar feature of life in the Golden State.

About the authors

Krishna Rao, Noah S. Diffenbaugh, and Alexandra G. Konings are at Stanford University, Marta Yebra is at Australian National University, and A. Park Williams is at University of California, Los Angeles.

You might also like: Majority of Ocean Plastic from Takeout, Study Finds

![The Statistics of Biodiversity Loss [2020 WWF Report]](https://u4d2z7k9.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/lprwinkyTHB-544x306.jpg)