New research has shown that early humans were far more widespread than previously thought, urging a re-definition of our historical relationship with nature and biodiversity. The evidence suggests that humans are not implicitly harmful to the natural environment, and rather it is the intensification of land use that has induced the current crisis.

—

A new study from an international team of archeologists, ecologists and geographers suggests that the key to solving the present environmental crisis is to look to indigenous practices that fostered sustainable biodiversity for over 12,000 years.

This new research shows that for the last 12 millenia, people have inhabited a much larger proportion of the earth’s terrestrial land than previously thought, all while managing it responsibly and sustainably.

Using the most up-to-date reconstruction tools of historical human population and land use better understand the timeline and geography of human expansion, and thus characterize humanity’s historical relationship with nature. The results of the reconstruction are in line with contemporary global assessments: 80% of the earth’s land surface has been transformed by human activity, with 51% classified as ‘Intensive’ and 30% as ‘cultured’, while only 19% is wildland. However, historical observations were widely different from prior historical reconstructions, in which Wildlands covered 82% of land surface in 6,000 before CE. They report: “even 12,000 years ago, nearly three-quarters of terrestrial nature was inhabited, used and shaped by people,” suggesting it is more than mere human presence that harms biodiversity.

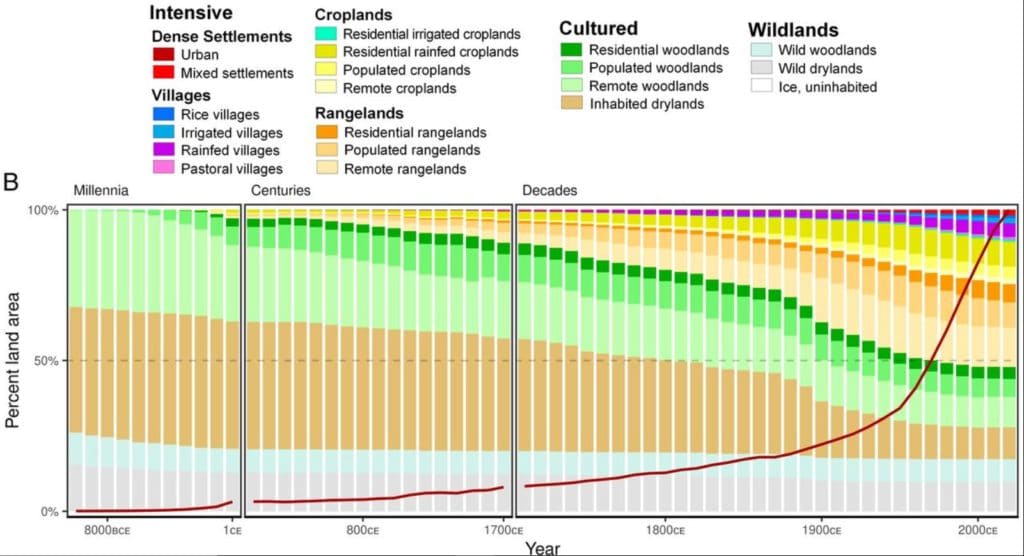

Indeed, a lingering paradigm in anthropological and natural sciences is that human colonization of wildlands is inherently damaging, and that the bulk of it is relatively recent. The findings described of this study challenge that paradigm, suggesting that humans are perfectly able to live in harmony with their surroundings, and even help biodiversity thrive. In the graph, you will see three main categories: wildlands, uninhabited by humans; cultured, inhabited with less than 20% intensive land use; and intensive, with over 20% intensive land use.

Global changes in anthromes and populations 10,000 BCE to 2017 CE. (B) Global changes in anthrome areas, with population changes indicated by red line. Anthromes are classified using population densities and dominant intensive land use. Source: Ellis et al. 2021.

We see that cultured land, in green and brown, comprised most of the inhabitable land during the last era (Holocene). From around 1700 common era (CE) onward, intensive land began its exponential rise into the present day, and does so entirely at the expense of cultured land.

You’ll notice the acceleration is concurrent with that of the human population curve in red, although not quite as drastic.

Orange grabs the eye in the latter part of the timeline, carving out a large space for itself and hardly slowing – these are cattle grazing lands. Without getting into a debate over whether we should be eating meat, it is a lot of our planet’s available space and resources to give to a single thing, especially one that can be lived without.

Moving on, the analysis revealed another interesting point: earlier humans may have actually helped biodiversity thrive, increasing species richness in their environment. However, the positive effect seems to disappear after 1500 CE, indicating a shift in our relationship with nature after European colonial expansion. Based on the conclusion that intensive land use leads to biodiversity loss, this could mean that the Europeans’ technology transfer to many less developed areas of the world might be the cause.

Of course, we couldn’t roll back global development to a pre-industrial or even pre-agricultural lifestyle even if we wanted to, so what is the takeaway? The most obvious one is how beneficial indigenous land protection can be, as it turns out that humans ready and willing to live outside of the globalized, urbanized world actually do more good than harm to the planet.

The second is that the amount of uninhabited land has been very stable throughout the Holocene, meaning there is a good reason humans never occupied those areas. We therefore colonized all the desirable land very fast, and since then have only been changing the way we exploit it for the worst, mostly to accommodate our exponential population growth. Since this is expected to continue until 2064, when we are expected to hit 9.7 billion. Growing energy, food and living area demand will chew through a lot of the remaining space if we don’t rethink our land usage portfolio, and no more biodiversity is very bad news.

The authors said: “Efforts to achieve ambitious global conservation and restoration agendas will not succeed without more explicitly recognizing, embracing, and restoring these deep cultural and societal connections with the biodiversity they aim to sustain.” We’ve long known how to nurture our environment, but the knowledge was put aside for profit and, in some cases, unnecessary development. We have more than we need; poor distribution of the resources is humanity’s next problem to solve.

This article was written by Lola Robinson and Owen Mulhern. Cover photo by Stéfano Girardelli on Unsplash.

You might also like: Melbourne Air Pollution

References:

-

Erle C. Ellis, Nicolas Gauthier, Kees Klein Goldewijk, Rebecca Bliege Bird, Nicole Boivin, Sandra Díaz, Dorian Q. Fuller, Jacquelyn L. Gill, Jed O. Kaplan, Naomi Kingston, Harvey Locke, Crystal N. H. McMichael, Darren Ranco, Torben C. Rick, M. Rebecca Shaw, Lucas Stephens, Jens-Christian Svenning, James E. M. Watson. People have shaped most of terrestrial nature for at least 12,000 years. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2021; 118 (17): e2023483118 DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2023483118

![The Statistics of Biodiversity Loss [2020 WWF Report]](https://u4d2z7k9.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/lprwinkyTHB-544x306.jpg)