A new study published last month shows in great detail how the Antarctic ice shelves could recede as global warming continues. The warming scenario we choose to experience in the next few years will determine how much of it remains intact.

—

Researchers have been studying and modeling how Antarctica might fare against climate change for decades now but forecasts have been limited in detail. This new study, from scientists at the University of Reading and the University of Liège in Belgium, shows how the ice shelves lining the Antarctic coast may melt away under different degrees of global warming.

An important thing to understand is that all the ice we see in polar region photographs is not the same. There are glaciers, ice sheets, ice shelves, icebergs, and sea ice, all different in form and behavior.

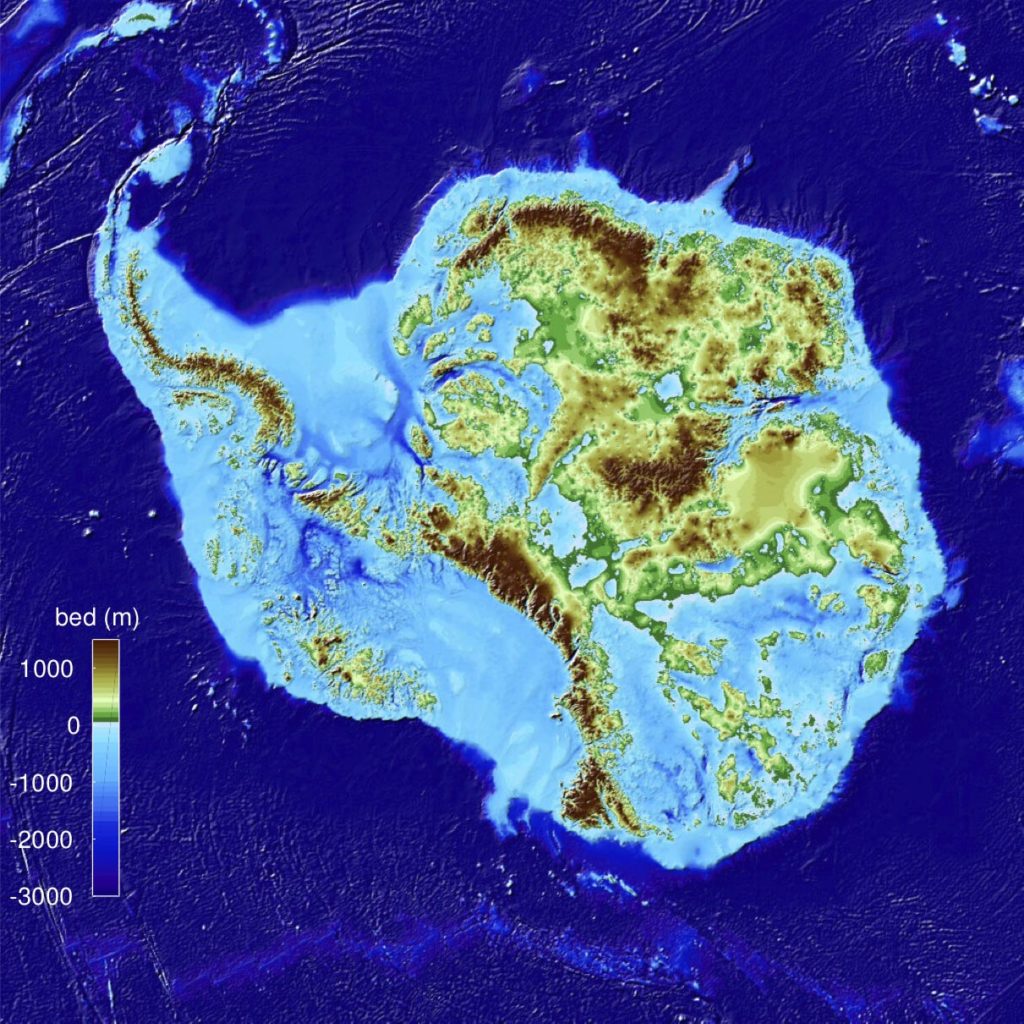

The researchers here focused on ice shelves, floating platforms of freshwater ice that slide off the landmass onto the ocean and remain frozen on the cold waters, often looking like part of the continent itself. (Antarctica on a map would look very different if its ice shelves weren’t included.)

Source: Mathieu Morlighem, UCI

When ice shelves melt or break into pieces and float away they allow glaciers and ice sheets, both of which sit on land, to move into the ocean at a faster pace. The shelves essentially act like bottlenecks to keep ice and meltwater from flowing too fast, by bumping into them or helping re-freeze the water. The process keeps ice loss at a rate that is normally balanced by the accumulation of more land ice through the buildup of snow.

It’s this accelerated movement from glaciers and ice sheets that causes concern, as this would directly cause sea levels to rise (the melting ice shelves themselves don’t raise sea levels as they were already floating on the water).

Some research has estimated that without ice shelves, the glaciers they used to block may move towards the ocean up to five times faster.

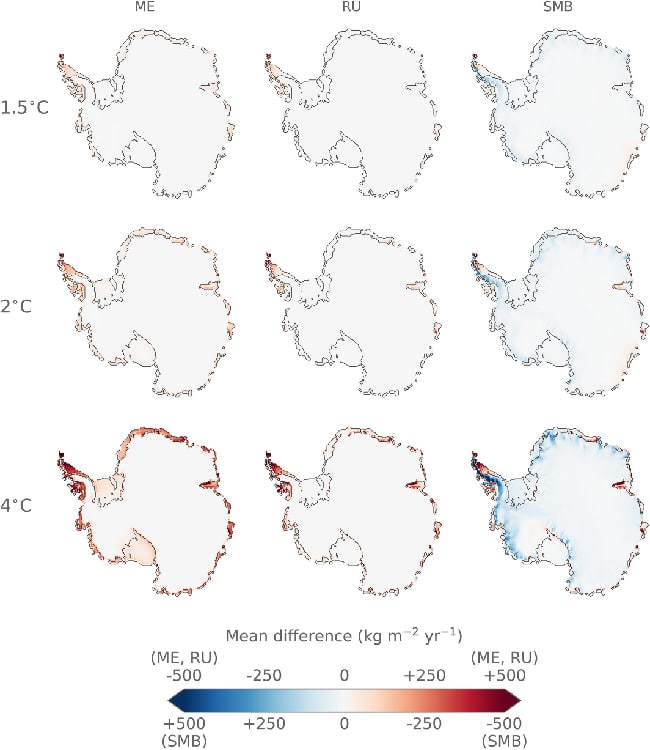

This study found that if current global warming continues until we’re at 4°C above pre-industrial levels, more than a third of Antarctica’s ice shelves could disintegrate. That’s 190,000 square miles of ice, about two times the size of the United Kingdom. If warming can be halted at 2°C, the increasingly difficult target of the 2015 Paris Agreement, only half as much would be vulnerable.

Many of Antarctica’s ice shelves are on its Western side, such as on the Antarctic Peninsula that points up towards South America. Out of the four ice shelves identified as most at-risk, three are in that region: Larsen C, Wilkins, and Pine Island (just south of Abbott); the Shackleton ice shelf on the east coast is the fourth.

Source: Ted Scambos, NSIDC

The study modeled meltwater, runoff, and surface mass balance (a measure of total ice) under warming scenarios of 1.5°C, 2°C, and 4°C. In the visualization below, red indicates increases in meltwater and runoff and decreases in surface mass balance (note the legend).

Source: Gilbert and Kittel, Geophysical Research Letters, 2021

The study also explained how exactly ice shelves melt to the point of collapse. It’s a process termed ‘hydrofracturing’ whereby excessive, pooled meltwater on the shelf’s surface moves in between cracks in the ice and weakens it. In cooler temperatures that meltwater would refreeze or be so little that it mainly remains on the shelf’s top.

The Antarctic Peninsula is one of the fastest warming places on Earth, already on average 2.5°C warmer than what it was in 1950. In the past 30 years or so researchers have observed its ice shelves breaking apart at an unprecedented rate. In 2017 the Larsen C ice shelf made the news when it lost a piece the size of Delaware.

It all sounds bad, and it could be, but what’s key is that so much future ice melt will only happen if we let those warming scenarios happen.

Some climate scientists see a 3°C world as most probable now, more than the ideal 2°C but less than the potentially catastrophic 4°C. Time will tell how much studies like these, with their reason and forewarning, move our societies to act on global warming mitigation.

This article was written by Debbie Sanchez.

You might also like: Air Pollution in Shanghai

![The Statistics of Biodiversity Loss [2020 WWF Report]](https://u4d2z7k9.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/lprwinkyTHB-544x306.jpg)