The Maldives are a small archipelago in South Asia, located in the Indian Ocean 700 kilometres southwest of Sri Lanka and India. Around 80% of its land area is under 1 meter above sea level, meaning it will be one of the first nations to be entirely engulfed by the steadily swelling seas. NASA satellite imagery allows us to get a bird’s eye view at how the Maldives are adapting their islands to stave off sea level rise.

—

Sea level rise has massively accelerated over the past century, going from ~1.5 mm per year in 1900, to 4.8 mm per year today. With no signs of relent, one study predicts that low-lying islands will become uninhabitable by 2050 before full submersion, driven by frequent flooding and freshwater scarcity. If we expand our scope to the end of the century, things become more uncertain: low end estimates put sea level rise at half a meter, while the high end stands at 2 meters.

In the worst case scenario, the world’s coastal geography would undergo serious change, forcing us to massively invest in adaptation. The lower estimates still imply a necessary rethinking of where and how we live, with 680 million people living in low coastal areas and a US $6 trillion ocean-based economy.

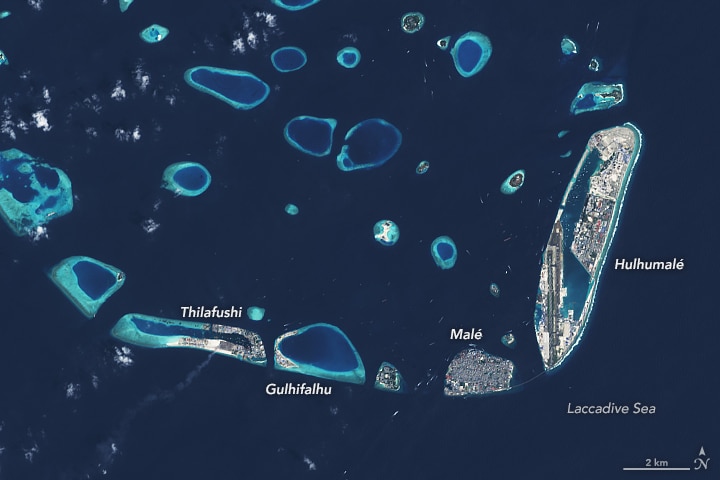

Facing forced displacement, the Maldives government is exploring plans to purchase safer land in other countries, but most of their efforts have been in enhancing resilience in their home-state. Hulhumalé is a newly constructed artificial island just northeast of the capital, Malé, built up by pumping sand from the sea floor. Officially inaugurated in 2004, it is 4 km2 in area and houses a population of 50,000, expected to grow to 200,000 in the upcoming years. Twice as high as Malé, it can provide refuge from both typhoons and the slow oceanic rise.

The Maldives, February 3, 1997. Iimaged by the NASA Earth Observatory’s Lauren Dauphin, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey.

The Maldives, February 19, 2020. Iimaged by the NASA Earth Observatory’s Lauren Dauphin, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey.

Hulhumalé is far from being the only Maldivian land reclamation project; Thilafushi is a lagoon to the west that has become a large landfill and a common location for trash fires (see the southwestern smoke plume in the 2020 image), and Gulhifalhuea houses another project meant to create space for manufacturing and industrial activity.

One thing to bear in mind is that islands like the Maldives are constantly being reshaped by ocean currents and sediments flux. Coastal erosion usually compounds sea level rise, enhancing land area loss. However, the Maldives’ healthy coral reef system provides a natural defence against erosion, and it has even been suggested that offshore sediments may be building up the archipelago.

Unfortunately, built up land can rarely benefit from these natural solutions as seawalls stop sediments from grafting more land area onto the island. Overall, it may have more time than initially predicted, but current sea level rise rates mean it will largely disappear within a century.

This article was written by Owen Mulhern.

You might also like: Shifting Baselines and the Elusiveness of Climate Change

![The Statistics of Biodiversity Loss [2020 WWF Report]](https://u4d2z7k9.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/lprwinkyTHB-544x306.jpg)