The world is well aware of its plastic problem, and viable solutions haven’t seem to have surfaced yet. Bioplastic sounds like something we could endorse, but what is it really?

Earth.Org takes a closer look.

—

You may recall a time recently when you picked up a plastic utensil and thought the texture was a little off or perhaps looked a little different than the one you remember being paired with that slice of birthday cake a few years ago. It’s a good chance that utensil was made of bioplastic. Bioplastics are derived from more naturally acquired ingredients with names we recognize and can usually pronounce like sugar cane, corn, potato, and other vegetable starches. This compared to conventional plastic which comes from a blend of petroleum and other various oil products according to the Energy Information Administration or EIA.

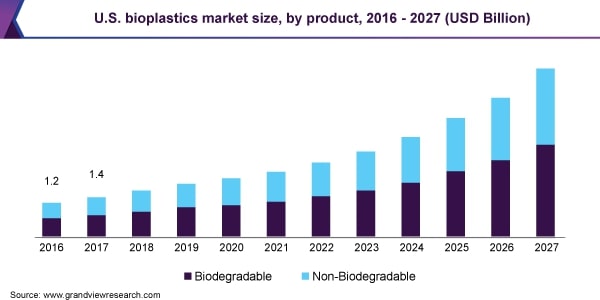

Bioplastics have been experiencing a rapid increase in demand. Even before COVID-19 all but forced the United States and much of the world back over to single-use materials as a health precaution; The bioplastics industry reported a market value of 8.3 billion dollars in 2019 and expects to grow by another 16.1% in the next 7 years according to the Grand View Researcher’s Market Analysis Report. That’s roughly the same market value as the NFL’s New England Patriots and the NBA’s Los Angeles Lakers market values combined. Bioplastics are in more than most of us realize. From more well-known products like the utensil mentioned earlier, plastic food wraps, to lesser-known items such as internal surgical tools like sutures according to an article out of MIT.

Conventional plastics come from feedstock; a pipeline of fossil fuels consisting of crude oil, and natural gas. The IEA admits they cannot accurately track the origin or amounts of each kind of petroleum and oil-based product that are siphoned into current plastic production. Bioplastics come from agricultural monocropping, traditionally cultivated with a high level of fertilizer. Agriculture dedicated to bioplastic production varies between sources; however, most estimates average the range to be in the 100,000s of hectares annually for the United States, and China significantly more. Fertilizer runoff, when crop soil becomes oversaturated with fertilizer. Those chemicals run off the surface of the land with irrigation and rainwater, and enter local tributaries, rivers, and eventually our oceans. According to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) This leads to harmful algae blooms, hypoxia or dead zones, acid rain, and air pollution.

Not all bioplastics are created equal. When many of us think “Bio” we think biodegradable, or compostable. When in fact not all bioplastics biodegrade. Petroleum products are made up of complex molecular strains that are hard if not near impossible to break down in nature leading to environmentally devastating microplastic. Bioplastics are designed to mimic conventional plastics down to the molecular structure, leaving only a small portion of bioplastics biodegradable. Another important aspect to consider is how long this degradation takes. In short, it depends. According to a ScienceDirect article in 2019, plastic bags can fully biodegrade in less than a year where utensils can take almost 6 years. Where the plastic ends up also changes the rate of decomposition. On average bioplastics break down faster in maritime environments compared to soil environments. Unfortunately, this still leaves plenty of time for bioplastics to make their way into our waterways and oceans. Rayon, a biodegradable bioplastic commonly found in clothing, and derived from cellulose was found to make up 58% of the overall microplastic extracted from ocean birds in a 2015 study conducted by the United Nations. Rayon is an example of how misleading the term bioplastic can be; a fact the fashion industry is keenly aware of. According to an article published by “EDGE”, a fashion information platform, rayon takes anywhere from 20-200 years to fully biodegrade. While better than conventional petroleum-based plastics which can take 1,000’s of years to fully breakdown, it’s a long way from ecologically ethical.

Source: NPR.

You may be wondering, “can it be recycled?”

It’s true some conventional plastics can be recycled. However, that number is far more limited than many of us realize. There has been a serious lobby on behalf of the industry to include that little recycling triangle on nearly every type of plastic even if it’s nearly impossible to recycle that product according to NPR and Eco-Watch.

Source: Boredom Therapy.

In reality, America recycles less than 10% of its plastic. Bioplastic actually actively works against this already small percentage. Many of us blindly throw plastic into our bins with the best of intentions or leave it to the recycling factory to sort it out at the plant. However, on such a large scale it’s impossible to separate every type of plastic. Bioplastics end up being one of the worst contaminators of recycling because so few programs recycle it due to the lack of economic viability.

Bioplastics, while a novel, are far from ideal. It’s important as consumers that we be aware of the real impact bioplastics have on our environment. Actions are too often curbed by assumptions, but it is our responsibility to educate ourselves and not become complacent.

As for ways by which you can take action, the most obvious is to avoid plastic when possible and stick to reusable options. Bring your own utensils and plate to the next BBQ or potluck. It’s a great conversation starter, and you can take the opportunity to share what you know, perhaps swaying others to do the same. You can ask your local cafe to make more ecologically ethical choices about the cutlery they use. When plastic is unavoidable try to only use the types that can be recycled in your area. By far the best thing you can do is talk to your friends and family. Educate them on the importance of being mindful of the products they use. It really does make all the difference.

This article was written by Sean Porter.

You might also like: Arctic Lightning Strikes Have Tripled

![The Statistics of Biodiversity Loss [2020 WWF Report]](https://u4d2z7k9.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/lprwinkyTHB-544x306.jpg)