The ongoing pandemic has made it clear that when presented with similar circumstances of trouble or disaster, different people react in vastly different ways. The varied responses to COVID-19 across nations and communities resemble the typical responses to another big crisis that isn’t so easy to fully grasp, that of climate change. Studies on how these two issues are perceived sheds light on how to better communicate them in a way that garners more positive, sustained collective action.

—

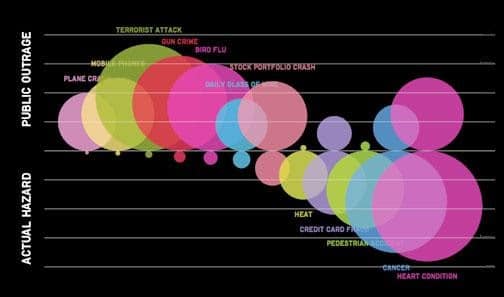

How one first perceives a crisis has a lot less to do with the facts of a situation than with their own psychology and socio-cultural background. We’re hardwired to assess risk based on various unconscious emotions and use past experiences, social cues, or feelings of control to fill in partial information. Hence our perceived sense of danger often doesn’t match how dangerous a thing really is. See the data for ‘public outrage’ versus ‘actual hazard’ below, for things like gun crime and credit card fraud. A typical example is how we drive our cars on busy highways every day but get anxious for an overseas flight even though plane crashes are far less likely statistically.

Source: Susanna Hertrich.

The Psychology Of Risk, And How To Leverage It

First off, things like climate change don’t immediately trigger our intuitive sense of threat, developed throughout millennia of evolution. Harvard psychologist Daniel Gilbert has written about what drives individual behavior and why climate change is often met with indifference.

A situation prompts response when it has four typical aspects:

- The intention of a tangible agent

- The extent it violates our sense of morality

- The immediacy of danger

- Whether any effects are instantaneous rather than gradual

Global warming is pretty benign by these standards, as is an invisible pathogen that hasn’t really bothered you or your immediate family. But see then how narratives can be framed so that people pay more attention.

To appeal to a perceived intention, we can use the subject-verb: it is not that the globe is simply warming – there are specific agents causing that warming, be they fossil fuel companies or governments uncommitted to net-zero policies.

To appeal to senses of morality, we can tell about the unfairness of climate change. Take the fact that the poor, in tropical, economically underdeveloped nations, will be most affected by increasingly extreme weather events (e.g. hurricanes and heatwaves) consequent of carbon emissions that they are largely not responsible for. Two-thirds of total global greenhouse gas emissions come from only a handful of developed or rapidly developing countries like the US, the EU, Russia and China.

And to appeal to immediacy, we can share stories of people already grieving losses due to warmer temperatures. The Midwestern farmer, whose crops cannot survive prolonged heatwaves and dry spells, causing him to give up the land he’d inherited from his father and grandfather and generations past, a tremendous loss of purpose and identity. Or the Pacific island nations of Kiribati and Tuvalu consistently, visibly going underwater as sea levels rise, submerging not just land but history, cultures and ancestral homes.

The Sociology Of Assessing Risk

Even with these appeals, though, risk perception is also strongly socially constructed, with some researchers arguing that outer influences are perhaps stronger than internal, psychological ones when it comes to what drives behavior. Interactions with colleagues, social norms, and the dominant media all shape what we believe we ought to think and do.

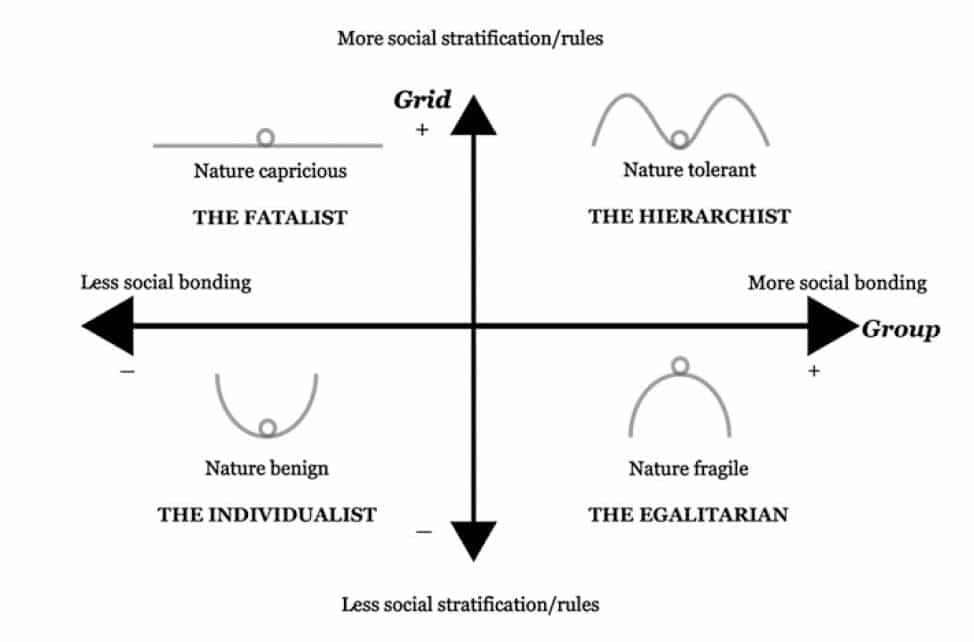

There is what’s known as ‘the cultural theory of risk’ which maps social groups into four broad categories based on whether they are community-oriented or individual-oriented, and whether they see rules and authority as necessary or not so much. These categorical worldviews then shape how people see the built and the natural world, and in turn how they perceive messages about climate and public health.

Source: McNeeley and Lazrus, 2014.

Societies that are more individualistic and that disregard regulation tend to see climate change as not such a big deal, with manageable consequences that are ultimately one’s personal responsibility. More community-oriented groups see climate change as more serious and requiring swift mitigation.

The cultural theory of risk has been debated and developed in recent decades but the main idea stands and generally follows what we see in today’s world.

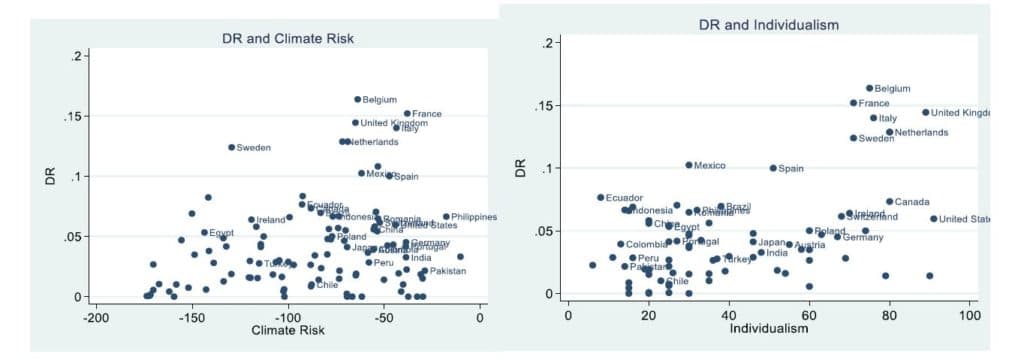

In a recent study, Ozkan et al. analyzed data from 110 countries and found that the more individualistic a country, the worse it was at handling climate emergencies and the COVID-19 pandemic, evaluated by each nation’s rate of mortality. In fact, the correlation between individualism and the COVID death rate was very similar to that between the COVID death rate and a nation’s climate risk – its vulnerability to damage from extreme weather events, based on physical geography but also readiness via policies and plans. This suggests that individualism may be a proxy for climate risk or vice versa.

COVID-19 morality/death rate (DR) versus Climate Risk and Individualism for different nations. Source: Ozkan et al, 2021.

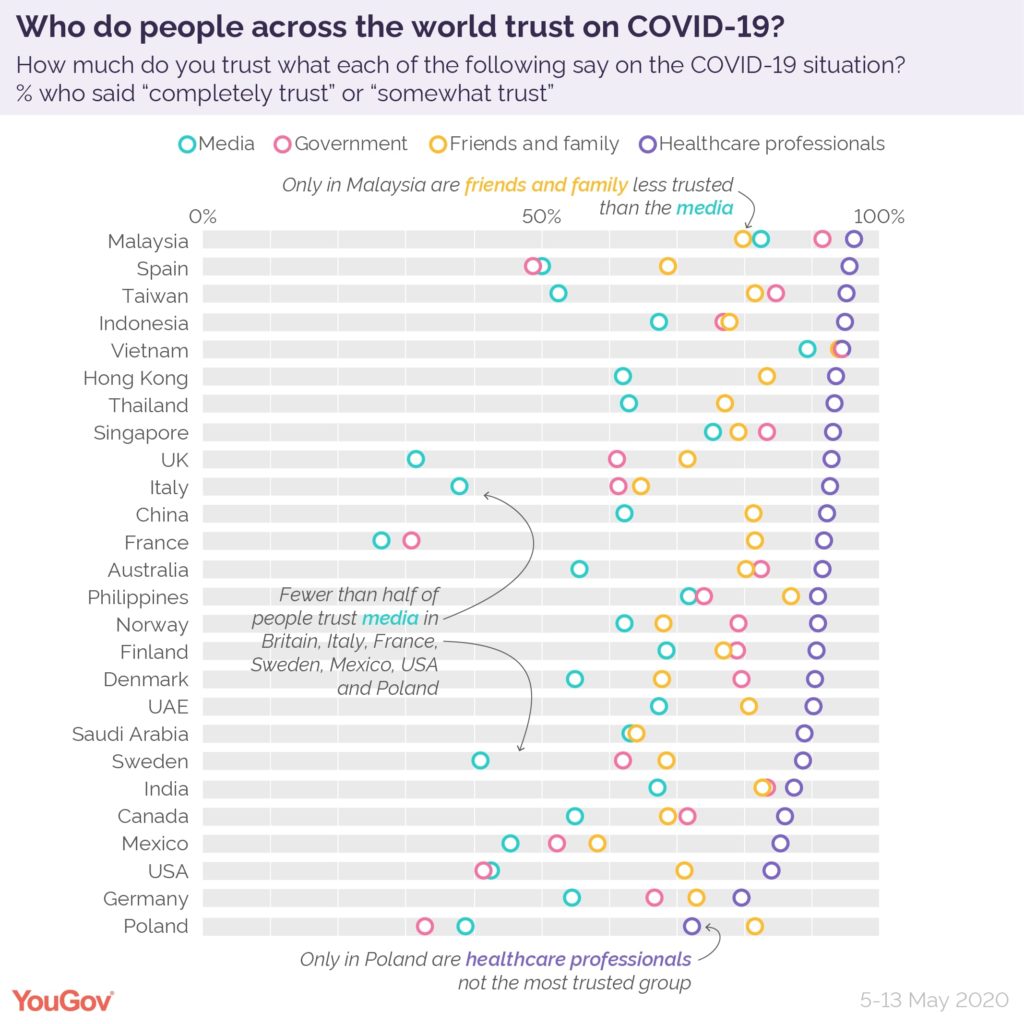

Perhaps the most influential societal factor in perceiving a crisis is one’s trust in those conveying the information, like public health officials or climate scientists, and this is rarely based solely on the speaker’s credentials. It’s based on who and what they represent, or appear to, and if people have ever felt misled by them. Once a level of trust is established, it can be very hard to change.

Trust in institutions like the media and government varies across societies, and again one can spot patterns along countries with similar socio-political worldviews. A YouGov poll from last year in regards to information about COVID-19 showed most people do trust healthcare professionals while news outlets and politicians consistently fare worse.

Again, recognizing all this can guide us towards better communication. We can appeal to a group’s specific values and recognize barriers that make certain efforts unproductive.

A governor’s press conference is less likely to resonate with a French or American audience, and in Southeast Asian countries like Vietnam and the Philippines the views of family and friends might carry a bit more weight.

To Keep From Tuning Out Catastrophe

So what about when a crisis is fully, rightfully perceived – when we’ve made it past our instincts and social lenses to recognize that a real problem is at hand?

In situations so vast and calamitous as a pandemic or global change, we often quickly realize that it is much more than any one of us can solve alone. The spark of wanting to do something can slip into overwhelming inability, and we freeze. We go into self-preservation mode, turning away from perceived helplessness and despair.

Anthropologists have studied how and why good, well-meaning people have been historically indifferent to famines, mass murder and genocides, and it seems that when faced with crises so immense a sort of psychic numbing takes place – people stop caring, and so stop trying to enact change.

Is there a way to change this, to change the reluctance to change? Again, we can improve the narrative. We can tell stories in a way that better inspires action.

Here are four strategies:

- Identify not only what is wrong but what the alternative could be. When the topic is habitat loss, paint the picture of abundant wildlife and vibrant ecosystems to highlight the kind of world we want to live in.

- Incite hope and gratitude, not just grief and anger and despair, to maintain social and environmental movements. The latter are powerful motivators but positive emotions lead to more sustained engagement.

- Explain the how and why of a situation as best as possible. The more we understand a situation, the more efficacy and agency we perceive, recognizing how even little actions do contribute to the big picture.

- Lay out concrete solutions that one can pursue now, drawing from a range of resources and talents that different people possess. An artist may not be able to donate significant finances to a rainforest conservation organization but they can spread awareness with their craft, and that is huge.

Anthropogenic climate change and the COVID-19 pandemic are not the first global crises to afflict the modern world, but they are among the first where we have access to an enormous amount of information and competing voices with which to judge what’s real and what’s not, or what matters more and what matters less.

As communicators (and, really, that is all of us), it is critical to know these influences well if we are to guide from seeing, to understanding, to doing something about it.

This article was written by Debbie Sanchez. Cover photo by Mathilda Khoo on Unsplash

You might also like: Adopting a Plant-Based Diet Would Reduce Agricultural Land Use by 3/4

![The Statistics of Biodiversity Loss [2020 WWF Report]](https://u4d2z7k9.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/lprwinkyTHB-544x306.jpg)