Plastic-eating bacteria are an exciting prospective solution to plastic pollution, but are they enough?

Earth.Org takes a closer look.

—

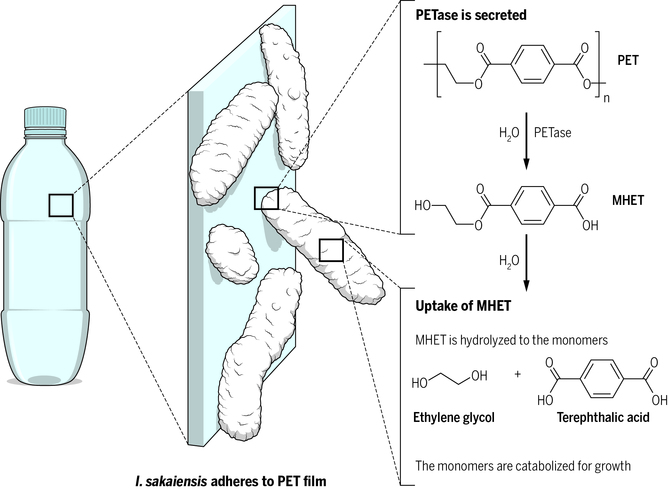

Headlines blew up in 2016 when a study from the Kyoto Institute of Technology discovered that the bacteria Ideonella sakaiensis can break down PET using the enzyme PET hydrolase and MHETase. Though this is an exciting discovery, there are currently many challenges that stand in the way of it being a marketable solution to plastic pollution or recycling.

Source: Yoshida et al. (2016).

At the moment, most plastic recycling is thermo-mechanic, which doesn’t fully degrade the plastics into its monomers (the “building blocks” of plastic). It tends to produce lower-quality plastics. Enzymatic degradation could degrade PET into its inert monomers. For the enzyme to be useful, it has to work fast, be marketable, safe, and deployed where plastic pollution is most abundant.

We are currently on track to have the same mass of plastic pollution in the oceans as fish by 2050. Theoretically, dumping lots of plastic-munching bacteria into the oceans seems like a great idea. However, unleashing genetically modified and untested species into new environments could have many negative consequences. Besides, scientists have found that plastic-eating organisms are already present in the ocean and account for the fact that aquatic plastic pollution is not present at the levels we expect.

The speed of these enzymes is also a key factor. If they can’t degrade hard plastic fast enough, they’re useless in the recycling process. PET is manufactured in varying levels of crystallisation; the more crystallised the plastic, the harder it is to break down. The study afore-mentioned used a small, low-crystalline PET sample, and it still took six weeks to be broken down. The enzyme has been improved since then: in 2018, UK scientists discovered the structure of PET hydrolase and modified it, accidentally causing it to work faster and on crystallised PET. In April 2020, the French company Carbios released a modified enzyme that could degrade 90% of PET bottles within 10 hours, though it still required a temperature of above 70°C. In October 2020, UK scientists combined the two enzymes involved in the plastic breakdown process and created a more efficient version that could work at room temperature.

These are significant improvements, but the risks involved in plastic degradation are still relatively high. Plastics contain toxins that may be released upon degradation. Next, the broken down plastic needs to be isolated from the other elements of the mix to be made reusable, which adds to the cost. Even if the degradation process was made cheaper and quicker, making plastics de-novo remains difficult to compete with. However, companies like Carbios are currently working on making this a viable marketable solution, and are collaborating with l’Oréal, Nestlé Waters, PepsiCo and Suntory Beverage and Food Europe.

Whilst enzymatic plastic recycling has huge potential, we are already producing 270 million tonnes of plastic waste yearly, and scalable solutions need to be found now. The solution will likely be a combination of many approaches, including reduced production, governmental incentives, and better recycling infrastructure.

This article was written by Cara Burke.

You might also like: Species Reintroduction: How Wolves Saved Beavers in Yellowstone

![The Statistics of Biodiversity Loss [2020 WWF Report]](https://u4d2z7k9.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/lprwinkyTHB-544x306.jpg)