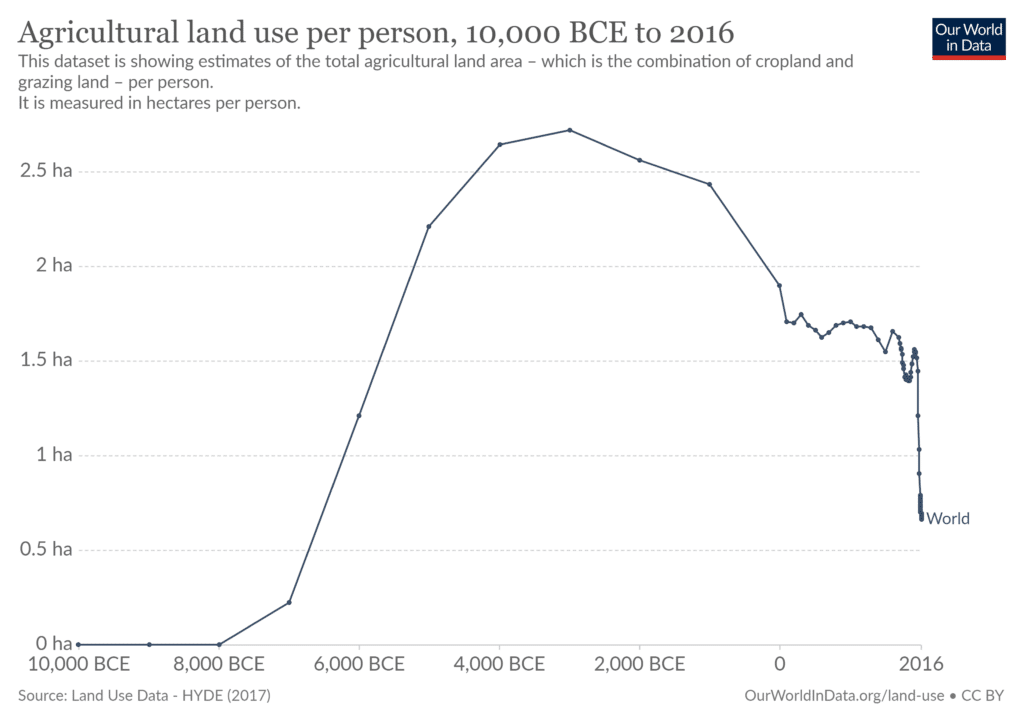

Agriculture changed the world around 10,000 years ago, allowing us to produce enough food to support the growth of cities and nations. Since then, agricultural land use has exploded, engulfing around 50% of all habitable land, of which 77% is dedicated to livestock and the rest to crops. Aquaponics has emerged as one of the most interesting alternatives for food production, and we review its viability in this article.

—

As you can see in the figure above, our agriculture area per person has dropped as productivity for a given unit of land increases along with population levels. The recent sharp drop in the ratio isn’t as rosy as it seems though, since it is the result of an overuse of fertilizers and mono-crop techniques that are degrading soil quality around the world. The approach simply isn’t sustainable in the long-term, especially since the human population is far from its peak. The earlier we implement scalable solutions, the more we mitigate damage to the environment and ease the transition.

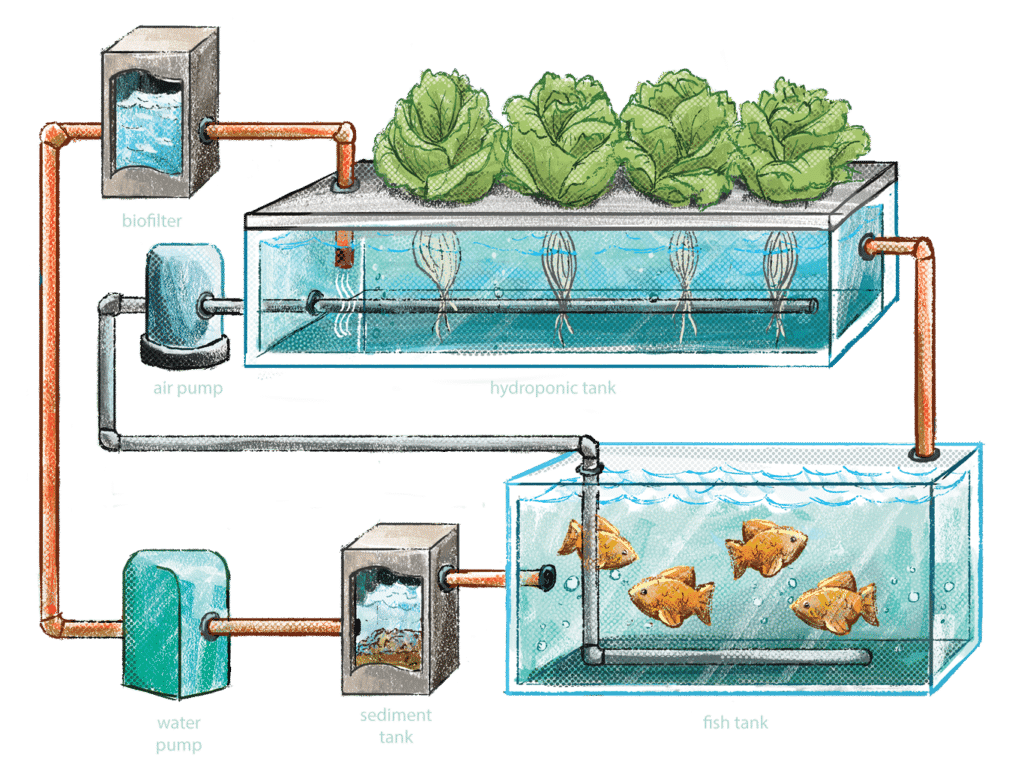

Of the viable solutions, aquaponics has gotten a lot of attention. The idea is to couple aquaculture, or the farming of aquatic animals, with hydroponics, a method for growing plants with water systems and no soil. The advantages are immediately apparent: by doing away with soil, we rid ourselves of the usual area to yield ratio, and open the possibility of vertical organization.

Source: Greenlife.co.ke

How do the plants still get the nutrients they need despite the lack of soil? This is where the aquaculture part comes in. The fish, duck or other species living in their own enclosure do the usual, swim, eat, defecate, repeat. The excrements are then cycled through the hydroponic system, bringing the necessary nutrients to the crops. Some use alternatives, such as chemical fertilizers and artificial nutrient solutions.

Source: https://ag.purdue.edu/envision/the-big-idea-hydroponics-aquaponics/

Beyond the spatial advantages, hydroponics (and therefore aquaponics) saves a lot of water compared to agriculture. As an example: 1 kg of tomato with intensive farming methods requires 400 liters of water, while hydroponics needs about 20 (95% reduction).

Seems great right? Unfortunately, it has some limitations. First, there isn’t a huge diversity of crops that can actually be grown this way. The main ones are tomatoes, strawberries, peppers, cucumbers, lettuces, marijuana, and scientific model plants. Notable families that don’t make the list are potato, carrots, and all other root vegetables, although more R&D in the area could unlock new possibilities.

Construction and maintenance costs are also important to consider. A backyard aquaponics system can go from USD $2,000 to USD $11,000 just for the initial set up, after which come the animals, the maintenance labour, and high water and electricity bills. A certain level of expertise is also required, as aquaponic systems are a bit more complicated than your average IKEA cupboard.

Briefly mentioned above is electricity usage. It is very high. Fish tanks need to be kept at an appropriate temperature 24 hours a day, which, depending on the location and energy source, can also have quite a carbon footprint. As we transition to cleaner energy globally, this will become less of an issue.

The limitations described above stand in the way of aquaponics being a solution to global food insecurity, at least for the moment. Organisations in Mexico and sub-Saharan Africa have taught aquaponics to those in need, reducing their reliance on imported food and unproductive land. Its potential is huge, but scalability will most likely need time, and governmental aid.

This article was written by Owen Mulhern.

You might also like: The Past, Present and Future of The Sahara Desert

![The Statistics of Biodiversity Loss [2020 WWF Report]](https://u4d2z7k9.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/lprwinkyTHB-544x306.jpg)