Desertification is an increasingly widespread problem as climate change modifies weather patterns, leaving people to deal with hyperarid conditions. The Sahara Desert is no exception, steadily growing across 11 countries and soon to cover more. Here, we take a look at the past, present and future of the Sahara, based on a 2018 study by Natalie Thomas and Sumant Nigam.

—

PAST

The Sahara Desert formed around 7 million years ago, as a great dust bowl sitting where the Tethys sea once soaked. This huge body of water separated the two supercontinents, Laurasia and Gondwana, resulting from the cleaving of Pangea by tectonic forces. Their pieces were shuffled, and the African plate slammed into the south-western Eurasian plate, creating the Alps and Himalayas, and enclosing part of the Tethys sea. Time flew by, and as the sea kept losing ground, it shrunk into the Mediterranean.

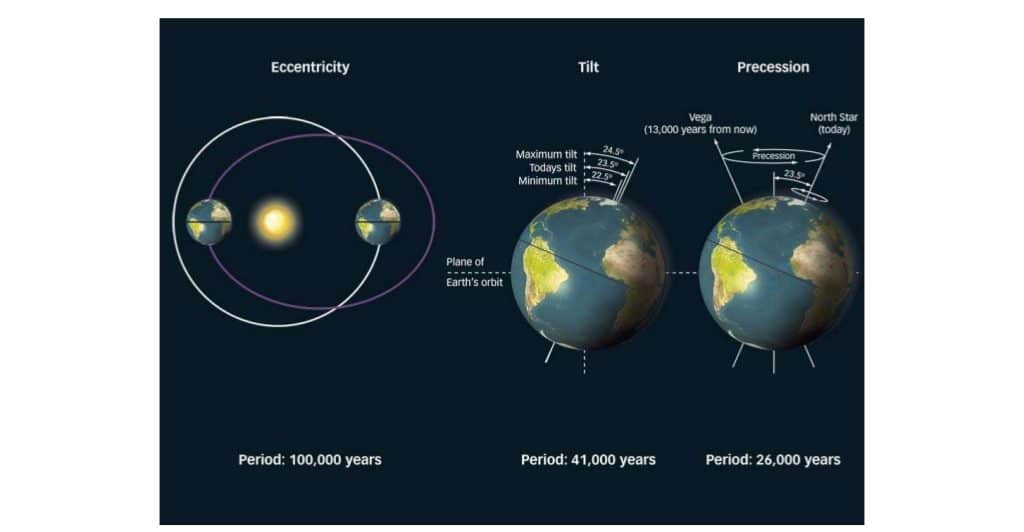

Until this point, the Sahara region wasn’t so dry, but the replacement of the Tethys Sea with land, reflecting less sunlight and evaporating less water, changed its weather patterns. Since then, the Earth’s Milankovitch cycles, namely the 100,000 year orbit eccentricity cycle, the 41,000 year cycle in the Earth axis obliquity and the 20,000 year cycle in the wobble of said axis (precession) – have impacted the African climate on long timescales.

The cycle with the most influence is also that on the shortest cycle, i.e. precession. It shifts the time point where the Earth has its closest pass to the Sun (perihelion), thus moving the equinoxes. 10,000 years ago, around half a precession cycle ago, this occurred in northern hemisphere summer, making solar radiation over North Africa 7% higher than it is today (Berger, 1988).

PRESENT

Deserts usually form in the sub-tropics due to airflow rising from the hotter equator and dropping back down around the tropics. However, scientists have observed that tropical latitudes are moving polewards at a speed of 30 miles per decade, and thus, the deserts within are expanding.

Indeed, analysis of rainfall data shows that the now-dry Sahara has been growing, covering 10% more land since records began around 1920.

Why is this happening? Natalie Thomas and Sumant Nigam, authors of the study, say that about two thirds of the change observed may be attributed to natural cycles, but the remaining, non-negligible third is due the human-driven shift in the tropics.

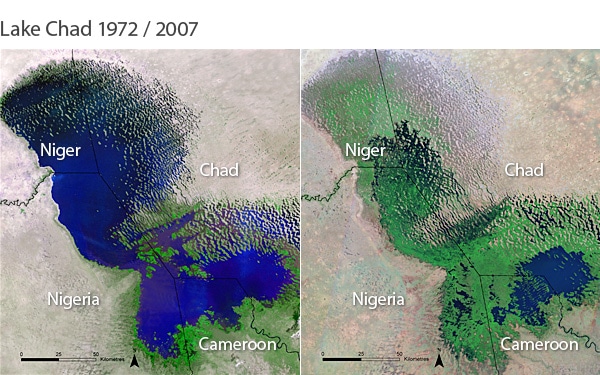

The result? Lake Chad, a landmark in the transitional region between the desert and the fertile savannas, the Sahel, is a good indicator of the slow but steady desertification that is occurring.

Of the 20 million beneficiaries of Lake Chad’s water, 80-90% live off agriculture, livestock and fisheries. The dwindling of the region’s lifeblood resource threatens it with food insecurity and conflict.

Libya, which used to be mostly non-desert in 1920, is now mostly desert, having experienced a 500 km advance of the Sahara during the dry season.

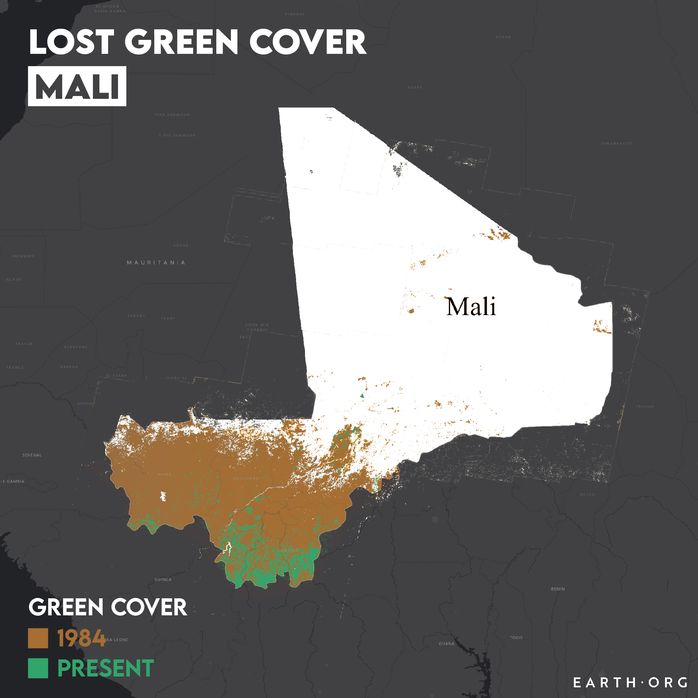

Mali is located in West Africa, straddling the Sahara so 65% of its area used to be desert or semi-desert. The country is plagued with conflict which is partly driven by climate change-worsened drought. The Sahara is growing at a rate of 48km per year in the area, exacerbating food insecurity and further feeding Mali’s instability.

FUTURE

Natalie Thomas, author of the study that quantified the Sahara’s century of growth, asks: “Morally, how do we deal with the fact that developing countries are paying the price?”. This question is at the heart of most climate issues – the poorer are set to bear the brunt of the impact.

Developing countries in the Sahel region are already plagued with extreme weather, floods, droughts, locusts and conflict. It is a near impossible task to deal with all of these issues at once, yet each exacerbates the others.

Only when problems begin to affect wealthier nations do these find impetus to act, and even then, still at a sluggish pace. For example, the state of Florida is being submerged with rising sea levels, yet part of the US government still doubts climate change is real. The Sahara situation is similar: desertification could actually spread across the Mediterranean Sea into Europe within the next century, which would certainly stir up its member states.

Strategies to reduce desertification exist, and include erosion control, vegetation upkeep and general soil health maintenance. Widespread efforts will have to be made on the part of the concerned nations, but as mentioned above, these have a lot to deal with. Hopefully help will be provided to prevent what could become a serious problem in the long term.

This article was written by Owen Mulhern.

REFERENCES

- Berger, A. Milankovitch theory and climate. Reviews of Geophysics 26, 624-657 (1988).

- Thomas, Natalie, and Sumant Nigam. “Twentieth-century climate change over Africa: Seasonal hydroclimate trends and sahara desert expansion.” Journal of Climate 31.9 (2018): 3349-3370.

This story is funded by readers like you

Our non-profit newsroom provides climate coverage free of charge and advertising. Your one-off or monthly donations play a crucial role in supporting our operations, expanding our reach, and maintaining our editorial independence.

About EO | Mission Statement | Impact & Reach | Write for us

![The Statistics of Biodiversity Loss [2020 WWF Report]](https://u4d2z7k9.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/lprwinkyTHB-544x306.jpg)