Coal has fuelled our technological progress for over 200 years, and the resulting carbon emissions are beginning to take a toll on our climate. While we are aware of the need to phase it out of our society, the need for cheap energy and economical engagements have made this a difficult process. Only now are we beginning to see a significant divestment in one of the dirtiest energy sources on earth.

Earth.Org takes a closer look.

—

The Origins of Coal

Coal is the result of plant species that have decomposed over millions of years into a substance known as peat. As the years pass, the peat is buried in layers of soil and moisture where temperature and pressure over millions of years condense the carbon into coal. The largest deposits are found where vast tropical wetlands of the Carboniferous area used to lay, over 300 million years ago.

Coal’s Golden Millennium

The history of coal stretches back to the Middle ages where it fuelled smithy furnaces. As an easy alternative to dwindling timber reserves, its use expanded rapidly, accelerated by Thomas Newcomen’s invention of the single-piston steam engine in 1712. The true explosion came with the Industrial Revolution around 1780, when it provided the energy necessary to fuel the technological leaps of the time.

Today, it generates close to 40% of the world’s electricity, its capacity having nearly doubled from 1,000 to over to 2,000 GW in the last two decades. The need for cheap energy to fuel economic growth played a big part in this dramatic growth, but we are finally seeing signs of relent.

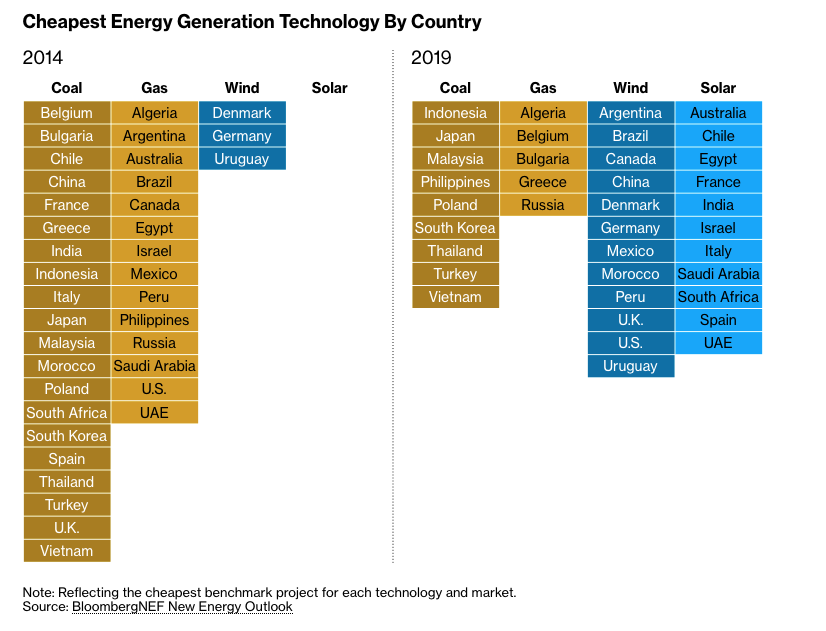

First, a 20 GW capacity increase in 2018 was the smallest in decades. Next, only 13 more countries intend to begin using coal power, down from 16 last year. Investment rates are plummeting, along with competing renewable energy costs, and we are witnessing the birth of a climate-aware pricing of carbon emissions.

Phasing Out Coal

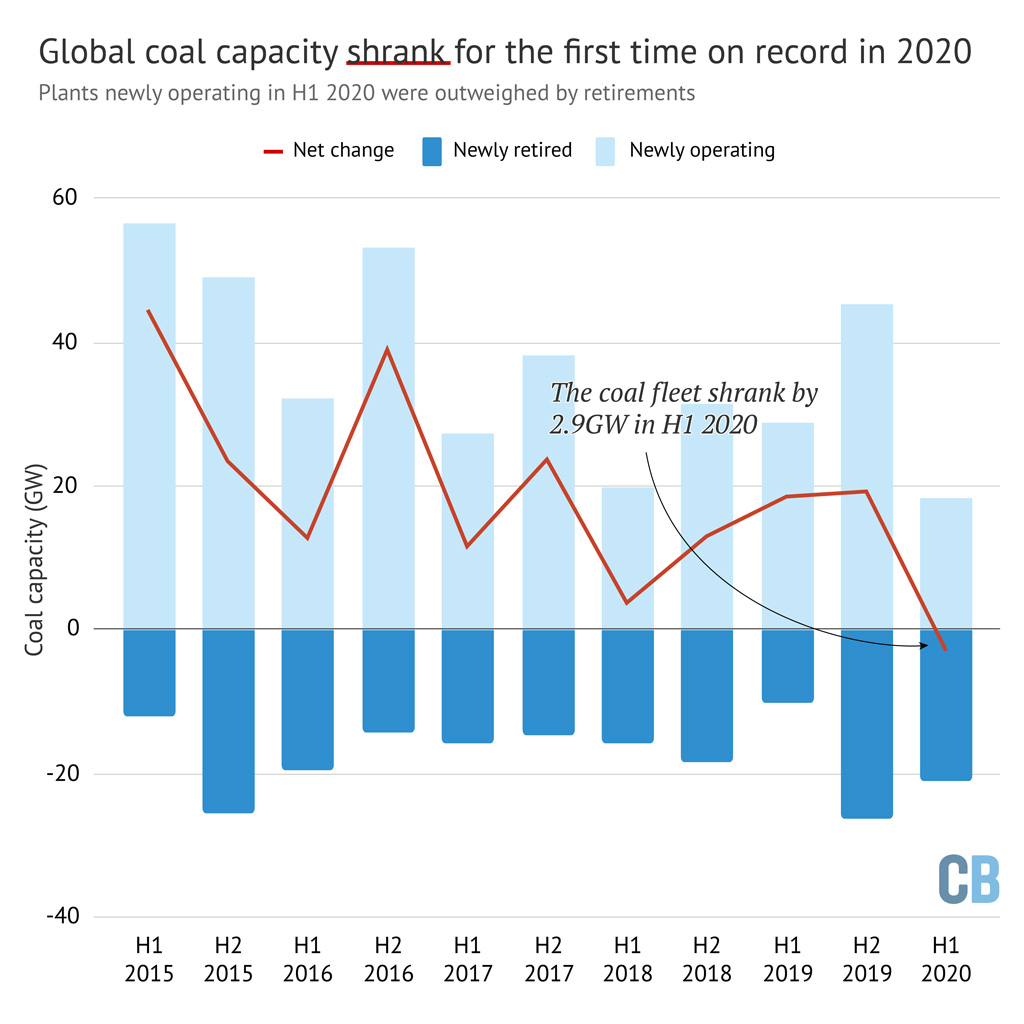

For us to stay under the 2C limit targeted by the Paris Agreement, we would need to completely phase out coal by 2040, requiring one coal unit’s retirement per day until then. Instead, we are only beginning to see a drop in coal investments, two steps behind the necessary divestment. In fact, global coal capacity is still rising as shown in this figure by the Carbon Brief.

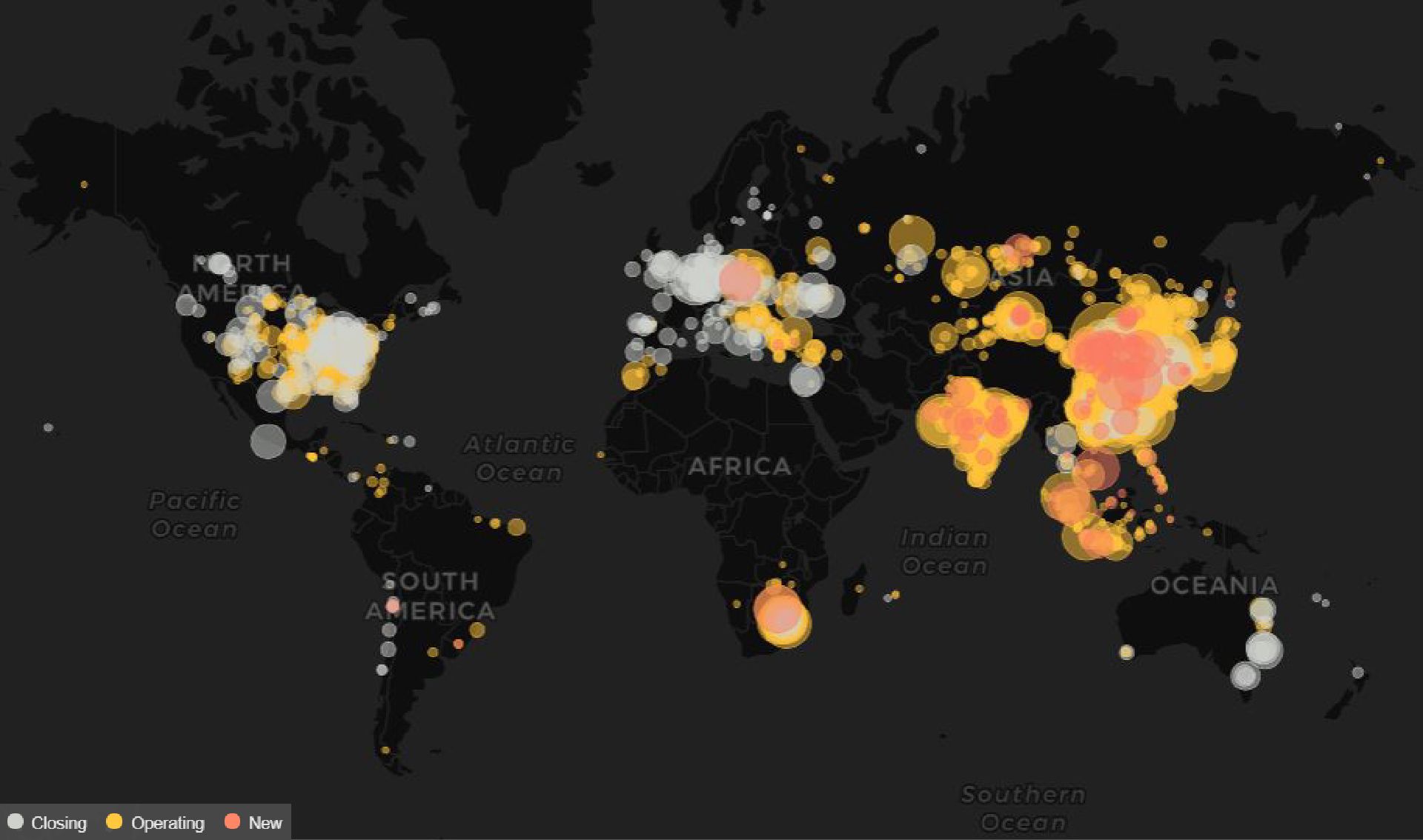

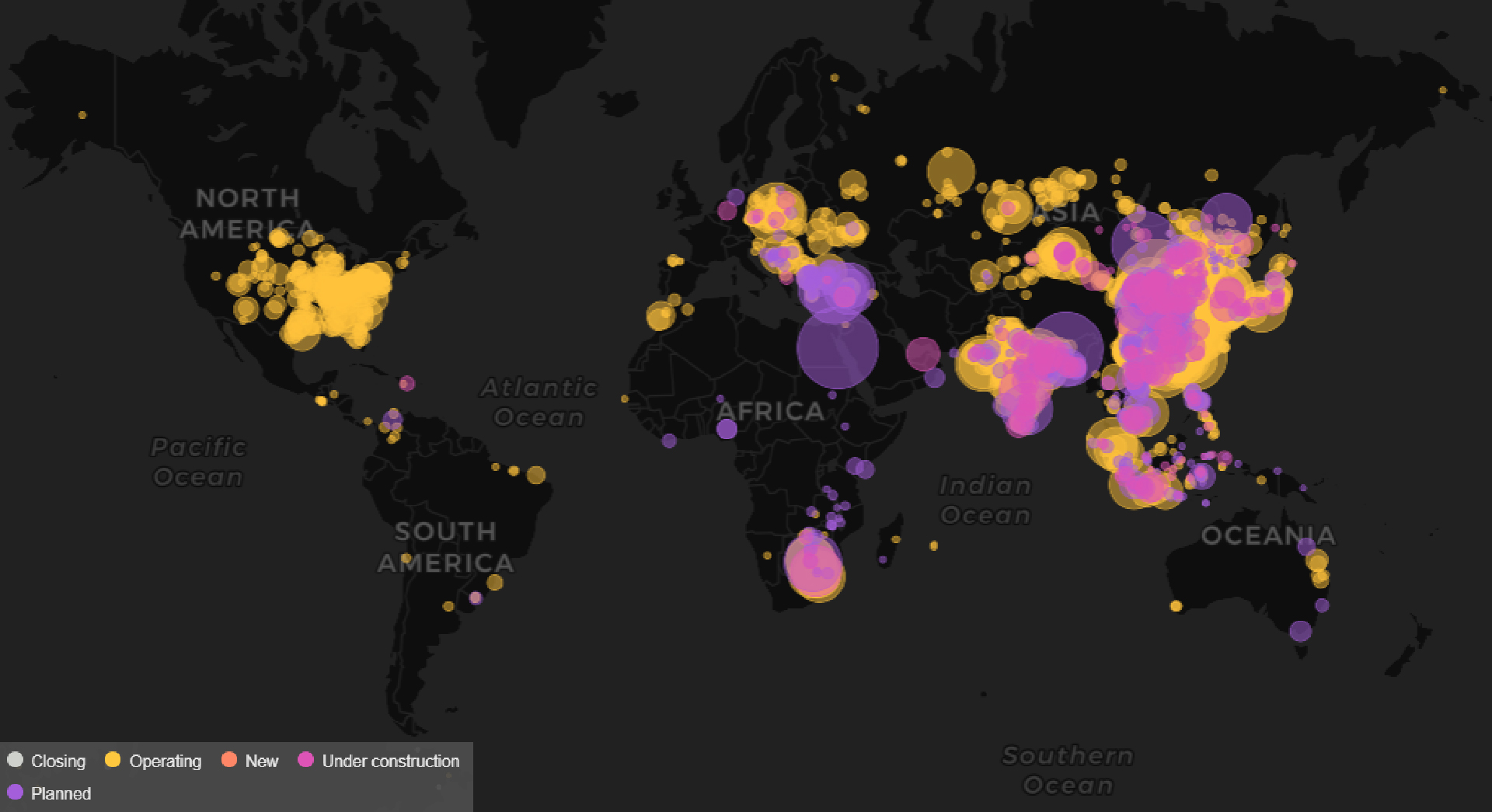

Thanks to the Carbon Brief’s analysis, we can visualize the current and future state of coal capacity. First, let’s take a look at today’s coal plant distribution, including those committed to retirement.

Global map of coal power plants in 2019, with bubble size proportional to the plant’s capacity. Source: The Carbon Brief.

Regional trends are immediately apparent in the map above. The US and Europe are beginning the phase out while India, China and Indonesia own the bulk of global operational facilities. Unfortunately, plans for the future are dishearteningly ambitious.

We often overlook Africa’s development when considering future emissions, but one could argue that renewables will outcompete coal before the continent comes up to speed with richer countries.

The Beginning of the End

Coal’s decline is too slow for us to meet the Paris Agreement goals, but it is accelerating nonetheless. Despite many more plants planned throughout China, India, Indonesia and Africa, increased competition from other sources and over-capacity is driving down investment in the sector.

Exemplary action like Germany’s recent parliamentary decision to speed up coal shutdown demonstrates our ability to put climate action before financial gain, a much needed trait if we are to remain under 2C global warming. Another encouraging statistic: for the first time since the Industrial Revolution, coal capacity shrank this year.

The net change in global coal power capacity (red line) between H1 2015 and H1 2020. (red line) between H1 2015 and H1 2020. Components of the net change are shown with additions (light blue columns) and retirements (dark blue), based on bi-annual updates of the GCPT. Source: Global Coal Plant Tracker, July 2020.

Despite the financial disadvantages, coal plants might remain open due to capacity market payments. Governments ensure electricity supply security by auctioning energy capacity provision four years ahead of time, meaning many coal plants will keep operating for a few more years before current market considerations come into play.

Prior engagements of the sort might explain why China is planning to build so many new plants, despite their construction offering no increase in coal-powered electricity generation. What the world really needs at this point is a correct valuation of carbon emissions, as suggested by the dogma of natural capital. Our planet’s resources are dwindling, both in quantity and quality, and it is time for our economic systems to reflect their true value.

This article was written by Liam Knevitt and Owen Mulhern.

You might also like: Antarctica Melt is Unavoidable, Regardless of Climate Action

Photo by Dexter Fernandes on Unsplash

![The Statistics of Biodiversity Loss [2020 WWF Report]](https://u4d2z7k9.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/lprwinkyTHB-544x306.jpg)