Overfishing is a serious threat to biodiversity and potential marine food supply. Depleting fisheries faster than they can replenish endangers key species in oceanic food chains, which can lead to the system’s collapse. Growing awareness of the risks has driven policy changes, but there is much room for improvement.

Earth.Org takes a closer look.

—

How Much Are We Overfishing? According to the State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture Report 2020, the number of unsustainably fished marine stocks has been increasing since 1974.

Source: The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations, The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2020, Sustainability in Action.

According to the OECD: “Fish landings are defined as the catches of marine fish landed in foreign or domestics ports. Marine capture fisheries landings are subject to changes in market demand and prices as well as the need to rebuild stocks to maximum sustainable yield levels in order to achieve long-term sustainable use of marine resources.”

78.7% of landings were considered sustainable in 2017. Looking at the 7 principal tuna species as an example, over 66.% of the global catch came from sustainable populations. Up from 56% in 2015, these numbers are still quite worrying – if 34% of tuna populations were to collapse, the effects would reverb throughout the entire world’s oceans.

Nonetheless, there has been a clear and encouraging decrease in average fishing pressure and a rise in average stock biomass, with many reaching or maintaining biologically sustainable levels.

What has been done so far?

The FAO launched a plan to regulate fishing in areas beyond national jurisdiction (ABNJ), which comprise 40% of the earth’s surface. They successfully reduced tuna overfishing and banned fishing from critically vulnerable areas, no small feat considering the countries with the largest catches are the US, China, and Japan.

One of the most effective policies to reduce overfishing are catch-share programs, which give out harvest allowances to individuals or companies. These shares can either be sold or used, and they incentivize smarter, timelier fishing rather than a “derby” kind of situation where boats race out every day to catch as much as possible.

The gigantic nets trawled around the world’s oceans everyday catch thousands of untargeted marine species, including sea turtles, birds and sharks. The FAO implemented a simple solution: placing the top end of the nets two meters lower. This reduced the mortality of marine mammal bycatch by 98% in the Indian Ocean.

Future Outlook

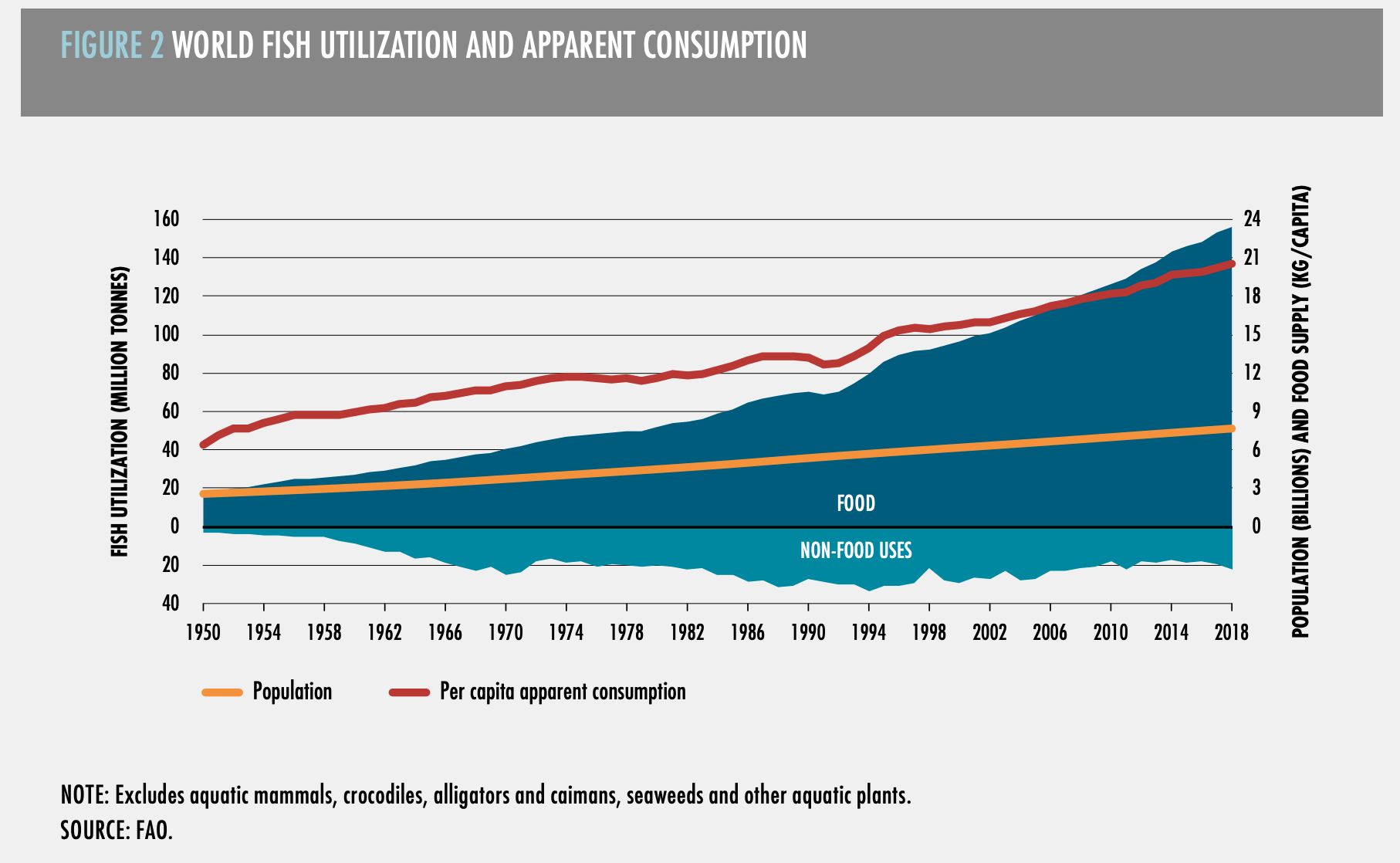

Although the FAO has launched various programs to combat overfishing, the overall fish consumption and production are expected to rise in 2030.

With the effect of rising incomes and urbanization, the demand for fish is projected to climb from 20.5kg per person in 2018, to 21.5kg in 2030. The total fish production (i.e. fish caught) is expected to increase from 179 million tonnes in 2018 to 204 million tonnes in 2030, while aquaculture production (fish farming) is expected to obtain an increase of 32%, although this number has been debated over.

Source: The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2020, Sustainability in Action.

Despite improvements over recent years, overfishing remains an issue. Our poor understanding of the ocean’s complex ecosystems makes it risky to push them to the brink; we hope that strong policies and global awareness will continue to create a more sustainable culture around fishing.

This article was written by Jennie Wong and Owen Mulhern.

References

-

World Wide Fund, Overfishing: An Overview, from: https://www.worldwildlife.org/threats/overfishing

-

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2020, Sustainability in action, Rome, from: https://doi.org/10.4060/ca9229en

-

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Overfishing of the world’s major tuna stocks going down, bycatch and pollution reduced and 18 new areas protecting vulnerable marine ecosystems established, from: http://www.fao.org/news/story/en/item/1258859/icode/

-

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Common Oceans – ABNJ, Global sustainable fisheries management and biodiversity conservation in Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction, from: http://www.fao.org/3/a-i7539e.pdf

![The Statistics of Biodiversity Loss [2020 WWF Report]](https://u4d2z7k9.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/lprwinkyTHB-544x306.jpg)