Air pollution is the third leading cause of death worldwide, and most large cities, have fine particulate matter (PM2.5) levels above WHO health guidelines. Here, we take a look air pollution mapping in Tokyo to better understand the current situation, and where things may be heading.

—

Because air pollution is directly linked to industrialization, this article will take a historical look at the advent of Japanese industry and its development during the last few centuries.

In 1843, Japan had long been a closed-off economy, only allowing foreigners to trade in the port of Nagasaki. This is why the arrival of four modern American warships in Tokyo Bay, with armament technology far more advanced than that of the Japanese, was a reality check. In the words of Shimazu Nariakira, “if we take initiative, we can dominate; if we do not, we will be dominated”, much like their Chinese neighbors had been by the English.

The country underwent a brief civil war between the reformist Meiji, who championed a western-style modernization of the country, and the conservatives who wanted to maintain the shogunate. The reformists came out victorious in 1869, ushering in a new era of industrialization, political reform, and pollution.

Things went fast, and within two decades, the country was hardly recognizable. Samurai now worked in local shops, western political and economic institutions had taken over, factories were everywhere, and the environment began to suffer.

Tokyo’s population was already above a million, and its urbanization and industrialization resulted in many environmental issues. Along with Osaka and a few other hotspots, it suffered from cholera, urban filth, black smoke, and offensive odors from animal processing plants. Ironically, heavy smoke emissions related to industry were often seen as a symbol of prosperity, and therefore rarely garnered complaints.

Still, there were a few air pollution cases around the time, like that of the Asano Cement Company. It moved to Tokyo in 1883 and its dust emissions began visibly covering the local neighborhood. Angry citizens demanded the removal of the plant, but the government did not intervene, leaving the citizens to endure until Asano introduced an electric dust collector in 1917 (32 years later).

This example is illustrative of the Japanese priorities concerning the “growth or green” problem, which each country faces throughout its development. In other words, how fast the government acts to mitigate the inevitable environmental damage that comes with industrialization.

Like many other cases (including but not limited to New York City, Melbourne, London and Johannesburg), early public protest in Japan resulted in weak legal measures, often short-scoped and poorly enforced. Tokyo and Osaka were the first to see a forced relocation of factories to designated industrial areas, with the term “kogai” (environmental pollution) appearing in written law around the same time (1882). The industrial areas were rapidly surrounded by houses again due to continuous urban expansion – signs of a growing awareness, yet of a lack of concern.

Not much happened on the air pollution control front until 1913, when the first Japanese smoke abatement committee appeared in Osaka. However, it’s attempts to impose regulation lost out to business interests for another 20 years, meaning industrialization went completely unchecked for 50 years.

Tokyo began its first air pollution monitoring program in 1927, which is a key step forward since data provides robust arguments for action. The city’s police force was also recording sharp increases in the amount of complaints at the time, yet regulatory apathy continued.

It took no less than the Second World War to shake things up, partly thanks to the rewritten constitution’s Local Autonomy Law in 1947. Local-level authorities were finally allowed to take matters into their own hands, and naturally they would be more responsive to their citizen’s pleas.

Communities began to combine the forces of government, university and industry to implement the first truly effective pollution control programs in the years between 1945 and 1969. Unsurprisingly, a strong wave of anti-insutrialism had formed by this time, and militants were able to exert more influence on a local scale. As a result, more regulation came through, like the decades-late (compared to other countries) Smoke and Soot regulation Law of 1962 – effective for controlling black smoke and heavy deposited matter, but leaving others like sulfur dioxide (SO2) out of its scope.

The balance was finally shifting, punctuated by the successful cancelling of a planned petrochemical industrial complex in 1964. Companies were now expected to be using the most effective pollution-reducing technology available, incentivizing other companies to research and develop better tech.

National air quality standards were finally set in 1967 with the Basic Law for Environmental Pollution Control Measures, and two years later, these were integrated into the energy supply program. Regulations were sequentially tightened and improved over the next decade, with the essential vehicle emission standards coming through in 1972.

The ensuing 70s and later 90s saw major breakthroughs in desulfurization technologies and low-sulfur oil, helping the country to satisfy SO2 standards by 2012.

The 70s were also the first decade in which the damage from photochemically produced air pollutants, that is new molecules formed by atmospheric reactions after an initial pollutant is released, was reported. It became clear that the scope of law had to expand, and regulations for all sulfur and nitrous oxide emitting sources were enacted. It was difficult to keep nitrous oxides in check since they are produced mainly by combustion and not directly from fuel content, and automobiles were multiplying. Still, many small changes like more fuel efficient vehicles, better urban planning and traffic control, along with other technological measures helped reduce emissions to an acceptable level.

The worst and most widespread form of pollution is that of fine particulate matter, oor PM2.5. It gets deep into our lungs and has deleterious health effects similar to those of cigarettes, including increased respiratory and heart disease occurrence.

Using Berkeley Earth’s PM2.5 to cigarette equivalence, we mapped what pollution looked like over Tokyo in 2016 (latest PM2.5 dataset) to illustrate the situation.

Air pollution mapping in Tokyo. PM2.5 data from NASA-SEDAC (2016).

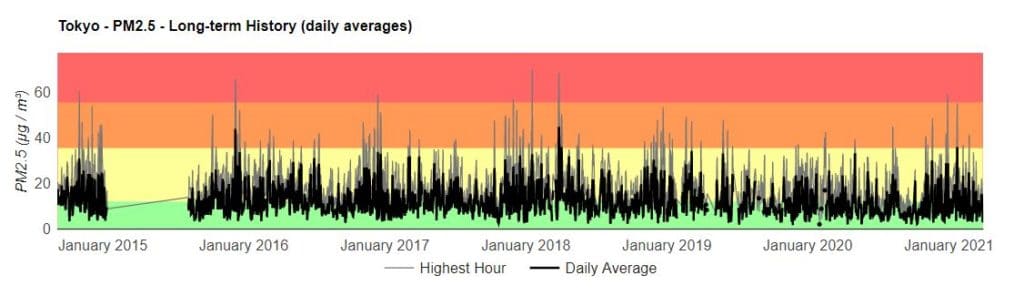

There has been progress since, and though the levels fluctuate a lot, Tokyo’s average PM2.5 levels are just above the WHO’s guideline (10md/m3) at a solid 12mg/m3.

Source: Berkeley Earth.

So where do things go from here? The biggest sources of air pollution in Tokyo are still vehicle emissions and factory fumes, with improvable levels of nitrous oxides. The authorities have established a plan to reduce PM2.5 under 10mg/m3 by 2030, mainly through subsidizing electric vehicles and continuing to tighten regulations on diesel vehicles and industry.

It is an incremental process that will take time, yet is entirely solvable and Tokyo is doing it correctly.

This article was written by Owen Mulhern.

You might also like: Outsourcing Deforestation: The Local vs. the International Footprint

![The Statistics of Biodiversity Loss [2020 WWF Report]](https://u4d2z7k9.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/lprwinkyTHB-544x306.jpg)