Air pollution is the third leading cause of death worldwide, and most large cities, have fine particulate matter (PM2.5) levels above WHO health guidelines. Here, we take a look air pollution mapping in Manhattan, NYC to better understand the current situation, and where things may be heading.

—

After its colonization in the 1600s, New York City rapidly grew into an important trading port due to its strategic positioning. Many historic events took place in the area throughout the 1700s, until it was made the nation’s capital in the latter part of the century.

The path was cleared for the city to prosper and expand, which indeed it did, growing from 60,000 to 3.43 million over the course of the 19th century.

During the same period, the Industrial Revolution changed the world, bringing about better means of transportation, production and engineering, but also launching the exponential increase in fossil fuel emissions that we have not yet seen the end of.

For the first hundred years of the United States’ existence, air pollution issues were settled by legal challenge between the concerned parties, with no specific legislation addressing the problem. It was around 1881 that the first legislation was enacted to specifically declare smoke emissions to be a public nuisance, after which municipal legislations began to multiply.

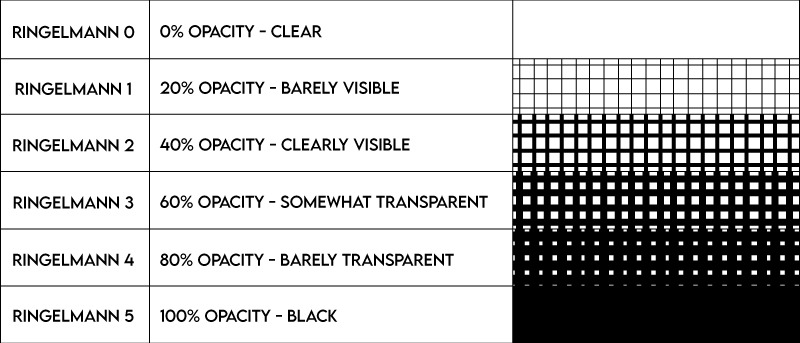

Most of the smoke abatement ordinances of the time generally prohibited smoke vaguely defined as “dense”, “black” or “grey”, to a certain number of minutes per hour. The poor definition based on color led to a later definition of smoke density by Ringelmann Chart number or percent opacity.

Around the turn of the century, records show that it became unnecessary to state that air pollution was a public nuisance, as it was self-evident from the smell, soot, and irritated eyes and throats. County-level laws then came about in the 1920s, and the first comprehensive state legislation appeared in 1952, Oregon.

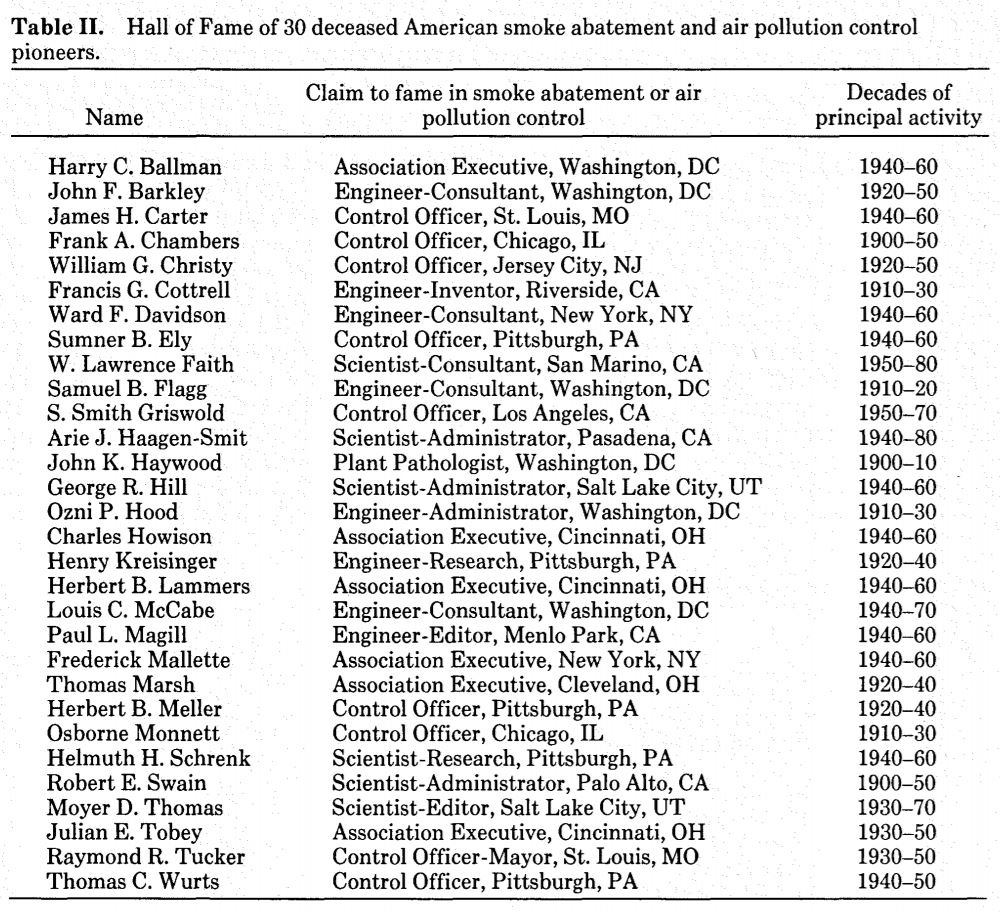

Many of the laws included in the table above failed to make a difference because the appropriate oversight, personnel, and/or fiscal means to enforce them were not provided. In fact, most early air pollution measures were ineffective, regardless of the country, possibly due to the fact that it was written into law as a nuisance rather than a threat. Yet the nefarious effects of air pollution on health had been described since the 13th century, when air quality first dropped to abysmal levels in London.

Arthur C. Stern explains that, were it not for a few great men, little would have been accomplished, and he shares his personal hall of fame, included here for your perusal.

Real attention to air pollution in New York came about with the 1928 installation of Owens-type air paper air filters that captured fine particles.

Set up in a number of key locations around the city, these provided much needed rudimentary data and gave way to a wave of studies. The main pollutant identified before World War II was sulphur dioxide (SO2) combined with soot from heavy coal combustion for heat and power production. This was addressed through the use of cleaner fuels (natural gas, better forms of coal, oil), higher smoke stacks and industrial gas cleaning in certain areas. However, the rise of the automobile replaced the SO2 with nitrogen dioxides and volatile organic compounds which can react in the air to create photochemical air pollution, the main component of smog.

These became notorious in the late 40s and early 50s as a common occurrence in Los Angeles, and a rarer albeit deadly one in New York City.

The first nation-wide piece of air pollution legislation, the Clean Air Act, came into play in 1963, meaning states could receive federal funds for their academic institutions, research programs and staff relating to air pollution.

This Act set the foundation for the next major advances in air pollution regulation including the 1970 National Ambient Air Quality Standard (NAAQS), setting the first health-based limitations on six air pollutants, including:

- Ozone (O3)

- Particulate matter (PM10) and fine particulate matter (PM2.5)

- Lead (Pb)

- Carbon monoxide (CO)

- Sulfur oxides (SOx)

- Nitrogen oxides (NOx)

A side note on lead:

Lead was introduced as a way to boost fuel efficiency by permitting higher compression ratios, and was sold in the U.S. as a “tiger in the tank” of your car. After being criticized for its potential environmental damage, its noxious effect on human health was also demonstrated, and lead was slowly phased out of gas in the developed world.

The Environmental Protection Agency took oversight of air pollution control and ushered in a new era of difficult, yet steady improvement in environmental policy. Some of the most notable changes were the use of catalytic converters to reduce carbon monoxide exhaust from cars and the change from ozone depleting chlorofluorocarbons to hydrofluorocarbons.

More evidence emerged in the following decades proving the danger of even low levels of pollutants, from ozone to fine particulate matter, prompting the EPA to tighten its regulations on all of these. There are now 189 controlled threats on the list, all much better understood than before.

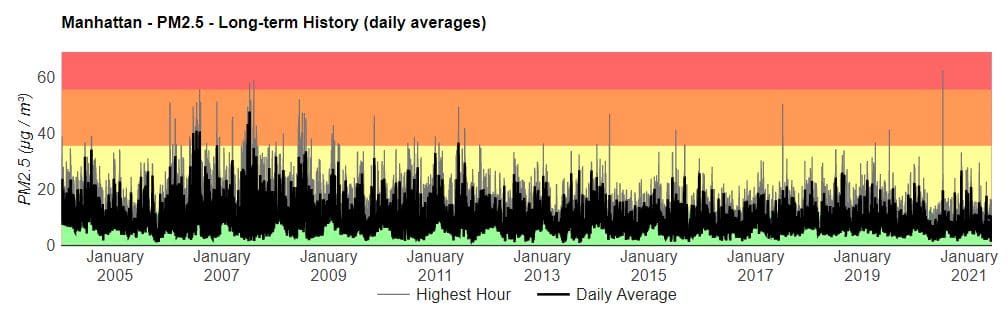

Source: Berkeley Earth.

Above, we see the long term PM2.5 levels recorded in New York City, courtesy of Berkeley Earth. The color ranges indicate the level of health risk associated with the PM2.5 according to the WHO’s guidelines, with 10 micrograms per meter cube being the recommended max.

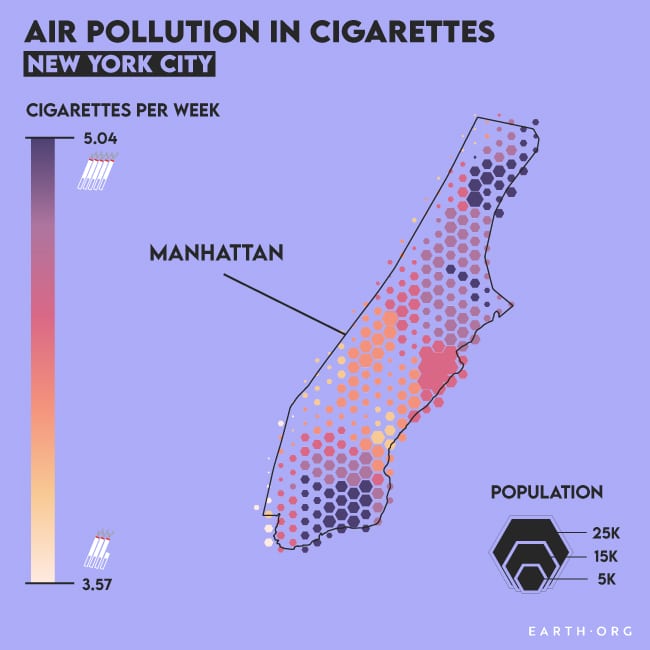

Using Berkeley Earth’s PM2.5 to cigarette equivalent in terms of health effects, we mapped air pollution over the city to give a more recent perspective on the situation.

Air pollution mapping in Manhattan, NYC. PM2.5 data from NASA-SEDAC (2016).

New York’s air pollution remains above the WHO’s recommended limits, and the health effects amount to smoking 3 to 5 cigarettes per week for its citizens. Far from negligible, it is also far from infrequent – over 90% of all humans are exposed to air pollution levels over the guideline limit.

This data pre-dates the COVID-19 pandemic however, so current pollution levels are far lower, although they are expected to bounce back shortly after activity resumes since authorities are more concerned with getting the economy going again than saving what environmental progress was made.

Not that they are wrong to do so; the pandemic hit New Yorkers hard, but it is a shame to see such environmental healing go to waste when we could use it to rethink how we do things. Of course, that would take more than a year and a half to implement. Things are already moving in the right direction, and the adoption of electric vehicles combined with cleaner energy is making a difference.

This article was written by Owen Mulhern.

You might also like: The History of Air Pollution in Johannesburg

![The Statistics of Biodiversity Loss [2020 WWF Report]](https://u4d2z7k9.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/lprwinkyTHB-544x306.jpg)