The Amazon is gradually getting drier, and in 2020, fires hit a 12-year high. Its regenerative abilities are being pushed to the limit, and if stronger restrictions and conservation legislation aren’t passed, it will eventually falter. Here, we review a set of images and maps produced by NASA, whose satellite instruments allow us to monitor the situation better than ever before.

—

Since the beginning of Jair Bolsonaro’s presidency in 2019, the Amazon has been burning at its highest rates since the early 2000s. NASA has been tracking the rainforest’s blazes thanks to satellite instruments for years, but it remains difficult to make out their causes: is it a seasonal agricultural fire burning in pastures, a brush fire, or a deforestation effort?

Dry years naturally have more fires than wet ones, and human activity can usually be derived from the location and frequency of fires. For instance, fires most often occur naturally in shrublands, savannahs, and the nearby Pantanal wetlands, than in Amazonia. But if there is an abnormal concentration of fires in an area near human settlements or highways, that is a smoking gun. High resolution imagery can also be applied to confirm suspicions more easily, but this can’t be deployed over the entirety of the burn zones for cost and time-consumption considerations.

The importance of this type of monitoring is to better guide the everlasting debates held within the countries concerned (mainly Brazil, but also Paraguay, Bolivia, Uruguay and Argentina). You often find completely contradictory claims on both sides of the issue; one says nothing of note is happening, while the other claims the forest is on the verge of dying. The truth is somewhere in between, and solid proof is the only thing that can settle it.

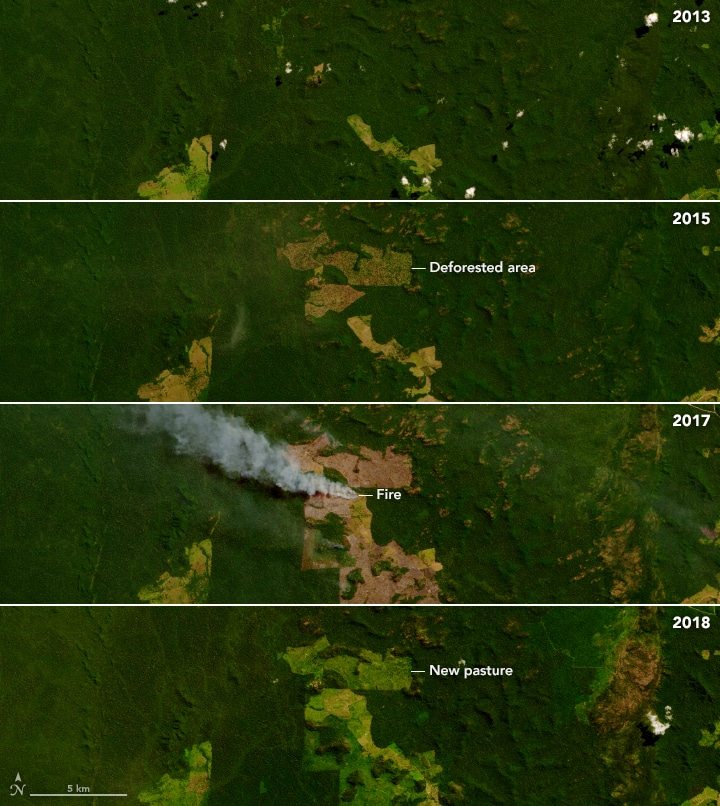

As we can see in the series above, deforestation fires a multi-step process that often begins years before ranches are fully set up. It starts with razing patches of forest with bulldozers or tractors, after which piled up wood is set ablaze during the dry season.

This year, NASA provides us with advanced imagery of the fires that occurred throughout the Amazon in 2020. Despite COVID-19, fire activity of all types rose significantly, including the two most environmentally destructive: deforestation and understory fires. Understory fires are entirely due to climatological mechanisms, burn slowly under the forest canopy and destroy more of the trees in their path than other kinds.

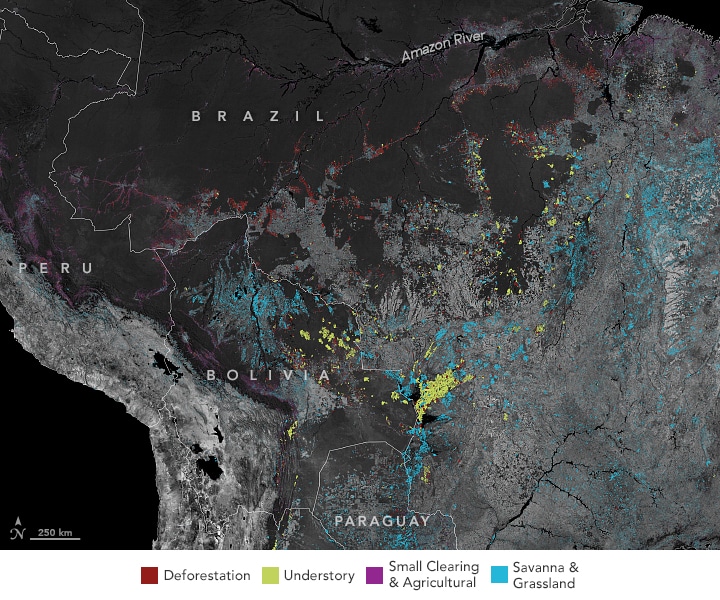

Douglas Morton, chief of the Biospheric Sciences Laboratory at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, headed the development of a tool that can sort fires into four groups: deforestation, understory, savannah-grassland and small clearing/agricultural.

In the map above, dark gray is forest cover, while light grey is the lack thereof, either because of deforestation or the natural layout of the land.

Small clearing fires are usually controlled and do not cause too much damage, but they can sometimes escape and cause underbrush fires (savannah-grassland types can also do this). Savannah fires cover a lot of ground, but regrowth is quick and damage does not persist, unlike the deforestation or underbrush types whose damage can last decades.

Atlantic ocean temperatures shifted rain away from South America in 2020, causing warmth and drought which fuelled many more fires than usual. Of the 600,000 detected, 25 were on par with the largest 2020 Californian fires, which were far larger than those of the past century.

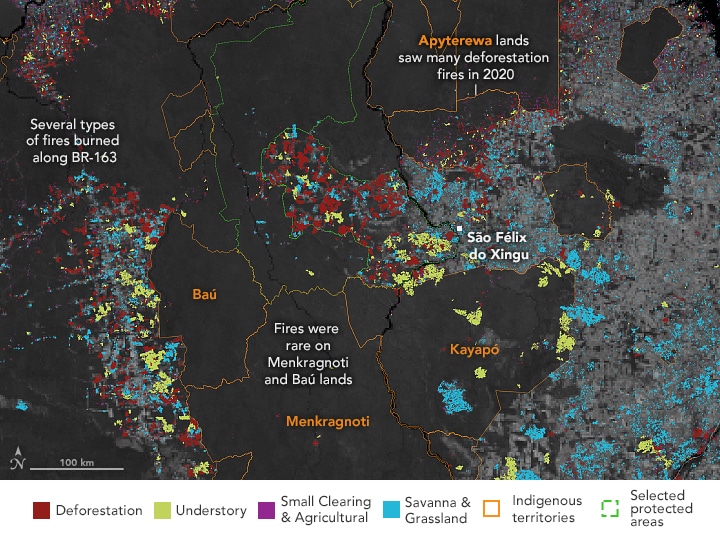

Large swaths of Amazonian land are official indigenous protected areas, but if the tribes within do not combat outsider development, these borders can be infringed upon

In the map below, notice how the Bau and Menkragnoti areas, whose people actively patrol their lands, remain untouched. Apyterewa, near São Felix de Xingu, a cattle town with over 2 million animals, is exposed to “grilheiros”, or land grabbers.

NASA is developing an Amazon dashboard to make their data as accessible and useful as possible for local decision makers who are trying to combat the fires. The work of various NGOs has also been effective in protecting lands, though they lack the manpower to stop all illegal activity.

NASA Earth Observatory maps by Lauren Dauphin, using data from the GFED Amazon Dashboard team. VIIRS fire data from NASA EOSDIS LANCE, GIBS/Worldview, and the Suomi National Polar-orbiting Partnership. Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey. Indigenous Territories and Natural Protected Areas data from the Amazon Geo-Referenced Socio-Environmental Information Network (RAISG).

Story by Owen Mulhern.

You might also like: Mapping the Mauritius Oil Spill

![The Statistics of Biodiversity Loss [2020 WWF Report]](https://u4d2z7k9.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/lprwinkyTHB-544x306.jpg)