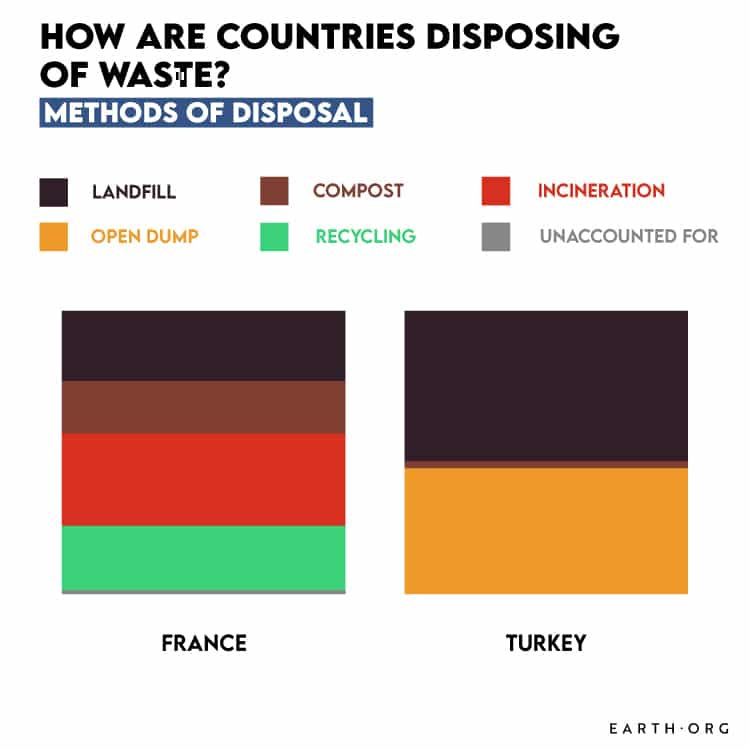

Waste generation has skyrocketed inthe past quarter century, and since China’s waste import ban, much of it has been impropoerly disposed of. Here we put the spotlight on management in France, one of the major exporters, and Turkey, currently the largest importer of EU waste.

—

From 2001 to 2018, waste shipments from EU countries increased drastically, from 6.3 to 20.9 million tonnes. Part of the load stays within the EU, but much of it is also exported to non-OECD countries, such as China, Malaysia and Vietnam.

A paradigm shift in the waste management world occurred in January 2018, when China notoriously executed the “National Sword” policy. Until then, it had been the main recipient of the world’s unwanted plastic, but sorting and environmental problems led to the government’s refusal to continue playing this role. Big waste exporters such as the US, Australia and the EU’s wealthier members were left with more than they could manage, and began sending it to lower-income southeast asian countries until these too had to curb imports.

Turkey has stepped up as one the largest recipient of EU waste since, taking in 11.4 million tons of their waste in 2019 – a threefold increase compared to 2004. This is creating visible environmental pollution, and the population is not happy about it, but various actors are happy to keep receiving the trash out of economic interest.

A 2020 OECD report ranked Turkey last among member-states in terms of waste recovery, meaning that little of its own recyclable materials make it to the designated facilities. Further, of the recovered material, there is no transparency as to how much of it is recycled, incinerated or dumped. Turkey still needs plastic to make it to its recycling plants in order to meet quotas and provide for its plastic manufacturers, which explains why it is importing so much. This benefits countries like France, one of the EU’s largest exporters of notified waste, along with Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands and Italy. Its shipments of hazardous waste more than doubled from 2016 to 2017, and have continued to rise since.

By Claudia Cheuk.

Another issue is illegal waste shipping, which consists in the smuggling of dangerous materials and compounds which a country has no right to export. France, despite a strict position against illegal waste shipping, lets some slip through its nets (as exposed when Malaysia sent back 42 containers of illegal materials to France).

Along with the poor internal waste management in

In Turkey this type of activity is tied with organized crime. They enable private entities in countries with stricter rules to cheaply send their waste over, then dispose of it at low cost and high damage to the environment.

Interpol reports and an increasing number of criminal complaints are putting pressure on the Turkish government to fight back. Environmental Minister Murat Kurum announced that legislators are planning to “prevent the import of high amounts of waste”, with an aim to improve domestic waste management.

The EU has committed to a green future and creating a circular economy, under which jettisoning the unwanted, dangerous materials it produces onto foreign, poorly regulated land is unacceptable. In a bid to take responsibility, the bloc imposed new rules in December 2020 tightening the regulations on exportable waste. While well-intentioned, France cannot stop all illegal activity, and it is incumbent upon Turkey to improve its waste management practices.

This article was written by Owen Mulhern.

You might also like: The Effect Of Sea Ice Decline On Polar Bear Habitats

![The Statistics of Biodiversity Loss [2020 WWF Report]](https://u4d2z7k9.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/lprwinkyTHB-544x306.jpg)