Nineteen of the twenty hottest years on record have occurred since 2001, not including 2020 which is on track to top the list. Now, research has found that climate change could make parts Mexico too hot to live in by 2070.

Earth.Org takes a closer look.

—

This case study is based on the paper “Future of the human niche”, published in PNAS by Xu, Chi et al. (2020).

As a species, we have historically avoided living outside of mean annual temperatures (MATs) between ∼8°C to 20°C. MATs above 29°C, found only in parts of the Sahara and Saudi Arabia, are generally considered too hot to live in. Of course, there are always exceptions. The city of Mecca in Saudi Arabia receives around 2 million Muslim pilgrims each year, densely packed under temperatures that can reach 50°C. The important distinction is the whether you must bear such heat for a single month or six in a row. One can be endured and avoided, six and your society can’t function.

It is difficult to define what heat threshold is truly impossible to live in because this depends on several factors. The first is humidity, as high levels can inhibit our ability to cool off via sweat. If the air temperature is 29°C, it will feel like 26°C with no humidity (Sahara), or 34°C with 70% humidity (southern Mexico). Physical fitness is also important – most heat stress victims are infants or elderly. Finally, we can spend our time indoors with extensive air conditioning networks, but this isn’t always available outside big agglomerations.

Southern Mexico is known for its beaches and sunny weather, but according to Xu et al (2020), the majority of its coastline will warm up to reach MATs above 29°C by 2070. This means Sahara-like temperatures with far higher humidity, making it unbearably hot to live for long periods of the year.

The high MAT area on the Caribbean coast engulfs the regions of Tabasco and Campeche. An exceptional 45% of Tabasco’s population lives in rural areas, and the region’s economy is heavily dependent on agriculture; in Campeche, agriculture and fishing are the most prominent activities, along with mining. There are few crops that can tolerate such heat, and fishermen who depend on their catch will be unable to go out at sea under searing temperatures.

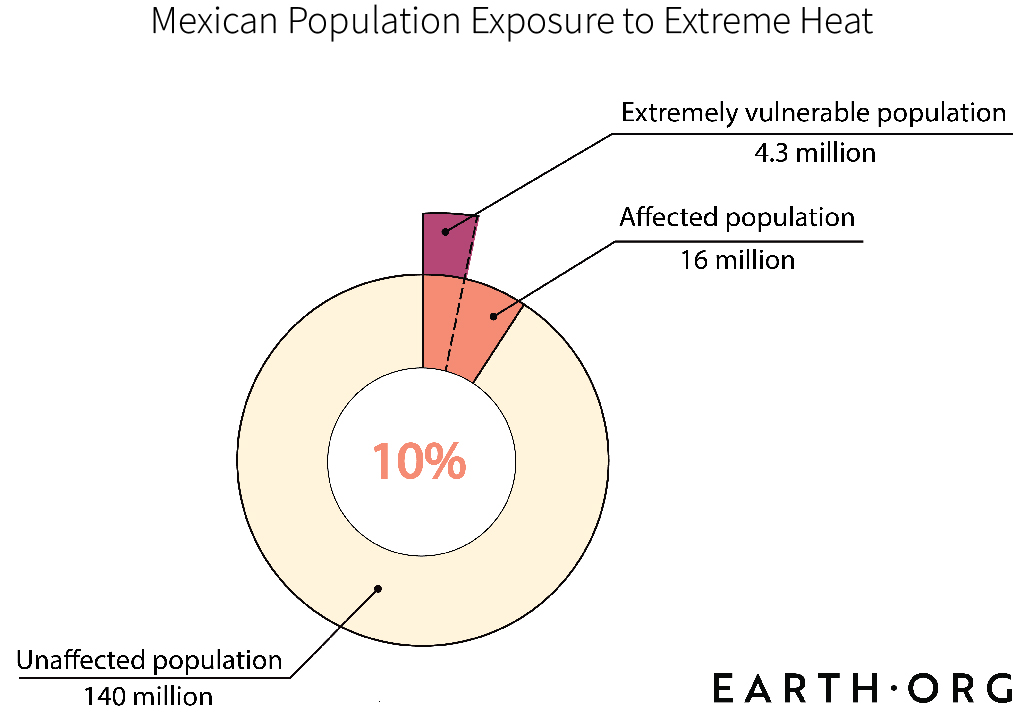

The proportion of Mexicans exposed to MATs above 29°C is low, but still represents 16 million people, 4.3 million of which are in rural or otherwise underdeveloped areas and could lack access to air conditioning. Beyond coping with the heat, large food producing regions will have to massively invest in infrastructure and heat-resistant crops if they are to endure.

Faced with such heat, there are two choices: endure and adapt, or leave. Extreme cases like Mecca push the definition of what can be tolerated, and one could picture a world where we learn to live in extreme conditions. The question is, can we do so within the next few decades? Exodus on the other hand, may simply be the necessary choice in many, if not most cases. How we deal with the 1 to 3 billion climate migrants the unbearable heat could produce is another question.

This article was written by Owen Mulhern. Mapping by Simon Papai.

You might also like: Will it Become Too Hot To Live In Colombia?

![The Statistics of Biodiversity Loss [2020 WWF Report]](https://u4d2z7k9.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/lprwinkyTHB-544x306.jpg)