Off the southern coast of California, the Channel Islands consist of eight islands surrounded by the Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary (CINMS). It is a unique place for rare species, sensitive habitats, historic shipwrecks and a successful example of no-take zones.

Earth.Org takes a closer look.

—

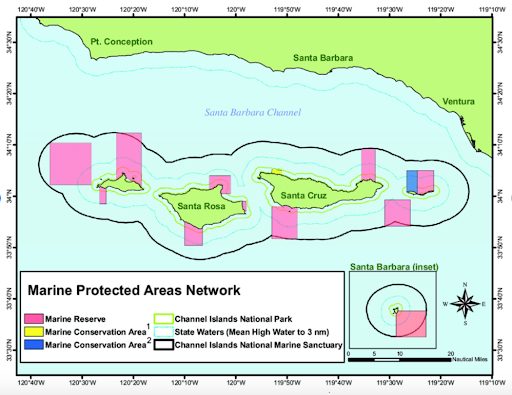

The beginning of Channel Islands’ Marine Protected Area (MPA) can be traced back to 1980, where only a patch of marine boundary around Santa Barbara Island was protected by CINMS. In 2006 and 2007, the Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary (CINMS) adopted 11 new “no-take” State Marine Reserves (SMRs), which do not authorize any activities related to marine resources exploitation. In total, the CINMS now consists of 13 MPAs of which 11 are “no-take” areas.

Fig 1: Channel Islands MPA Network Reference map. Pink areas denote the “no-take” marine zone.

Similar to other “no-take” areas around the world, the 11 SMRs are regarded as so-called “private properties” where any kind of marine resource harvesting is prohibited. This includes both commercial and recreational take. Fishermen who wish to exploit marine resources in the scope of Channel Islands can only go to designated marine conservation areas, where harvesting is allowed under a certain degree of restriction. In spite of the rigorous no-take policy, tourist visits to the zone are still tolerated.

So how effective are these marine reserves?

Eumetopias jubatus, commonly named the Steller Sea Lion, had a catastrophic population drop of 70% between 1970 and 1990. After being declared endangered, the implementation of the no-take zone allowed them to bounce back at a rate of ~2% per year. Thanks to great efforts by conservationists and scientists, they’ve been officially declared as recovered since 2013.

Another example is the Megaptera novaeangliae, also known as the humpback whale. Although they are not based in offshore California, their migration patterns lead them through the Channel Islands periodically. They’ve gone from “endangered” to a less extreme “threatened” since the implementation of the sanctuary.

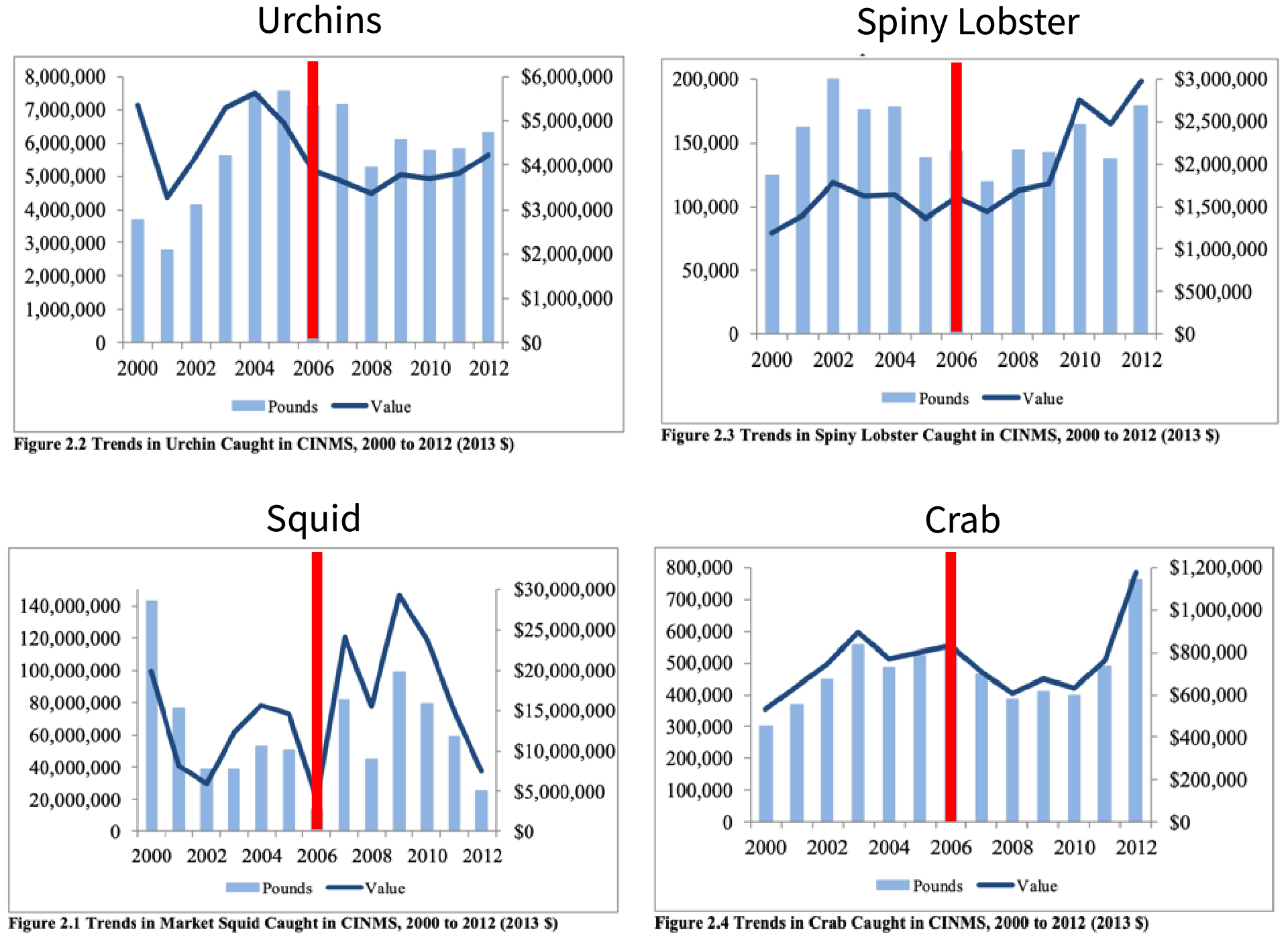

Beyond protecting natural habitats and resources, no-take zones are shown to provide net economic benefits to humans as well. Out of the 4 most sought-after species in the area (squid, urchin, spiny lobster and crab), three have had a net gain in value since 2006-2007. The only species with a downtrend on both caught quantity and value was market squid. According to the report, California market squids are highly vulnerable to El Niño. In La Niña phases, yield seems to bounce back.

Fig 3: Trends of quantity caught and value generated by the top four species in the Marshall Islands Marine Sanctuary. Red lines on the year of implementation of the 11 SMRs (no-take zones).

The only species with a downtrend on both caught quantity and value was market squid. According to the report, California market squids are highly vulnerable to El Niño. In La Niña phases, yield seems to bounce back.

Overall, it is arguably that the establishment of SMRs marks the success in restoring wildlife abundance and sustaining fishing activities. However, the unpredictable effect of climate change has caused serious damage to it. CINMS has released a new Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary Condition Report with a detailed assessment on the islands’ ecosystem quality. Their next step is to identify high priority sanctuary management actions to further protect the precious marine life.

This article was written by Eric Leung. Photo by Danielle Guyder on Unsplash

You might also like: Extreme Temperatures – Part III: Canada

References

-

Marine Reserves, Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary:

https://channelislands.noaa.gov/marineres/

-

Southern California Marine Protected Areas, California Department of Fish and Wildlife:

https://wildlife.ca.gov/Conservation/Marine/MPAs/Network/Southern-California#29097813-marine-protected-areas

-

Steller, National Park Service:

https://www.nps.gov/chis/learn/nature/steller-sea-lion.htm

-

STATE AND FEDERALLY LISTED ENDANGERED (2020).

-

Humpback Whale, National Park Service:

https://www.nps.gov/chis/learn/nature/humpback-whale.htm

-

Economic Impacts on Commercial Fishing, National Marine Sanctuaries:

https://sanctuaries.noaa.gov/science/socioeconomic/channelislands/comm_fishing.html

-

Leeworthy, V. R., Jerome, D. and Schueler, K. (2014) Economic Impact of the Commercial Fisheries on Local County Economies from Catch in the Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary 2010, 2011 and 2012, Marine Sanctuaries Conservation Series.

-

What are El Niño and La Niña? National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration:

https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/ninonina.html

-

Office of National Marine Sanctuaries. 2019. Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary 2016 Condition Report. U.S. Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Office of National Marine Sanctuaries, Silver Spring, MD. 482 pp

-

Mayr, F. B. (2010) ‘Marine protected areas’, Marine Protected Areas, (January 2009), pp. 1–143. doi: 10.4324/9781315624921-9.

![The Statistics of Biodiversity Loss [2020 WWF Report]](https://u4d2z7k9.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/lprwinkyTHB-544x306.jpg)