The famous Great Barrier Reef in Australia is continuously compromised by human activities. To save the last unique piece of marine treasure, the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority (the Authority) partitioned the reef area into color-coded zones to restrict activities. Green zones indicate a “no-take” area where only non-destructive actions are allowed. Significant growth in species abundance and net economy over time convinces its effectiveness.

—

Zoning in the Great Barrier Reef

The Authority announced the Representative Areas Program (RAP) focuses on sustaining biodiversity while maintaining tourism, recreation as well as commercial fishing. The current zoning plan, as part of the RAP process, was introduced in 2004 and it aims to properly structure the usage of different areas in the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park.

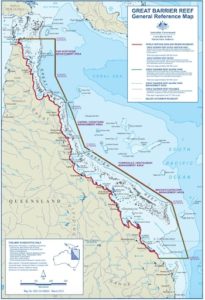

Great Barrier Reef General Reference Map with the boundary of the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park. Source: Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority. Queensland Department of Natural Resources & Mines. Geoscience Australia, National Mapping Division.

Zones are in general divided into eight color codes from light blue to pink. The green “no-take” zone is the second most restrictive zone to the park. According to the Authority, anyone can enter the green zone but only for recreational purposes such as boating, snorkeling and swimming. Any forms of fishing activities, for example spearfishing, is straightly prohibited unless it comes with a permit. Research, depending on the degree of sampling, is allowed without permitting.

Activities guide on different zones in the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park. Source: Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority

Assessing the no-catch zone’s effectiveness

The wide coverage of the fishing forbidden spaces brings back the abundance of some of the prevalent marine species. Let’s take the typical coral trout as an example. After the enforcement of zoning, the species average biomass resulted in a promising 2.5 times increment in the corresponding areas than in open fishing areas.

Coral trout biomass growth from 1996 to 2012. Green and blue circles represent the historical estimates of the species biomass in no-take marine reserves and open fishing areas respectively. Triangles are actual data collected from rezoning surveys (available from 2006). Source: https://eatlas.org.au/nerp-te/gbr-aims-effects-of-zoning

The ecological benefits of the green zones spills over to other areas of the Park. As Mark Read from the Authority adds, “For coral trout, 84% of the larvae produced in the Marine National Park (green) Zone is being exported out to the zones you are allowed to fish in.” Besides quantity, research also shows that green zones cultivate bigger fish which can carry more eggs. This result does not only suggest a rise in the number of broods, but also an increase of species life expectancy.

The Great Barrier Reef Outlook Report from 2009 reviews the economic performance of various activities on the Reef. Commerical fishing and aquaculture saw a big leap after implementation of the zoning system, validating its effectiveness. In addition, a survey with local fishermen reported their satisfaction with no-take zones because of the net yield increase generated, along with wider species variety.

Source: The Great Barrier Reef Outlook Report 2019

Despite the significant revitalisation of some precious marine species, the reef’s health is progressively declining since 2014. The main driver is discovered to be the impact of climate change which brings poor water quality to the reef system.

Needless to say, the Great Barrier Reef is one of the most critical reef systems in the world as it provides habitat for approximately 9000 marine creatures. In a broader angle, the surrounding coral sea also supports over 300 threatened species. As the UN Convention on Biological Diversity proposed a global target in protecting 30% of our land and sea to prevent another mass extinction, the Australian Government and the Authority are seemingly following the right direction to achieve this goal.

This article was written by Eric Leung. Photo by Daniel Pelaez Duque on Unsplash

You might also like: Extreme Temperatures in Indonesia Will be Too Hot to Live In

Reference

-

Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority (2009) The Represenative Areas Program (RAP): Restoring the biodiversity of the Great Barrier Reef.

-

Zoning, the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority

-

Interpreting zones, the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority:

-

Emslie, M. J. et al. (2015) ‘Expectations and outcomes of reserve network performance following re-zoning of the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park’, Current Biology. Elsevier Ltd, 25(8), pp. 983–992. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.01.073.

-

Evans, R. D. and Russ, G. R. (2004) ‘Larger biomass of targeted reef fish in no-take marine reserves on the Great Barrier Reef, Australia’, Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems, 14(5), pp. 505–519. doi: 10.1002/aqc.631.

-

Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority (2009) Great Barrier Reef Outlook Report 2019.

-

Long Term Reef Monitoring Program (2019) Annual Report on Reef Condition: Mixed bill of health for the Great Barrier Reef. Available at: https://www.aims.gov.au/reef-monitoring/gbr-condition-summary-2018-2019.

-

Climate change, the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority

-

Report of the open-ended working group on the post-2020 global biodiversity framework on its second meeting (2020).

![The Statistics of Biodiversity Loss [2020 WWF Report]](https://u4d2z7k9.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/lprwinkyTHB-544x306.jpg)