Dry lighting in August 2020 ignited a series of wildfires across California, scorching the earth in the process and leaving a train of ecological and structural destruction in its wake. The resulting threat to ground stability can leave a long-lasting hazard behind, which authorities must be wary of.

Earth.Org takes a closer look.

—

Source: NASA earth observatory.

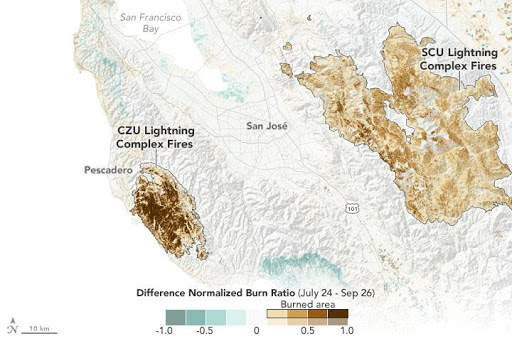

The above map uses near and shortwave infrared data collected between July 24 and September 26th, 2020, to track changes in the landscape’s green spaces. The bar at the bottom measures the severity of the burns.

Source: NASA earth observatory.

This second image shows the same map in natural color. Here we can see the full extent of the damage caused by the CZU Lightning Complex fires in particular, as it shows the stark contrast between the scorched brown area versus the surrounding greenery. Huge swaths of vegetation have been lost in this region.

The SCU Lightning Complex fires are historic in size, burning approximately 825 square kilometers of forest and grassland area between August 18 and October1, making it the third largest fire in California history. The CZU lighting fire complex was comparatively smaller but far more destructive given its location, destroying at least 1,409 structures in just under a month. Ordinarily, California only sees one such large lightning fire complex per year; the SCU and CZU are the 9th and 10th in 2020 alone. Lighting fires are not directly caused by climate change, but they are greatly exacerbated by it: summer heat waves dry out the land, making the area more susceptible to lightning ignition.

What do these images tell us?

These images reveal that a significant portion of land vegetation has been burned away, weakening the structural integrity of the area. The root systems of plants and trees act as stabilizers to the ground underneath by creating a network of interlocking anchors in the soil and loose rocks. Additionally, vegetation balances water saturation in the soil by absorbing some of the water.

With these natural defenses burned away across vast areas of California, the region is at heightened risk of further damage and destruction after the fires subside. Once the fires go out and winter rains arrive, runoff on sloped landscapes will not be well absorbed. With much of the water staying above ground and little to no vegetation blocking its path and slowing it down, the high velocity of the water will be more likely to pick up larger debris, contributing to devastating mudflows and landslides.

These images give geologists and land and forest managers a detailed account of where the fires have caused the most damage. They can then use this information to develop a targeted plan of action to mitigate the risk of mudflows and landslides and minimize their potential damage.

This article was written by Lola Robinson.

You might also like: Extreme Temperatures in Indonesia Will be Too Hot to Live In

References

-

Carlowicz, M. (2020, October 15). Assessing California Fire Scars. Retrieved from https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/147374/assessing-california-fire-scars

-

Fountain, H. (2020, September 18). Oregon Rain Brings New Threat After the Fires: Landslides. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/18/climate/oregon-rain-fires-landslides.html?auth=login-email&login=email

-

Ross, E. (2020, September 18). Why a blast of rainfall on Oregon’s new forest fire scars could trigger landslides. Retrieved from https://www.opb.org/article/2020/09/18/oregon-wildfires-landslides-soil/

-

B.C. Ministry of Forests and Range. (2011). Landslide and flooding risks after wildfires in British Columbia. Wildfire Manag. Br., and For. Sci. Prog., Victoria, B.C. Retrieved from www.for.gov.bc.ca/hfd/pubs/Docs/Bro/Bro91.htm

![The Statistics of Biodiversity Loss [2020 WWF Report]](https://u4d2z7k9.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/lprwinkyTHB-544x306.jpg)