Droughts and heatwaves are both damaging, costly phenomena, but their effects are compounded when they coincide. The United States suffered three of these devastating dry-hot extremes between 2011 and 2013, tallying up US $60 billion in damages. Worse yet, they are becoming more likely.

Earth.Org takes a closer look.

—

The US has been in the grips of a megadrought for the past 20 years, putting strain on water reserves and providing dry fuel for wildfires. To make things worse, a scorching heat wave is baking the West Coast and most of Texas, combining with the aridity to stoke the worst wildfire season in memory.

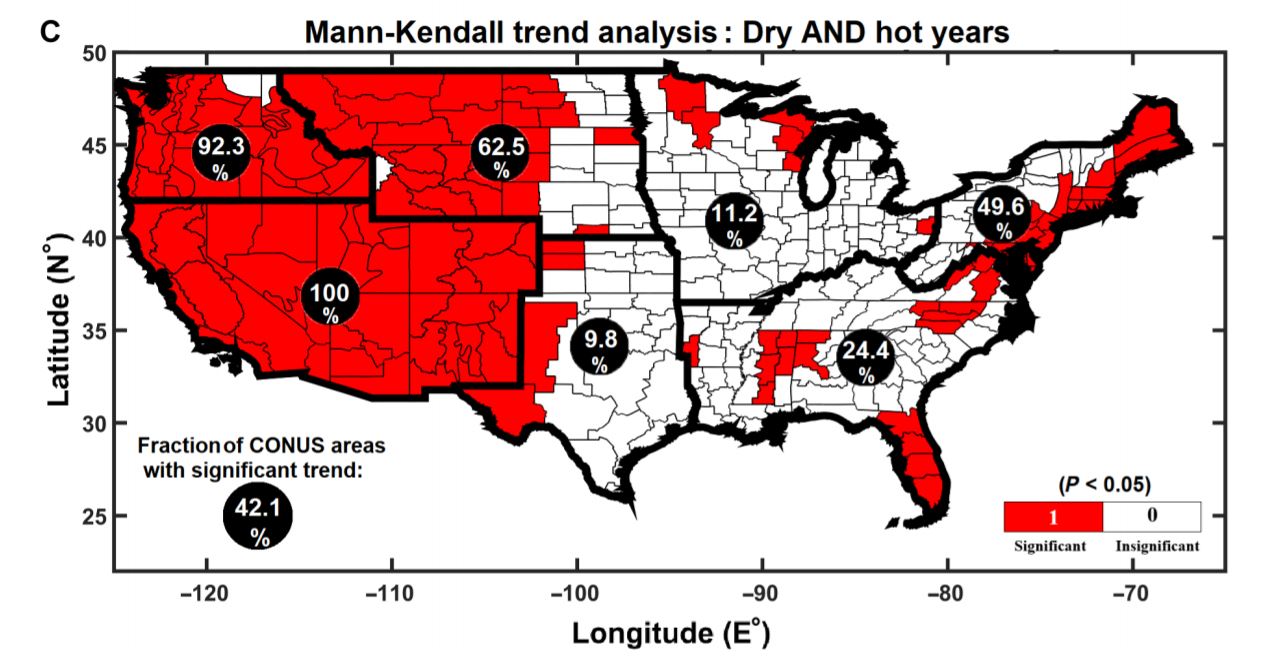

As droughts persist and heatwaves multiply, we can expect these to coincide more often. Compound dry-hot extremes are extremely costly, as they put enormous stress on crops, water reserves, infrastructure (think electrical grids), all while making wildfires more likely. A study published in Science Advances (Reza Alizadeh et al. 2020) used over a century of data over the United States (US) to analyze the changes in coinciding drought and heatwave events. Their results show a significant increase in both the frequency of concurrence, but also in the area at risk.

Red shaded areas show a significant increase in the likeliness of concurrent hot and dry extremes over the past 122 years (1896-2017).

The occurrence of the dry-hot years jumped up noticeably between 1993-2017 when compared to the 1943-1992 period. In other words, things have been getting worse in the last three decades.

Usually, these compound extremes are caused by precipitation deficits as was the case during the decade-long 1930s drought. However, the authors found a shift from lack of rainfall to excess heat as a dominant driver, which is at least partly driven by anthropogenic global warming.

According to the authors, the feedback loops responsible for generating weather extremes are beginning earlier, covering broader swathes of the country and creating stronger feedback loops, intensifying the likelier dry-hot extremes.

The evidence is right in front of us, with the hellish wildfires devastating the states of California and Oregon, worsened by fire-stoking winds but hopefully dwindling soon. Right?

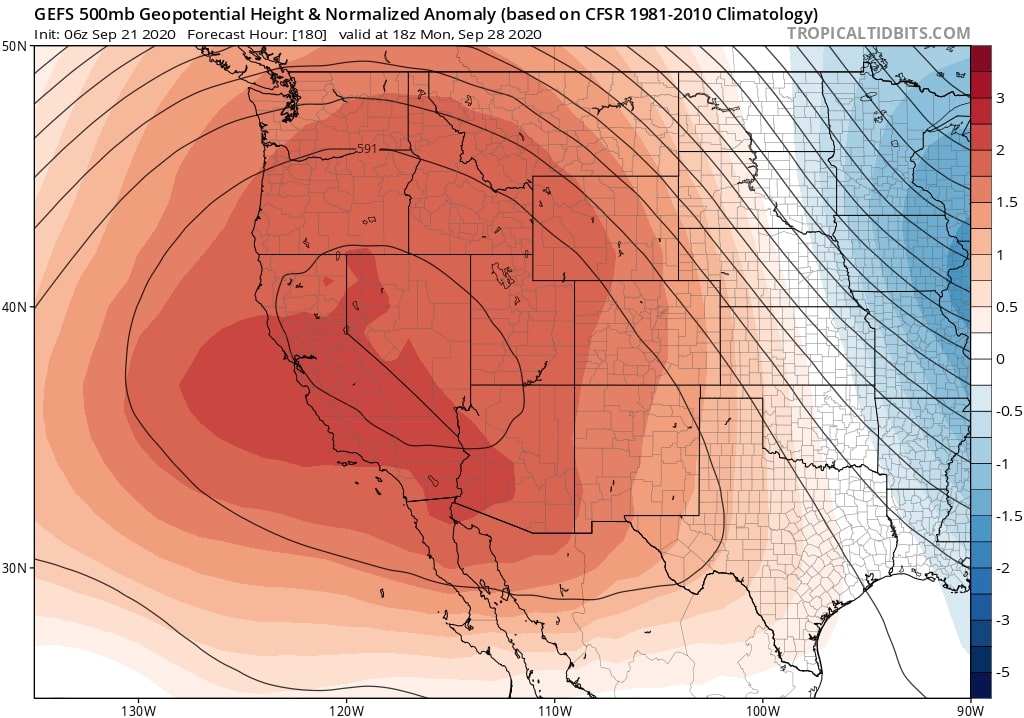

Well, not quite. As we know, the US drought isn’t going anywhere, so the focus is on the next heatwave. Daniel Swain, a climate scientist at UCLA, warns us of incoming “ridges”, or areas of high atmospheric pressure that prevents rain and cloud formation, usually inducing a heatwave.

Source: Daniel Swain, @Weather_West.

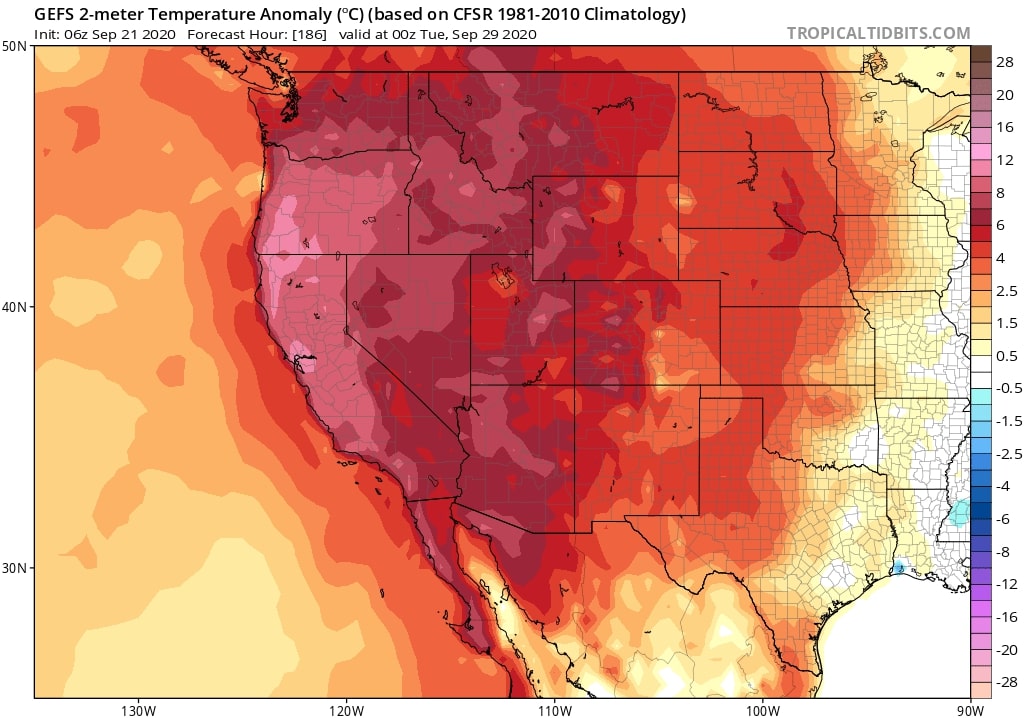

These images were generated with a multi-model ensemble and depict the high pressure meant to occur by early October. Pressure patterns are one thing, but how do we expect this to affect temperature? Mr. Swain provided us with another map, and it doesn’t look good.

According to these results, the worst is yet to come. Of course, there is always uncertainty when modelling weather, and we can only hope for the heatwave projected above not to be so harsh. Either way, California will bounce back and hopefully implement better forest and fire management. The only question is: how many more records need to be broken before we truly start decarbonizing our society?

This article was written by Owen Mulhern.

Photo by Anton Ivanchenko on Unsplash

References

-

A century of observations reveals increasing likelihood of continental-scale compound dry-hot extremes. BY SCIENCE ADVANCES

![The Statistics of Biodiversity Loss [2020 WWF Report]](https://u4d2z7k9.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/lprwinkyTHB-544x306.jpg)