- Population (2021): 105,044,646 (ranked 15th globally)

- GDP per capita (2021): US$ 588 (ranked 205th out of 213 globally)

- Emissions (2016): 6.56 million tonnes (ranked 119th globally)

Pledges & Targets

- Paris Agreement & NDC: The Democratic Republic of the Congo’s (DRC) Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC), last updated in December 2017 targets the following:

-

-

- Reducing emissions by 17% compared to business as usual (BAU) by 2030.

- The DRC NDC does not specify what baseline year BAU refers to

- Adapt and develop local and regional economies to handle the localised effects of climate change

- Reducing emissions by 17% compared to business as usual (BAU) by 2030.

-

- Energy Goals: The DRC seeks to achieve 100% renewable energy usage by 2050

- Conservation Goals: Expand existing forest coverage by 3 million hectares by 2025

State of Affairs

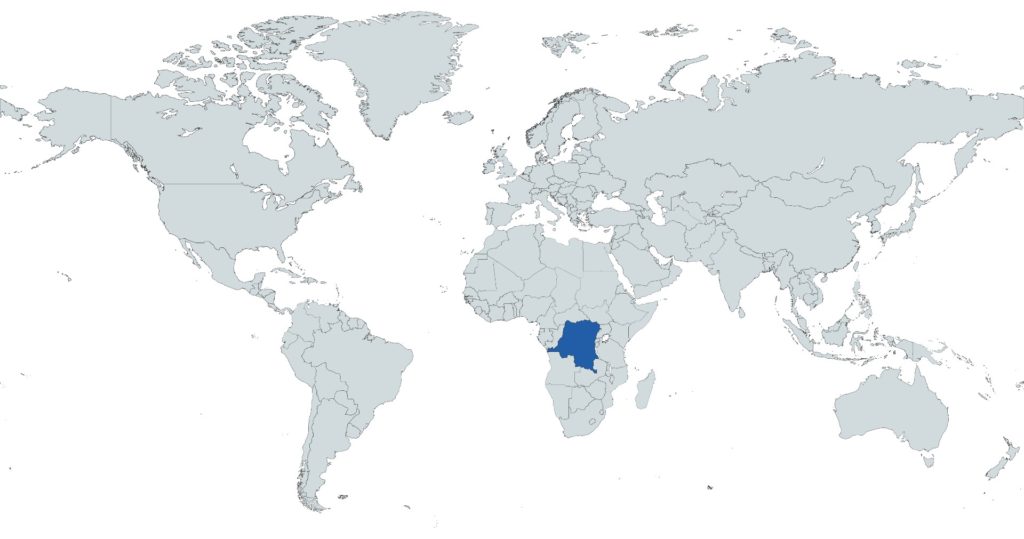

The DRC is the 2nd largest country in Africa by land area after Algeria, and the largest country in Sub-Saharan Africa. The landscape of the DRC is dominated by the dense Congo Rainforest, covering over 50% of the country. The Congo Rainforest is the 2nd largest rainforest in the world, after the Amazon, and one of the planet’s vital natural carbon sinks, potentially holding 30.6 billion metric tonnes of carbon.

The DRC has experienced massive population growth over the last decade. In 2010, the population was 64.6 million. In 2020, it was 89.6 million, and in 2021, the population had grown to 93.2 million. That amounts to a 28.6 million-person increase over the past 11 years. The DRC has an extremely low GDP per capita, both in nominal and purchasing power parity (PPP) terms. The DRC’s nominal GDP per capita was ranked 205 out of 213 countries globally, and their PPP was ranked as 222nd out of 225. According to the World Bank (2014), the DRC was ranked as the 49th most unequal country in terms of income (of 159 countries), and 66th (of 172) for wealth inequality. Additionally, according to the 2020 Human Development Report (HDR) published by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), the DRC had a Human Development Index (HDI) of 0.480 out of a possible 1.00, which is classified as low. The Inequality-adjusted HDI was even lower, with a score of 0.335.

According to the CIA Factbook, the DRC’s agricultural sector accounted for 19.7% of the total GDP, the industrial sector made up 43.6%, and the service sector generated 36.7%. The percentage of the Congolese workforce employed by each sector was unavailable, likely due to the DRC’s difficulties in conducting censuses. As of 2019, the DRC has not conducted a census for over 30 years. This lack of information means that it is difficult to gauge the relative effects of climate change on various segments of the population.

The DRC has immense mineral and natural wealth, however the majority of the foreign direct investment (FDI) goes into the mining industry, exacerbating levels of pollution without the mining wealth being redistributed to the Congolese population to raise poverty levels. Approximately 60% of the world’s cobalt comes from the DRC, which has doubled in price since 2015. Despite the fact that the government owns a large percentage of mining corporations in the DRC, the large foreign firms that operate are offered incentives such as minimal capacity for oversight, and other mining rights that attract economic, political, and military interests from neighbouring countries in addition to foreign capital. However, capital accrued from extractivist policies are not being reinvested into the country, as reflected in the levels of poverty, inequality, and corruption.

Due to the DRC’s lack of financial resources and ability to project power domestically, their ability to project enough power for climate initiatives, infrastructure projects, and social programs across the country suffers. The DRC is therefore heavily reliant on foreign financial aid to hit their social and climate targets. However, the DRC stated that they want the UN completely out of the country by 2020, despite the millions of Congolese in need of humanitarian assistance and the dire state of the DRC’s infrastructure. In addition, the presence of armed militias and rebel groups in the DRC presents challenges to the government ‘s ability to implement and enact climate friendly policy and infrastructure projects throughout the country. Therefore, due to this instability, the government has been unable to guarantee safety of investments and stable returns for investors. This has hampered efforts to improve living conditions and build resilience against climate change.

Climate Readiness & Vulnerability

The ND-GAIN Country Index by the University of Notre Dame summarises a country’s vulnerability to climate change and other global challenges in combination with its readiness to improve resilience. The more vulnerable a country is, the lower their vulnerability score, while the more ready a country is to improve its resilience, the higher its readiness score will be, on a scale between 0 and 1. The DRC’s scores are:

- Vulnerability: 0.592 (ranked 176th out of 182 ranked countries).

- Readiness: 0.241 (ranked 175th out of 182 ranked countries).

As per the ND-GAIN Index, the DRC is ranked 178th out of 182 countries for overall readiness and vulnerability. In terms of climate vulnerability, the main areas of concern in the DRC, as per the ND-GAIN Index, are related to the flooding of the Congo River, crop failure and prevalence of infectious diseases. These issues are exacerbated by the DRC’s poor governance and the lack of foreign aid. In terms of vulnerability to damages caused by climate change-related disasters such as floods, droughts, and severe weather patterns there are many areas in the DRC which are under extreme threat. As a result of its history of exploitation and deliberate underdevelopment, the DRC has been economically and politically unable to prepare for climate change. In addition, trends in the Congolese population’s access to electricity as of 2021 is amongst the lowest globally, with only 41% of urban residents and 1% of rural residents having access to electricity. Nationwide, only 19% of Congolese have access.

The DRC’s crop productivity is severely at risk as the country has been unable to modernise its agricultural sector. In conjunction with a relatively low agricultural output, which accounts for only 19.7% of the DRC’s GDP, the DRC has a high prevalence of child malnutrition. Climate change-induced crop failures could therefore exacerbate famine conditions in the country.

Approximately half of Africa’s forests and water resources are in the DRC, yet only 26% of the country’s population has access to clean drinking water. The large Lukaya River Basin provides drinking water for the population of the capital city of Kinshasa, but flash floods and erosion threaten the reservoir’s stability. This deterioration is exacerbated by practices such as slash and burn agriculture, quarrying, and charcoal production.

Deforestation and the consumption of wild bushmeat puts the Congolese population at an increased risk of infectious disease. For example, there was an outbreak of Ebola between 2019 and 2020 in the eastern regions of North- and South-Kivu. This threatens both humans and ecosystems, including plant and animal life.

In addition, climate change-induced droughts increase fire risk, which is exponentially increased in slums due to the close living quarters and presence of flammable building materials. On the other hand, slums are at an increased risk of sustaining damage from flooding. The Congo River also poses a flooding risk. Between October 2019-January 2020, there were intense rainstorms resulting in the landslides and flooding of the Congo River, resulting in over 40 deaths in Kinshasa.

Overall, the DRC’s institutions, economy and its public and social infrastructure is ill-prepared for climate change. According to the ‘Doing Business Index’, which measures the ease and attractiveness of doing business via indicators such as ease of registering property, access to electricity, contracting construction companies and attaining permits, enforcing contracts, and resolving insolvency, as cited by the ND-GAIN Index, the DRC is amongst the lowest globally. The DRC has an economy built upon industrial resource extraction, and with relatively few foreign firms involved, the Congolese government has established a monopoly of poorly administered state-owned institutions and industries.

The governance section of the ND-GAIN Index’s ‘Readiness’ portfolio is unavailable, leading to the interpretation, in conjunction with previously listed information, that the capability of the DRC’s government to fulfil its role is severely lacking. As for the ND-GAIN’s social readiness category, the DRC’s education levels are among the lowest globally, as is their information and communication technology (ICT) infrastructure, largely as a result of extreme poverty and low levels of access to electricity. The factors contributing to a low readiness score are deeply interconnected and they influence each other in a vicious circle.

While corruption under Mobutu Sese Seko (President from 1965-1997) was rampant, it has reportedly been decreasing in recent years. Sese Seko embezzled an estimated US$4 billion in foreign aid, loans, and public funds over the course of his dictatorship, leaving public and social infrastructure neglected. This meant that for nearly 30 years, the extreme corruption in the DRC (on top of historical exploitation) contributed to its lack of development and current lack of readiness to manage the climate change-related disasters.

Environmental Policies by Sector

Energy

- Per IRENA, renewables made up approximately 97% of the DRC’s total final energy consumption in 2018.

- 97% of the renewable energy came from bioenergy.

- The remaining 3% of renewable energy production was sourced from hydroelectricity.

- 3% of energy consumed in the DRC is generated from fossil fuels, mainly oil.

While the DRC is not reliant on fossil fuels, the vast majority of its energy is generated from bioenergy, energy extracted from naturally occurring biological sources, such as grasses and trees, usually by burning them. Bioenergy, while classified as a renewable energy source, is far from ideal, given that burning biomass does still release CO2, albeit less than fossil fuels would, and other harmful greenhouse gases such as methane. The DRC’s reliance on bioenergy is another factor in their high pollution levels, along with industrial operations. Bioenergy comes from biomass or biofuels, which absorb the sun’s energy and store it in chemical form. For example, wood is a commonly used source of bioenergy. While renewable via trees’ natural life and reproduction cycles, burning wood still releases harmful greenhouse gasses that contribute to climate change. In addition, the 3% of renewable energy that the DRC uses per year represents a fraction of the total that they could be producing for domestic consumption and export.

The Congo Rapids near the mouth of the river serve as a barrier to using the full length of the Congo river for transport and trade to and from the Atlantic Ocean. Despite the Congo River serving as a highway for transport and trade within the country, with over 15,000km of navigable waterways, its clean energy development potential is yet to be realised. The Congo River could provide unprecedented amounts of clean and renewable energy to over 1.2 billion people. This is a double-edged sword in terms of climate vulnerability and readiness, however. For example, the damming of the Congo River would flood massive areas of surrounding land, displacing people living in the vicinity and disrupting local and regional ecosystems.

Transportation

- The rate of personal car ownership in the DRC is unequally distributed depending on income level.

- Households earning over US$750/month generally can afford to have a car, while those under that income level overwhelmingly cannot

- Public transit infrastructure is severely underdeveloped and underfunded in the DRC

- There are approximately 15,000km of navigable waterways in the DRC’s Congo River Basin, which is the country’s main transit network

- Railroads and roads serve to supplement the river transit network

As one of the most impoverished countries in the world, with a relatively high level of income and wealth inequality, most people in the DRC cannot afford a personal car. Still, the urban sprawl of Kinshasa generates high rates of pollution and GHG emissions, especially from congested streets and related tailpipe emissions. Poor public transportation networks are often blamed on civil conflict hampering the state’s ability to create infrastructure projects to contract out to private enterprise, but the DRC’s colonial past and extractivist present have made development stagnate.

Under colonial rule by Belgium in the early 20th century, roads and railroads were built using Congolese forced labour, for the purpose of facilitating the process of inland resource extraction and transport to the coastal ports, such as extracted rubber, minerals and metals retrieved from interior mining sites. Therefore, transportation networks were built, but these were poorly managed and have barely been modernised. These rudimentary rail and road systems are notoriously dangerous, which further incentivises people to use the vast river system as their primary means of transit. This contributes to the pollution of the river due to emissions and leakage from boat motors.

Accidents resulting in the sinking of ships are also common on the Congo River, releasing oil and other chemicals into the water. This water then flows towards the Atlantic Ocean, polluting the local inhabitants’ drinking water, ecosystems, and groundwater along the way. Toxic waste from mining operations also contribute heavily to pollution in the Congo River. For example, in August 2020, an industrial diamond mine in northwestern Angola released an unspecified toxic waste that turned the Kasai River, a tributary of the Congo, red. The toxins were nearly carried as far as Kinshasa.

Anthropogenic pollutants also enter the Congo River from rivers in the Upper Congo Basin such as the Lumami and Lualaba. This becomes very serious in the Congo River Floodplains near Kinshasa, when contaminated water flows into surrounding bodies of water. The danger of this is exacerbated by the fact that the Kinshasa city aquifer connects to these other water sources, such as swamps.

Biodiversity

- The DRC has the highest biodiversity in Africa for all categories of species with the exception of plants

- As per the NGO Protected Planet:

- 13.83% of the DRC’s land area is protected as of 2021

- 0.24% of the DRC’s marine area is protected as of 2021

- Per the Yale Environmental Performance Index, 45.64% of the DRC’s population is urbanised.

- Yale EPI ranked the DRC 87th in the world in terms of ecosystem vitality, which measures how well countries preserve, protect, and enhance their ecosystems and the services they provide.

- Per Global Forest Watch, the DRC possessed 198 Mha of natural forest, extending over 85% of its land area. By 2020, the DRC had lost 1.31 Mha of natural forest.

There is a very high degree of biodiversity in the DRC. According to the African Wildlife Foundation (AWF), the DRC is home to over 400 species of mammals, 400 species of fish, 1,000 species of birds, and 10,000 species of plants. The state of biodiversity is currently under threat from industrial mining, deforestation, slash-and-burn agriculture, hunting for bushmeat, and illegal poaching. The DRC has confirmed their commitment to REDD+, a UN project which seeks to reduce emissions from deforestation and forest degradation by implementing a sustainable forest management approach with an emphasis on including all stakeholders in decision-making processes. However, this contradicts their directive to UN personnel to leave the country by 2020, making the validity of their commitment questionable. International observers have also attributed high rates of deforestation in the DRC to the country’s poor governance.

Wildlife

- As of 2013, the DRC had 314 species listed as threatened (either vulnerable, endangered, or critically endangered)

- According to the African Wildlife Foundation, the DRC is home to 3 out of 7 (8, including humans) species of great apes

- There is an extreme danger posed by wildlife poachers, and armed rangers, in part employed by NGOs, are needed to combat this threat

Deforestation, hunting for bushmeat, and illegal poaching poses a serious threat to the DRC’s over 1,800 species of wildlife. According to the AWF, the great ape population in the DRC is expected to decline by 50% by 2078. Forest elephants are also at risk of poaching and habitat loss. To combat this, the DRC employs armed rangers in wilderness areas to combat illegal poaching operations, and has nominally protected national park areas. Pangolin, porcupine, okapi, crocodile, and monkey meat are commonly sought after sources of bushmeat, and are being hunted in increasingly unsustainable ways.

Pollution

- Per the International Association for Medical Advice to Travellers (IAMAT), in 2020 the DRC averaged 45 µg/m³ (micrograms of air pollutants per cubic metre of air), which exceeds the maximum healthy level of 10 µg/m³.

- Congolese cities as a whole are deemed to have poor levels of air quality, although discrepancies exist between the densely populated and urbanised cities such as the capital Kinshasa and the less-developed regions throughout the DRC.

Pollution stemming from industrial activities in the DRC affects the surrounding environment with various forms of waste and emissions. According to USAID, the main sources of emissions in the DRC are the burning of biomass (80.1%), followed by agriculture (9%). Industrial processes account for 0.1% of emissions. Some skepticism is needed, as many mining operations are conducted illicitly. However, sources of pollution from mining are not limited to greenhouse gas emissions. Disposal of toxic waste into nearby bodies of water, for example, has far-reaching implications for surrounding ecosystems. For example, the industrial diamond mine spill that turned the Congo River red in August 2020 disrupted ecosystems by killing threatened species of Hippopotamus.