- Population (2020): 540,542 (ranked 173rd globally)

- GDP per capita (2020): USD 7,456 (ranked 80th globally)

- Emissions (2019): 1.67Mt

Pledges & Targets

- Paris Agreement & NDC: The Maldives’s Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC), last updated in December 2020, targets the following:

- The Maldives is targeting an emission reduction rate of 26% by 2030.

- Road to Net-Zero: Should the Maldives receive adequate international support, assistance and financing, the government announced in its NDC that its emission reduction pledge could conceivably become a 2030 net-zero target.

State of Affairs

After updating its NDC in December 2020, The Maldives government provided some follow-up information to demonstrate its environmental commitment towards 2030.

The Maldives’ NDC aims to slash 26% of their carbon emissions by 2030 with adequate international support and assistance, which would address technology transfer, capacity building and availability of financial resources. This target is in relation to a business-as-usual (BAU) 2030 scenario, using 2011 as the base year of emissions. Although the Maldives’ GHG emissions represent only 0.003% of global emissions, the country is highly vulnerable to the effects of climate changes, according to the 2020 ND-GAIN Index, which ranks the climate adaptation performance for 181 countries. In light of this, the Maldives’ government believes that they should act as a role model to achieve a transformational economic and environmental path to fulfil net-zero targets by 2030. In particular, the updated NDC mentions that the Maldives will develop a detailed plan with the consultation of development partners, donors and other stakeholders to map out the net-zero pathway by 2030.

The Maldives has opted to focus on adaptation instead of mitigation because temperature rise above 1.5C, which according to the latest IPCC report is very close to being locked in, will have a direct and severe effect on the country, as sea-level rise threatens the long-term habitability of low-lying island countries such as the Maldives. The Maldives is therefore evaluating solutions to adapt to climate change’s effects, rather than reduce its emissions which are already minimal relative to the rest of the world. The adaptation actions include coastal protection, safeguarding coral reef biodiversity, revenue from tourism, early warning and systematic observation and disaster risk reduction and management. Although the Maldives aims to establish the National Adaptation Plan (NAP) with short, medium and long-term adaptation programs, very little progress has yet to be made.

Despite the Maldives having an ambitious plan and being on track, the financial ability is dragging Maldives’ back due to an enormous investment and operation cost. Even though the Maldives wishes to update its NDC plan and shape itself as a role model, its economy may hold it back. According to a 2016 financial estimate, the country needs around USD$8.8 billion in total to shield all of its inhabited islands from sea level rise. In spite of receiving nearly $24 million in financial aid from the United Nations, environment minister Hussain Rasheed Hassan urges developed countries to lend a helping hand or the country will disappear in the following decades. In short, there remains a huge question of whether Maldives’ ability can accomplish its vision without international assistance.

Climate Vulnerability & Readiness

The ND-GAIN Country Index by the University of Notre Dame summarises a country’s vulnerability to climate change and other global challenges in combination with its readiness to improve resilience. The more vulnerable a country is, the lower its vulnerability score, while the more ready a country is to improve its resilience, the higher its readiness score will be. The Maldives’s scores are:

- Vulnerability Score: 0.493 (ranks 129th out of 192 countries)

- Readiness Score: 0.422 (ranks 86th out of 192 countries)

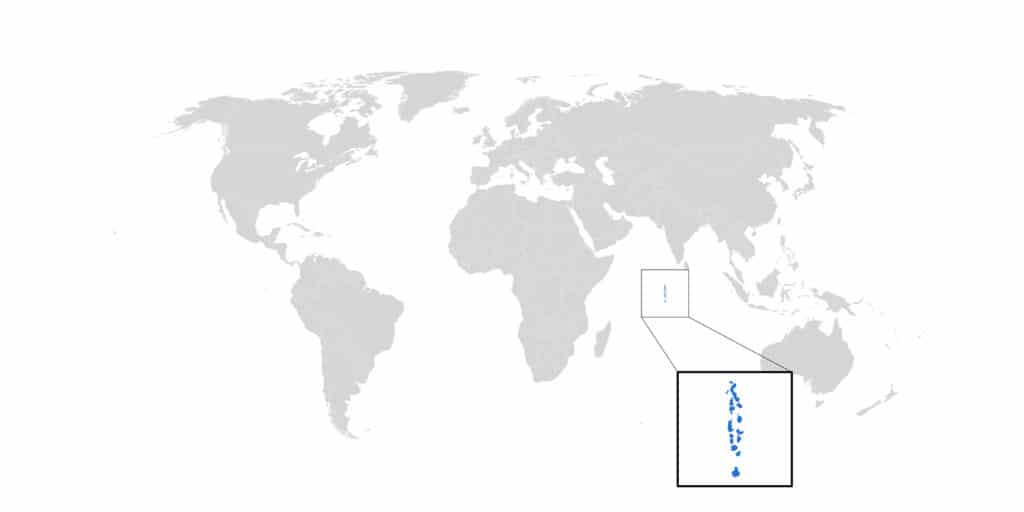

Like most low-lying island countries, the Maldives is under severe threat from sea-level rise and may disappear by the end of the 21st century if emissions continue to rise. ⅘ of the country’s 1,190 islands are merely one meter above sea level and are all severely vulnerable to rising sea levels. Aminath Shauna, the Maldives’ Minister of Environment, Climate Change and Technology, once anticipated that the entire country “will not be here” by 2100 if the global sea level keeps rising 3 to 4 mms annually. Low-lying islands might become uninhabitable by 2050 as wave-driven flooding becomes more common than nowadays. 90% of the islands experience flooding, 97% of them are suffering from shoreline erosion and 64% of them are confronting serial erosion.

In 2008, former president Mohamed Nasheed, even considered purchasing land in Australia for Maldives citizens as an insurance policy for the worst-case scenario. To tackle this ongoing environmental crisis, the Maldives has already adopted coastal protection tools and community programs to encourage national resilience and minimise the effects of climate change. The country also wants to shape itself as a “leader in mitigation efforts” to raise public awareness across the globe. However, an endless socio-political upheaval, corruption and abuses of power hinder the feasibility of the country’s promises. The Maldives has been more proactive than most in tackling rising sea levels through resilience and adaptation measures, but given the country’s extremely low share of global emissions, its survival ultimately depends on international collaboration.

Drought is also threatening the survival of the Maldives due to unpredictable rainfall and sea-level rise. In 2010, 77% of Maldivians heavily relied on rainwater for drinking, so an improvement of the water system to survive drought conditions is desperately needed. In response, the UN Development Programme (UNDP) has been working with the Adaptation Fund, which was executed by the Ministry of Environment and Energy of the Maldives, to offer $8.9 million for the integrated water resources management programme. The programme has three solutions: rainwater, groundwater and desalinated water. According to a GCF press release in 2017, the project promises to deliver safe freshwater to 105,000 people by 2022, which will cover nearly ⅓ of the country’s population. In short, water resources have become a challenging aspect of the survival of the Maldives due to rapid climate change.

Environmental Policies by Sector

Energy

- Renewables made up 1.2% of Maldives’s total energy share in 2017, per IRENA.

- Between 2012 and 2017, the share of renewable energy in Maldives’s renewable energy supply grew by 29.5%.

- In 2017, fossil fuels accounted for 99% of Maldives’s energy production. Renewable energy, such as bioenergy, accounts for 1%.

The government of Maldives has promoted an official roadmap to replace traditional fossil fuels with renewable energy by 2030. As 99% of the Maldives’ energy consumption in 2018 derived from oil, the country is targeting to raise the share of renewable energy in the energy mix from 20% by 2023 to around 70% by the end of the decade, mainly focusing on expanding solar energy capacity. To achieve this ambitious goal, the government launched a five-megawatt solar project in 2020 with external help from the World Bank-funded Accelerating Sustainable Private Investments in Renewable Energy project to lean one step closer to its eventual renewable energy targets. What’s more, the world’s largest solar power plant at sea with 678kWp was established at Maldives resort in 2019.

The country has signed a power purchase agreement (PPA) with Thailand-based company Ensys Co. Ltd to lay solar grids at the sea bridges that connect the capital Male, the main airport and a satellite town. According to the PPA, the cost of a kilowatt-hour is down to US $10.9 cents in comparison to the most efficient technology for diesel which costs between USD$23-$33 cents. Although solar energy offers a relatively cheap electricity cost, the government is also relying on private sector investment by displaying a high level of market confidence to alleviate its financial burden as a high investment cost is inevitable. Nonetheless, the aforementioned electricity costs can lower the total cost of electricity service, fuel import bills and slash carbon emissions.

Transportation

- On islands, private vehicles are the primary mode of transportation, with little in the way of land-based public transportation.

- Tourists visit remote islands by boats and seaplanes. About 80% of tourists prefer seaplanes.

- Passenger ferries up to 10knots, traverse most islands. Passenger ferries up to 20 knots are used to connect the airport to resorts.

Transportation is an insignificant sector in the Maldives due to its country size. Yet, the government has advocated environmentally sustainable vessels to emit less GHG emissions. Also, the government launched “no vehicle days” to alleviate air pollution caused by increasing numbers of vehicles and traffic congestion.

As seaplanes are the pillars of the Maldives’ tourism, the country welcomes an environmentally friendly transportation system to achieve zero-carbon tourism in response to their NDC goal by 2030. 13 MEng Aeronautical Engineering are finalists from Loughborough University who are working on an all-electric, low-emission seaplane which can be applied to tourism and medical sectors at the same time. If this becomes a reality, then the government would adopt this innovative technology to alleviate GHG emissions as an environmental contribution.

Biodiversity

- 2.3% of the Maldives’s territorial space is protected, and 0.07% of the Maldives’s marine seas are considered Marine Protected Areas.

- Per Yale’s Environmental Performance Index, 40.67% of the Maldives’ population is urbanised.

- Yale EPI ranked the Maldives 177th in the world in terms of ecosystem vitality, which measures how well countries preserve, protect, and enhance their ecosystems and the services they provide.

- According to the World Bank collection of development indicators, forests covered 2.73% of the Maldives’s land in 2018. In 2010, the Maldives had 2.79 Kha of natural forest, extending over 10% of its land area. From 2002 to 2020, the Maldives lost 13ha of humid primary forest, making up 23% of its total tree cover loss in the same time period.

The Maldives archipelago is surrounded by the Indian Ocean with abundant marine biodiversity. As 1,192 coral islands form 26 natural atolls, the tropical country is rife with vibrant coral reefs, providing ideal ecosystems for extremely diverse flora and fauna. The Maldives has two of the largest natural atolls in the world: Thiladhunmathi Atoll with a total surface area of 3,788 km and Huvadhoo Atoll with a total surface area of 3,278 km. This coral reef system is the 5th most diverse ecosystem of the world’s reef area and covers an area of approximately 8,900km2. In particular, the Maldives has over 1,100 species of demersal and epipelagic fish, including sharks, 5 types of marine turtles, 21 species of whales and dolphins, 180 species of corals and 400 species of molluscs. There are over 120 species of copepods, 15 species of amphipods, over 145 species of crabs and 48 species of shrimps. There are also 13 species of mangroves and 583 species of vascular plants. In short, biodiversity is the livelihood of the Maldives. 98% of national exports, 62% of foreign exchange and 71% of national employment are highly related to biodiversity.

However, tourism, over-exploitation, waste pollution and land reclamation are threatening biodiversity. In response, the government has banned coral mining, turtle and shark fishing within its territory. What’s more, the Maldives’ Ministry of Environment and Energy executes the National Biodiversity Strategies and Action Plans to stimulate ecological sustainability, individual responsibility for biodiversity conservation, equitable sharing of benefits, accountability and transparency of decision-makers to the public and various community participation. To fulfil 2020 Aichi Biodiversity Targets, the Maldives’s Environment Protection and Preservation Act 4/93 displays 44 protected areas, covering 428,569 hectares of marine area nad 273 hectares of land area. Also, the Maldives has been supporting national implementation, including legislation, funding, capacity-building, education and coordination with private sectors.

Wildlife

- Per the global NGO Earth’s Endangered Creatures, the Maldives possesses 129 endangered species, of which 0 are plant species and 129 are animal species. Most of the Maldives’ endangered fauna are species of coral.

The government of Maldives passed an Environmental Protection and Preservation Act on 19th April 1993. According to the Act, the Ministry of Planning and Environment should identify protected areas and formulate regulations. Also, any type of wastes, oil, poisonous gases that may cause environmental effects, shall not be disposed of within the territory or offenders would be fined not more than Rf100,000,000.00 (around USD$6.5 million) depending on the seriousness of the offence. According to the Act, a person commits an offence if he negligently:

- Cruelly mistreats animals

- Neglects an animal in his custody, then this offender will be imprisoned for not more than 3 months.

Pollution

- The Maldives has none of the PM2.5 concentrations that would be considered above the WHO’s recommended exposure range.

- In 2019, the Maldives had on average 1.8kg of waste per capita in Male, 0.8 kg per person per day on other inhabited islands, and 3.5kg per person per day in resort islands while the country generated around 365,000 tons of solid waste annually.

The Maldives suffered the highest levels of marine plastic pollution in their history last year. Most of them are microplastics with less than 5mms longs so they are considered invisible water pollutants. The researchers elaborated that these little pieces could come from plastic bottles, textiles and clothing and it is slowly disintegrating in the Indian Ocean. This marine plastic pollution can be traced back to neighbouring countries, such as India, Sri Lanka and Bangladesh because they have unsatisfied sewage management and wastewater systems. What’s more, Professor Burke Da Silva of Australia’s Flinders University has pointed out that the domestic waste management system is confronting a challenge as population growth and national development are increasing at least 58% of waste generated per capita on a local island in the previous decade.