The Great Pacific Garbage Patch is a colossal collection of marine plastic waste and debris located in the North Pacific Ocean and is formed by the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre.

—

Sea plastic pollution is one of the most pressing environmental problems the world currently faces right now. According to a study published in the science journal Nature, about 11 million tons of plastic enter the world’s oceans every single year, severely harming marine habitats and the animals that live in them.

But the ongoing problem of marine debris – which encompasses materials including marine plastic waste, fishing nets and gear – is nowhere more evident than the existence of the Great Garbage Patch, which is estimated to be a staggering 1.6 million square km in size.

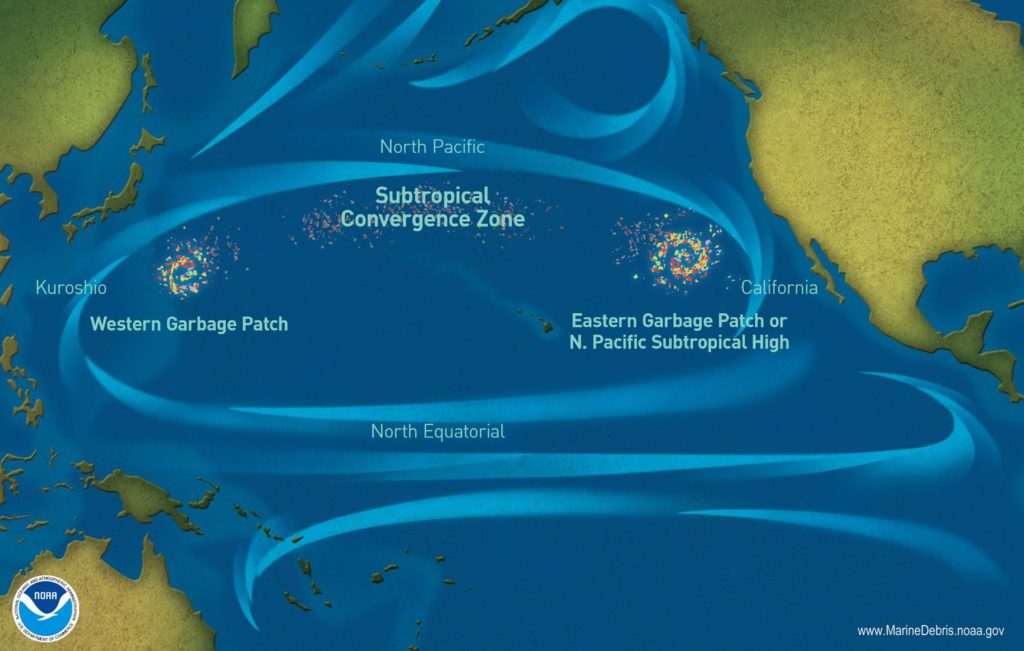

The Great Garbage Patch, however, is not one single pile of trash in the ocean. but rather refers to two distinct collections of marine plastic waste formed by the massive North Pacific Subtropical Gyre.

How is the Great Garbage Patch Formed?

There are two distinct collections of marine debris that make up the Great Garbage Patch. The most notable collection spans the waters between Hawaii and California, which is referred to as the Western Garbage Patch, while the Eastern Garbage Patch is located near Japan.

These spiralling patches are formed by rotating ocean currents known as gyres, which are akin to giant whirlpools, pulling marine debris in. Marine debris are then circulating into the centre of a gyre to create the garbage patches that are spread across the surface of the ocean waters.

Marine Debris and Marine Plastic Waste

In a 2018 study, the Pacific Garbage Patch is estimated to be made of at least 79 thousand tonnes of ocean plastic floating inside an area of 1.6 million km2. Over three-quarters of its mass consists of marine debris larger than 5cm, with commercial fishing nets account for at least 46%.

Though not all marine debris is visible to the naked eye and can be seen on the surface of the water; many make their way down to the ocean floor. Microplastics, which are tiny fragments of plastics broken from poorly disposed plastic waste, account for 8% of the patches’ total mass. 94% of the ocean’s microplastics (estimated to be 1.1–3.6 trillion) are found to be floating in the Great Garbage Patch area.

As ocean plastic pollution is already on track to triple by 2040, research has shown that the Great Garbage Patch is rapidly accumulating even more plastic. Without any large-scale action to reduce ocean plastic pollution, the world could discard up to 29 million metric tons per year within that timeline.

The COVID-19 pandemic has also exacerbated global plastic pollution. An estimated 1.56 billion facemasks entered the world’s ocean in 2020. Taking into account the exponential use of plastic food takeout boxes and personal protective equipment (PPE) during the period, the combined amount of plastic pollution in the sea would even be significantly higher.

You might also like: Six Wild Ways We’re Cleaning Up Ocean Plastic

The Environmental Impacts of the Great Garbage Patch

The rapid accumulation of the Pacific Garbage Patch have detrimental effects on the environment. As 46% of fishing nets account for marine debris, it poses huge risks to marine life. Marine animals easily get caught and entangled in abandoned fishing nets, causing them to choke and unable to free themselves to feed. This also includes six-pack rings and plastic bag handles.

Any marine plastic waste drawn into the pacific gyres could also accidentally transport species, such as algae, barnacles, and crabs, from one place to another. Invasive species might find it difficult to adapt to new environments and potentially disrupt the ecosystem and the local food web.

Despite how small microplastics are, they can have devastating effects on the marine ecosystem, too. Animals that mistakenly ingest marine debris or large amounts of microplastics can block their gastrointestinal tracts, or be tricked into thinking they don’t need to eat, leading to starvation. Microplastics could also stunt sea plant growth, and the reproduction rates of species like zooplankton.

What Can We Do?

Cleaning up the Great Garbage Patch should be a shared global responsibility, as it is an accumulation of waste collected from all coasts of the world. And considering the fact that plastics could take upwards of 500 years to decompose and break down, the patch would not be going anywhere anytime soon.

Though large-sized marine debris such as fishing nets can be physically removed by human efforts, The National Ocean and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) ’s Marine Debris Program has estimated that it would take 67 ships one year to clean up less than one percent of the North Pacific Ocean.

Likewise, it is near impossible to track microplastics accurately, especially in deep water layers and the seafloor. However, satellite imagery has improved over the years that have allowed for meter-sized debris items to be identified. NASA technology, primarily used for analysing wind speeds for hurricanes, can also be used to detect and track how some microplastics move, aiding efforts to clean up the sea.

Ultimately, the best way forward is to prevent plastic waste entering our oceans in the first place, and to place stricter regulations on commercial fishing, controlling the amount of fishing nets that get left behind in the ocean.

You might also like: Microplastics in Water: Threats and Solutions