The UN expects that by 2050, populations in over 55 countries (mostly developed ones) will fall. Some environmentalists suggest that population decline could be the solution to pressing global environmental problems. This article explores how population growth is linked to carbon emissions and why population decline in high-income countries might be a welcome trend but not an efficient solution to reverse global warming.

—

Projections by the United Nations (UN) indicate that dozens of countries around the world will face population decline in the near future. Europe is already experiencing this phenomenon, while Latin America and Asia are expected to follow suit in the 2050s.

Among the top-20 countries currently undergoing rapid population decline, all except two – Japan and Cuba – are located in Europe and most are high-income countries. Even China, which held the title of the world’s most populous nation until last year, when India surpassed it, experienced its first population decline in 2022. Predictions indicate that around the end of the current century, nearly all countries in the world except twelve will witness fertility rates dipping below the threshold of 2.1 needed to maintain population stability.

Governments of countries with low fertility rates are worried and see the population decline as an economic crisis. Some environmentalists, however, suggest that declining populations in high-income countries is a positive trend, since it likely leads to lower carbon emissions. Yet, when taking a closer look at the correlation between demographic shifts and carbon emissions, one can conclude that population decline in high-income countries is not a sufficient solution to stop global warming.

The Interplay Between Population Decline and Carbon Emissions

Historically, overpopulation has been linked to global warming, with the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) affirming that population growth exacerbates greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Correspondingly, other studies established a proportional relationship between population size changes and carbon dioxide (CO2).

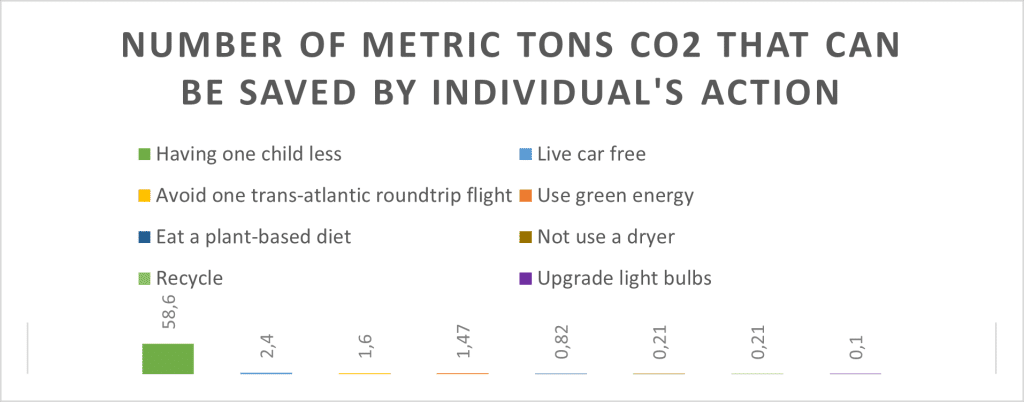

A Swedish study published in 2017 unveiled that having one fewer child per family could spare approximately 58.6 metric tons of carbon emissions annually in high-income countries. As such, not having children is in theory the most effective measure an individual in a high-income country can take to reduce their carbon footprint, more than 50 times more effective than eating a plant-based diet, recycling, or not using a dryer.

Fundamentally, a reduced global population translates to lower demand for resources such as water, wood, and energy, ultimately alleviating pressures on ecosystems. When considering this, one could argue that global population decline is a positive trend.

However, emissions are intrinsically linked to income levels, outweighing the influence of population size. Individuals in wealthy countries emit 50 times more than people living in the poorest countries, with a staggering 10% of people globally generating nearly half of global consumption-related emissions.

Hence, assessing emission contributions by country warrants a focus on emissions per capita, not solely on aggregate figures.

For instance, China, the world’s second-most populous nation, ranks as the world’s largest emitter of CO2, responsible for a third of global GHG emissions. However, its emissions per capita (8.05 tonnes) are substantially lower than those of the world’s second-largest emitter, the US (14.86 tonnes) and the fifth-largest emitter Japan (8.57 tonnes). Bulgaria and Lithuania – the two countries with the strongest population decline – emit 7.54 tonnes and 8.85 tonnes per capita, respectively. In stark contrast, Syria and South Sudan, the two countries with the highest population growth, emit merely 1.27 tonnes and 0.15 tonnes per capita, respectively.

The picture that emerges is clear: while low-income countries experience swift population growth alongside low emissions, high-income nations remain substantial emitters despite consistently declining population rates. Hence, instead of shifting blame to developing nations, high-income countries should be the ones to be held accountable for their contribution to global warming. Instead of focussing on baby-making campaigns, like Japan is doing, high-income nations need to find out how they can stop the endless cycle of consumption growth and reinvent their economies to become more circular and sustainable.

You might also like: World Population Hits 8 Billion: What Now?

Navigating Population Growth and Environmental Challenges

When it comes to the issue of global warming, the demographic trajectory of low-income countries – which are by far the most vulnerable to climate-related disasters, including floods, fires, droughts, and rising sea levels – should not be completely disregarded. Indeed, in order to avert grave global warming consequences, data shows that carbon emissions of every nation must fall below two tonnes per capita by 2050.

Sub-Saharan Africa, where half of the global population growth is concentrated, bears the brunt of climate change. The region is already grappling with frequent droughts, intense floods, extreme heatwaves, and soil erosion. Rapid population growth in those areas is believed to magnify these vulnerabilities. For instance, in Pakistan, a surge in population triggered extensive deforestation to clear land for urban expansion. Without any vegetation to bind the soil together, these densely populated areas become prone to erosion and sedimentation. These conditions increased the impacts of the 2022 devastating landslide and floods that claimed more than 1,500 lives and destroyed nearly two million homes.

All this is not to say that low-emitting developing nations with rapidly growing populations will never see their emissions rise. Historically, more wealth and elevated living standards have led to overconsumption, resource depletion, and, as a result, higher carbon emissions. To stop this trend, it is imperative to facilitate climate neutral, sustainable growth in developing countries, forestalling the mistakes that industrialised countries have made.

Research shows that sustainable population growth requires investments to ensure access to proper education, full access to contraception and reproductive healthcare, and more career opportunities for women. Estimates suggest that these measures can reduce climate vulnerabilities in poorer countries and could save 85 gigatonnes of CO2 emissions in the coming 30 years – equal to closing 22,000 coal-fired power plants. Moreover, researchers have found that lower fertility rates will not only result in lower global emissions by 2055 but they can also lead to a 10% increase in per capita income.

You might also like: Ecofeminism: Where Gender and Climate Change Intersect

Global Population Decline Is No Quick Fix

Most projections expect the global population to start declining around 2100. However, the urgency of global warming requires bold action well before then. Carbon emissions need to be cut in half this decade to prevent serious and possibly irreversible consequences of global warming. Even in scenarios where a series of catastrophic mortality events occured or forceful one-child policies were universally imposed (like China had until 2015), the world’s population would not decline sufficiently to stop global warming. This sobering projection underscores the futility of implementing population decline measures, besides the obvious ethical concerns.

The projected population decline of around 10% in high-income countries between now and 2050 could result in a quarter of the emissions reductions needed by 2050, a substantial contribution that should not be completely discarded by governments in high-income countries grappling to meet their climate objectives. However, recognising that a maximum of a quarter of emission reductions can be attributed to population decline, it becomes evident that other avenues must be pursued in the following decades to effectively and timely curtail global warming.

Is Population Decline the Solution We Are Looking For?

Global warming has a strong link with population growth. Every additional person increases consumption, resource depletion, further decline of our ecosystems and increased carbon emissions. Yet, that alone is not as nearly as decisive for global carbon emission levels..

Data speaks for itself. Wealthier countries emit far more per capita than poor countries, while nations with some of the highest fertility rates in the world and the most rapidly growing populations remain the least responsible for global warming. In this sense, overconsumption – rather than overpopulation – stands out as the central issue.

A change in the capitalistic view that dominates Western societies is what can truly help us significantly reduce future GHG emissions. But it is also important that low-income, low-emitting countries foster sustainable population growth through strategic investments and rights-based policies that empower their people via improved access to education, contraception, reproductive healthcare, and enhanced career prospects.

Implementing holistic population policies could ensure there are less people on this planet in 2100 than there are today: it is one of the cheapest and most effective emission reduction solutions available today. But this alone will not be sufficient to save our societies from the crisis we find ourselves in.

You might also like: How Does Overpopulation Affect Sustainability? Challenges and Solutions