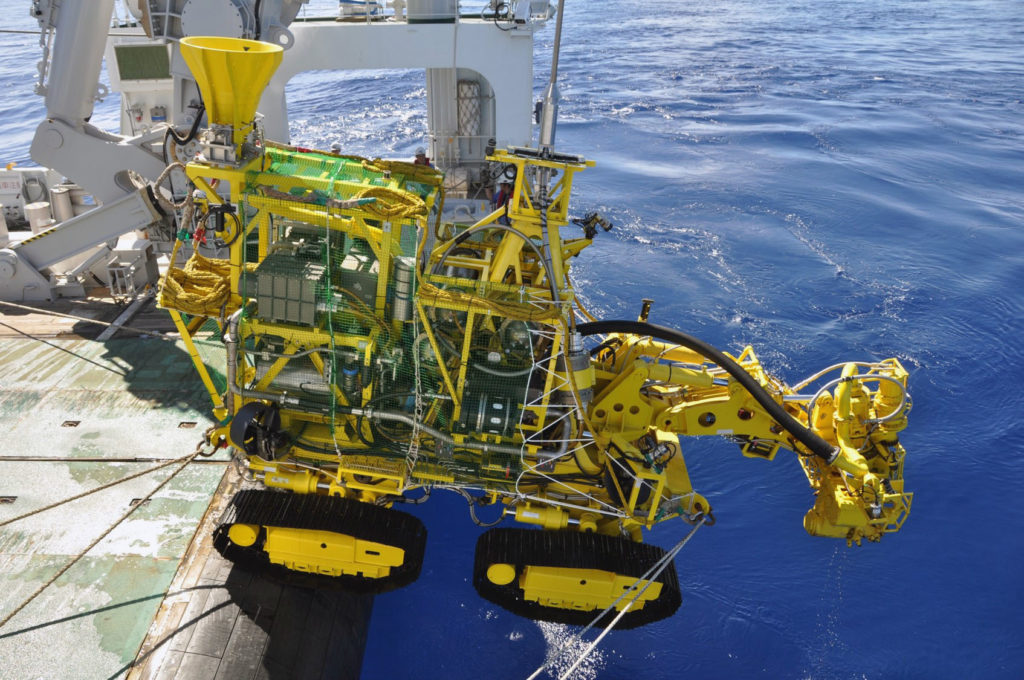

As if the existing conditions were not alarming and dire enough, our oceans are about to face yet another survival threat. The emerging deep-sea mining industry is gearing up to open a new industrial frontier in the largest ecosystem of our planet. A number of private companies plan to lower gigantic machines to bulldoze and churn up the seabed, upsetting a delicate ecosystem balance we still know little about.

—

The International Seabed Authority (ISA), a United Nations body, has issued 29 exploration licenses and distributed them to a handful of countries that sponsor private deep-sea mining companies. The licenses allow them to commercially exploit vast areas of seabed covering 1.3 million square kilometres of the Pacific, Atlantic, and Indian Oceans.

Why Deep-Sea Mining?

Abyssal plains witness a complex combination of chemical and geological processes that lead to the formation of hydrothermal vents- deposits of chemically rich fluids including sulfide pouring up from beneath the seafloor.

These vents contain minerals like copper, nickel, manganese, zinc, lithium, and cobalt, which are the main raw materials for smartphones, wind turbines, solar panels, and electric storage batteries. Global demand for these minerals has spiked while supplies from terrestrial mining remain finite and hostage to geopolitical wrangling. For instance, demand for nickel currently sits at 2 million tonnes a year, and is expected to rise to 4 million by the end of next decade.

The supply of terrestrial minerals is predicted to last for only around 40 years, prompting companies to secure the supply of these resources from the seafloor.

Countries like China, the UK, France, India, Germany, Russia, and Belgium, have now received the nod from ISA for deep-sea mining. Among these nations, China holds the largest sea mining exploration area of around 161,210 sq km, followed by the UK with an area of around 133,280 sq km.

Upsetting the delicate ecosystem on the seabed could have grave effects for us in the future. Source: Global Ocean Commission.

You might also like: Reconsidering the Role of Water in Climate Resilience

The Debate

The prospects of sea-bed mining have already been met with stark opposition from several environmental groups and scientists who predict the industry will cause colossal damage to marine ecosystems. By contrast, the ISA believes new technologies can minimise harmful impacts.

The Environmental Impacts of Deep-Sea Mining

A recent report by Greenpeace states that deep-sea mining risks potentially irreversible environmental harm, warming of ramified consequences even beyond the allotted mining zones.

Crucially, mining is going to deepen the current climate emergency by weakening the ocean’s ability to store carbon in its seafloor sediments. “Deep-sea sediments are known to be an important long-term store of ‘blue carbon’, the carbon that is naturally absorbed by marine life, a proportion of which is carried down to the seafloor as those creatures die,” the report says. “Deep-sea mining could even make climate change worse by releasing the stored carbon.”

Machines excavating the seafloor will create sediment plumes, which could smother deep-sea habitats for kilometres. Apart from the direct removal of the seafloor habitat, it will also cause a release of toxins in the processes altering the chemistry of the waters.

Potential impacts of deep-sea mining. Source: IUCN.

“The ships on the surface for the mining operation could release toxic vapours into the water, harming many ocean species for hundreds or even thousands of kilometres,” the report says. “Noise generated by churning machinery risks harming and disturbing marine mammals like whales, while floodlighting areas of the dark deep ocean could cause permanent disruption to sea creatures adapted to very low levels of natural light.”

Meanwhile, Michael Lodge, secretary general of ISA, says that the assumption of deep-sea mining inevitably causing large-scale irreversible environmental damage and ecosystem collapse seemed grossly exaggerated.

“The environmental management techniques that will be used by the Authority, contractors and sponsoring States are tried and tested,” he said. “They include environmental impact assessment, based on a collection of baseline data during exploration; long-term monitoring both during and after impact; use of best available technology to minimise impacts and risk mitigation measures.” He added that although 29 sea-exploration leases have been given out to various states, the area covered in the leases represent just a minuscule part of the entire ocean floor.

The Future of Deep-Sea Mining

The ISA is still drawing up environmental regulations on deep-sea mining, which are expected to be finished by July 2020. Industrial-scale mining cannot begin until then.

Conservationists demand the regulations should be effective enough to avoid serious and lasting harm to the environment. “We are facing a unique window of opportunity to ensure that potential impacts of these operations are properly assessed, understood and publicly discussed,” says Kristina Gjerde, Global Marine and Polar Programme senior advisor at the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). “Stringent precautionary measures to protect the marine environment should be a core part of any mining regulations.”

You might also like: The Murky Outcome of Deep-Sea Mining Negotiations in Jamaica