First deity, then monster, now shiny treasure; giant clams, the world’s largest marine bivalve molluscs, have held many amorphous names throughout the centuries. Today, their chapter as the “jade of the sea” highlights both their dual and conflicting roles: their ecological significance in supporting and monitoring coral reefs, and their high value for the food, shell, and aquarium trades.

—

Like the whale or the octopus, few creatures have been as highly mythologised in the annals of sea folklore as the giant clam. An article published in a 1924 issue of Popular Mechanics magazine, titled ‘Giant Clams Trap Sea Divers in Grip of Shells’, described the vice-like grip of clams, ensnaring unsuspecting divers unfortunate enough to step into the “open lips of the monsters” as shells closed “with such force that they serve as gigantic traps.” Coined “man-eater” and “killer clams”, this reputation is far from earned.

There are no records of battles where giant clams emerge victorious. Instead, the opposite has been proven, as giant clams share the same endangered fate as almost all ocean species. Directly, as they are handpicked and cracked open with a knife to excise their translucent white meat or dredged by large vessels for their opal shell; and indirectly, impacted by the aftermath of anthropogenic activities driving warming and acidifying waters, the true extent to which scientists have yet to fully determine.

In her book ‘The Sound of the Sea: Seashells and the Fate of Our Oceans’, environmental journalist Cynthia Barnett traces the cultural history of giant clams and their tumultuous relationship with people. The giveaway is in the name: one of two genera of giant clams, Tridacna, contains the Greek words “tri” and “dakno”, translating to “three bites.” This was, as aptly put by Barnett, “originally meant to describe not clams biting humans, but humans biting clams.”

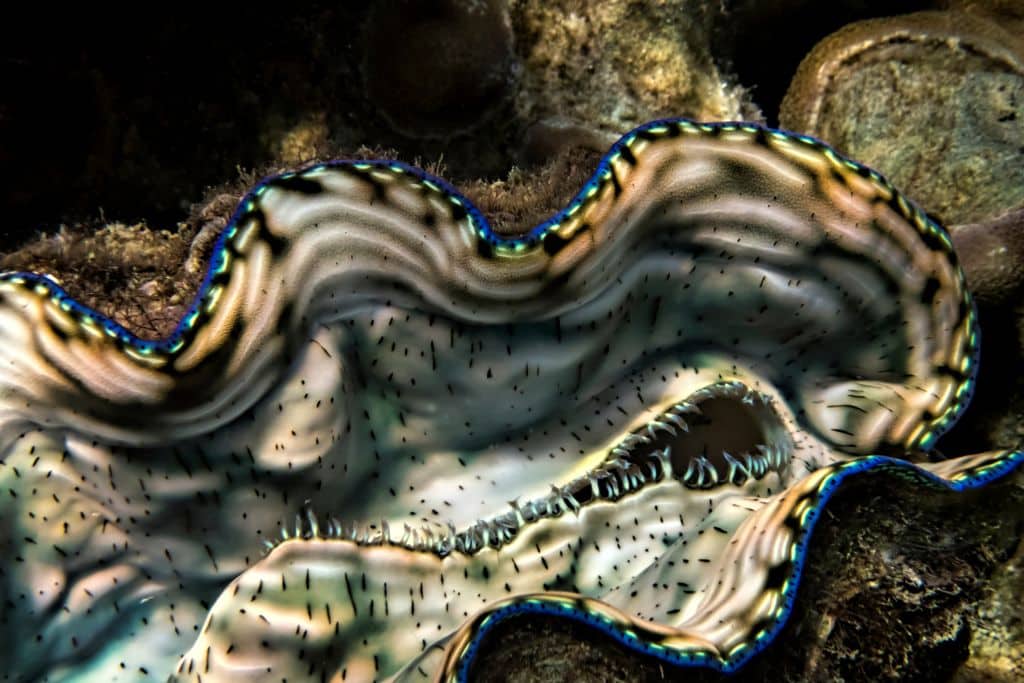

Colourful mantles contain light sensitive photoreceptors, known as iridocytes, and support symbiosis with zooxanthellae.

Shiny Lives of Giant Clams

As the world’s largest marine bivalve molluscs, giant clams comprise at least 12 extant species. The largest representative and heavyweight champion, Tridacna gigas, is a creature of superlatives, with some individuals growing to over 120cm in shell length and weighing over 250 kilograms. On a scale, these bivalve behemoths rival an African lion or American grizzly bear.

Along the shallow, sun-dappled coasts across the Indo-Pacific, giant clams lie sessile on coral reefs, seemingly so sedentary that they would impress the idlest of life forms. However, scientists have observed the giant clams’ surprising locomotive functions, from free-swimming larvae when expunged from their parent to juvenile clams using a retractable “foot” to scuttle across sandy seabeds and find suitable settlement. Distinct from their cockle cousins, who face the sky, giant clams have rotated underside; their hinge and foot lie nestled next to each other at the bottom to find anchorage. It is said that this distinctive evolution “indicates long and intimate association with coral reefs.”

Even after reaching maturity, their life cycle is far from over. Dr Neo Mei Lin, a marine biologist at the National University of Singapore, and her collaborators documented the numerous ways in which giant clams act as industrious engineers of their ecosystem, busy at work: they are providers of food and shelter, contributors to productivity, and act as reef architects and builders.

As a living kaleidoscope, the mantles of giant clams are adorned with prismatic colours that catch and shift underwater light, such as blues, purples, greens, and gold. The brightly reflective cells, called iridocytes, act as photo-receptors to detect changes in light intensity, like how the human eye may refract and process light. These colours are not mere ornamentation; rather, the vibrant mantle and tissues, like underwater citadels, harbour a bustling community of microscopic algae, known as zooxanthellae. These tiny tenants photosynthesise and provide nutrients in payment.

Sponges, corals, and invertebrates all find refuge in the nooks and crannies of the clam’s shell, creating a microcosm within the reef ecosystem. At a larger scale, giant clams provide calcium carbonate, incorporated into the foundations of the reef. As filter feeders, giant clams draw in water from their surroundings and, in doing so, accumulate any pollutants present in the water, effectively providing a living record of environmental changes over time.

This living record is what makes them invaluable biomonitors, their health and wellbeing serving as a barometer for the overall health of their surroundings. Changes in their growth rates, shell structure, or coloration can signal shifts in water quality, temperature, or the presence of pollutants, offering an early warning system of environmental stress or degradation.

“Based on the wide range of ecological functions they perform, giant clams are unique among reef organisms and therefore deserve attention,” states Neo. “Whatever safeguards can be established will not only boost giant clam populations but, by extension, also benefit coral reefs.”

How heavy must be their shells to hold up the marine ecosystems they inhabit and forecast the state of our oceans?

Giant clams are threatened by rising sea temperatures similar to corals, expelling zooxanthellae in a phenomenon known as bleaching. Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

A Less-Than-Bright Future

Before becoming a highly prized global commodity, giant clams were weaved as part of a cultural fabric as communities celebrated their connection to the sea. Giant clams have been found fossilised in ancient tools during archeological excavations, and continue to play a part in ceremonial traditions and festivals. Near stilt houses topped with sago palm thatch in Pacific Island archipelagos, families farm giant clams in a circle off a nearby lagoon as “clam gardens”. Revered spiritually, their scoping shells are used as a cache for valuables or repositories for ancestral skulls. According to Barnett, in the legends of Palau, “the clam signifies power and it signifies persistence.”

At present, nine species of giant clam are labelled “vulnerable” or “lower risk” on the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s (IUCN) Red List. All species are listed under CITES Appendix II, meaning that, while they are not necessarily threatened with extinction, international trade must be legal, sustainable, and traceable to ensure their continued survival. These three prongs are, however, neither easy to confirm nor deny. Disparities in import and export figures reported by state parties already indicate unreliable reporting. As Neo suggests, “the CITES and IUCN data for giant clams are outdated and potentially misleading.”

After more recent reviews of giant clam stocks and their distribution, scientists are now calling for an update to its conservation status with grim news: Tridacna gigas is already locally extirpated in many areas of its native range, and other species are in substantial decline.

There is growing evidence to support the overestimation of giant clam populations. Giant clams have been sold as curiosities and souvenirs and to decorate aquariums, predominantly in the US and Europe, while their abductor muscles, which hold the two halves of a bivalve together, became a valuable ingredient for gastronomic Asian cuisine, and their shells propping a burgeoning shell-carving industry in China and Japan, to be fashioned into statues and jewelry.

As documented in a 2021 report by the Wildlife Justice Commission, authorities in the Philippines have made 14 seizures of giant clams since 2016, with some stockpiles weighing in excess of 120,000 tonnes. The report indicated a correlation with China’s national ban on ivory products in 2017, raising concerns that giant clams are the “new” ivory. As an alternative to elephant tusks and rhino horns, the ban may drive consumer demand underground, although no smuggling route has been identified. Even more complicated is the terse geopolitical background in which the illegal trade finds its moorings: disputed territorial waters and rising global tensions in the Pacific Ocean, and a continued race for resources. Marketed as “jade of the sea” and “white gold”, one thing is clear: giant clams, and their iridescent colours, hold both ecological and economic value, and the balance is currently tipped.

Scientists are also sounding the alarm about climate change and its irreversible impacts on the ocean, to which giant clams are not immune. Stressed by rising temperatures, giant clams may evict their algal partners in a phenomenon known as bleaching. Without their main food source, giant clams, like coral, turn from rainbow to a sickly white, leading to stunted growth and, at worst, death. Mass mortalities of giant clams have been reported as part of major bleaching events in 1997-1998 and again in 2015-2017, linked to unusually warm sea surface temperatures triggered by the El Niño Southern Oscillation. Their physiological responses and adaptive capacity remain a mystery.

The culmination of these threats, scientists fear, is a loss of biodiversity. It is not only a count of the number of different species, but the variety of genes within those species and the role they play within their ecosystem. In a study assessing functional traits and extinction risks of marine megafauna, giant clams are considered one of the top five species both functionally vital and most vulnerable, threatening its legacy as a symbol of power and persistence.

Giant clams are the world’s largest marine bivalves, with the largest species reaching over 120cm in shell length and weighing over 250 kilograms.

Clamming for Conservation

Coastal communities have long observed and monitored giant clams, adopting customary law and engaging in husbandry techniques for sustainable harvest. The importance of giant clams is nothing new; to them, giant clams have always been the focal point of coral reefs and the main indicator of reef health. Now, together with those communities, conservationists strive to restock coral reefs and advance the science of mariculture – the cultivation of marine organisms in their natural habitats – converging with traditional farming practices and clam gardens. By breeding and raising giant clams in controlled environments, conservationists hope that mariculture may offer an alternative to wild harvesting, replenishing depleted populations while also providing livelihood opportunities.

The current approach to giant clam conservation appears significant, yet insufficient. Perhaps at this juncture, it is time again for giant clams to morph into something new: to shed its shell as jade and gold-glinted treasure and be recognised, as it always was, as an integral piece of the marine environment. This means not only understanding giant clams and their symbiotic algae partners or how they respond to different stressors but also addressing the interconnected nature of these challenges and committing to protecting the ocean as a whole, before giant clams do, in fact, become a myth.

You might also like: 11 of the Most Endangered Species in the Ocean in 2023