The recent analysis found that species in the UK – already classified as one of the world’s most nature-depleted countries – have declined by 19% since monitoring began more than five decades ago.

—

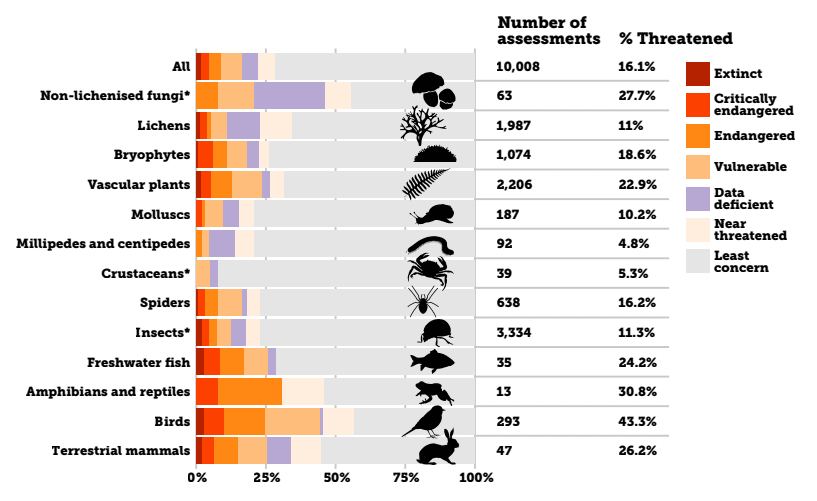

One in six species is at risk of being lost in the UK, a world-leading study on biodiversity in the country has found.

Over 60 researchers and conservation organisations assessed ten thousand species in what is considered the most comprehensive analysis of the UK’s biodiversity. They found that wildlife in the country has declined on average by 19% since widespread monitoring began in 1970, though evidence suggests that biodiversity had already been “highly depleted” by reckless human activity, including traditional farming practices and rapid urban development on land as well as unsustainable fishing, marine development, and climate change at sea.

A 2022 report had already suggested that climate change-triggered extreme weather events in the UK are devastating for wildlife. The study found that last year’s extreme temperatures and low rainfall – which resulted in the UK’s warmest year on record – posed significant challenges for the country’s animal and plant species.

According to this year’s State of Nature report, which uses the latest data from biological monitoring and recording schemes to provide a benchmark for the status of wildlife in Great Britain, 54% of flowering species – including Heather and Harebell – and 59% of bryophytes – such as mosses, liverworts, and hornworts – are at risk of extinction.

Plant species like heather flowers, iconic features of the British and Irish landscape, are under threat. Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

As for animal species, the report suggests that birds are those facing the biggest threat, with approximately 43% of all bird species at risk of disappearing in the coming decades. According to the report, over 70 bird and mammal species have been affected by the recent Avian influenza outbreak, the worst the UK has ever experienced, which led to the culling of more than 4 million domesticated birds and the death of an estimated 50,000 wild birds. Seabirds, notorious international travellers, are believed to have come in contact with the virus in the UK, the outbreak’s epicentre, subsequently spreading it across the globe.

More on this topic: Unprecedented Avian Flu Outbreak Continues to Decimate Bird Populations

Endangered bird species are followed by amphibians and reptiles, fungi and lichen, and terrestrial mammals, with 31%, 28% and 26% at risk of disappearing, respectively. Pollinators, upon which more than 80% of the world’s plant crops depend for survival, have also been disappearing at an average of 18% since 1970.

Summary of IUCN Red List assessment for Great Britain. Image: State of Nature 2023.

“The UK’s wildlife is better studied than in any other country in the world and what the data tell us should make us sit up and listen. What is clear, is that progress to protect our species and habitats has not been sufficient and yet we know we urgently need to restore nature to tackle the climate crisis and build resilience,” said Beccy Speight, Chief Executive of the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds.

The report also assessed habitats crucial for wildlife’s survival and found that only one in seven is in good condition. As for woodlands and peatlands, only about 7% and 25% respectively were found to be in a satisfactory ecological condition.

You might also like: What Is Brighton’s Bee Bricks Initiative?

Conservation Efforts Are Showing Promising Results

The report identifies a few conservation bright spots, such as a 2008 dredging and trawling ban in the Lyme Bay Marine Protected Area, which has contributed to an increase in various marine species populations, as well as large-scale restoration projects such as Cairngorms Connect, which is benefitting many woodland-dependent species across a vast area within the Cairngorms National Park in northeast Scotland.

According to Richard Gregory, Head of Monitoring and Indicators at RSPB, stepping up conservation efforts in the 11% of the country that is already legally protected would make “a huge difference.”

“We have swaths of land, such as national parks and areas of outstanding natural beauty, that are not really being protected because the management is not up to scratch,” he told the Financial Times.

“We know that conservation works and how to restore ecosystems and save species. We need to move far faster as a society towards nature-friendly land and sea use, otherwise the UK’s nature and wider environment will continue to decline and degrade, with huge implications for our own way of life. It’s only through working together that we can help nature recover,” said Speight.

You might also like: 7 of the Most Endangered Species in the UK in 2023