As the decade’s most pivotal climate talks are underway this week in Glasgow, Scotland at the 26th UN Climate Change Conference (COP26), climate financing will inevitably be one of the main talking points. The industrialised world has pledged to submit financial assistance to developing nations in order to accelerate the global transition towards decarbonisation and net-zero, but progress has so far been minimal. As climate justice and equality become bigger and bigger ideas, it is worth asking how we got here. What does the developed world owe, and how do we make sure that the world’s wealthy few fulfil their climate debt?

—

At the UN’s 2009 climate summit in Copenhagen, the industrialised world reached an agreement to provide international financial support, or climate finance, to help poorer countries adapt to climate change. The pledge ensured that the most vulnerable nations to climate change would have access to adequate resources in the short and long term to minimise global temperature rise’s disastrous effects on the developing world.

Wealthy nations eventually pledged to direct USD$100 billion a year towards adaptation and resilience in the developing world, starting from 2020. But as of 2021, the industrialised world has failed spectacularly at delivering on its pledge.

Official numbers indicate that the fund totalled between $70 and 80 billion a year by 2018, but further investigations have revealed that the vast majority of this was in the form of loans that would have to be paid back by developing nations, which more or less defeats the purpose of the whole initiative. When considering only grants and low-interest lending, the real number was between $19 and 22 billion.

Wealthy nations have issued a revised statement pledging that the funding will arrive no later than 2023, in full. But as climate finance takes the stage at COP, it is worth diving deeper into the dark history of climate debt. How much does the industrialised world really owe everyone else?

What Is Climate Debt?

In September 2017 Hurricane Maria made landfall on the US territory of Puerto Rico, causing USD$43 billion in damages and nearly 3,000 deaths. The devastating event was supercharged by climate change, which makes storms of this magnitude nearly five times as likely to occur. CO2 emissions in Puerto Rico are around 0.22 tonnes per capita each year. In the continental US, emissions per capita are 15.52 tonnes, over 70 times higher.

The Marshall Islands, a low-lying island nation in the South Pacific, is responsible for 0.00001% of global emissions, and is yet facing a very real threat of becoming partially uninhabitable as early as 2035 due to sea-level rise. The South Asian country of Bangladesh contributes to less than 0.1% of climate-altering emissions, but is still one of the most vulnerable countries in the world to climate change due to its low-lying topography, economic reliance on agriculture and high poverty rates.

This is the bedrock upon which the concept of climate debt is founded. Developed countries owe a debt to the developing world because they are the ones responsible for the vast majority of global emissions and ecological devastation. At the same time, the countries who will bear the worst impacts of climate change are those least responsible for them.

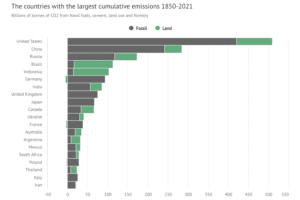

Climate debt takes into account how historically prominent greenhouse gas emitters, like the US and EU, have vastly exceeded their fair share of emissions, while other countries who took longer to industrialise have barely scratched the surface in comparison. It is why countries like China and India, today the first and third largest emitters in the world respectively, have pleaded with the US and other historical polluters at COP26 to provide more climate financing.

Source: Carbon Brief; 2021.

How do we ensure that the world’s most climate vulnerable, the people on the frontlines of the climate crisis, do not have to face catastrophe alone and unprepared? The answer is climate finance, aid directed towards the most vulnerable and provided by the industrialised world. Climate finance is intended to put the world’s most vulnerable countries in a better position to adapt, mitigate and build resilience to the threats posed by climate change.

Climate debt spotlights the interests and needs of peoples and nations historically underrepresented in the climate financing debate, filling in the gaps where net-zero pledges and emissions reduction targets cannot accurately represent the cost being shouldered by developing countries. While climate debt needs to be repaid to help the world cope with a warmer future, it still remains unclear how much countries are willing to pay off.

Who Pays, and How Much?

However industrialised countries choose to repay their debt to the world, questions will inevitably rise over who has to pay, and how much. The aforementioned $100 billion by 2020 pledge failed in part because wealthy nations never really sat down to talk about how much each of them should be expected to contribute, and how to measure each of their commitments.

This has repercussions on a global scale, because without this financing, developing nations are being forced to bear irrationally high adaptation costs on their own. According to the African Development Bank, Africa holds 15% of the world’s population, is responsible for around 3% of global energy-related CO2 emissions, and yet is currently forced to “shoulder nearly 50% of the estimated global climate change adaptation costs.”

The divergence in responsibilities is stark. In a 2020 study, researchers quantified the fair share emissions of every country in the world if we were to stay within a ‘safe’ planetary boundary roughly equivalent to 1°C of warming (a threshold we have already passed). The study found that the world’s most industrialised countries were responsible for over 90% of excess emissions today. Virtually every developing country was within the boundary for its fair share of emissions, and perhaps most tellingly, so were China and India. Despite these two countries’ high contributions to current emissions, their fair share pales when compared to the historical emissions of the US and EU.

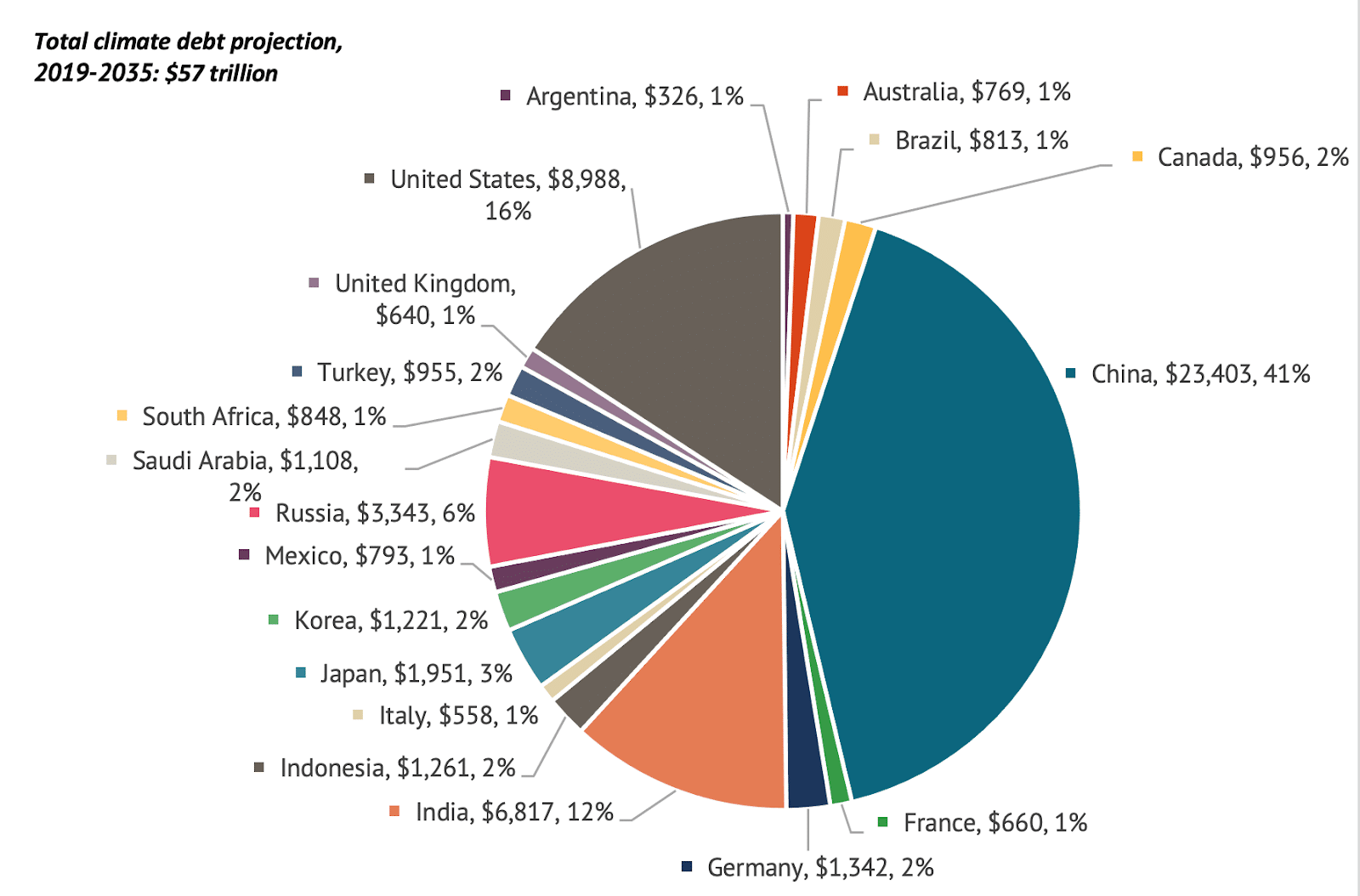

The total value of climate debt, how much industrialised countries owe to the developing world, may currently be as high as $34 trillion. Based on current estimates of how much carbon will cost us in the future (the social cost of carbon, currently pegged at $51 per tonne of carbon emitted), this number may swell to be as high as $57 trillion by 2035, mainly due to China’s rise and continued usage of fossil fuels.

That is if the social cost of carbon is fixed at around $50, but if we want to stay in sight of the global target to keep average temperature rise below 1.5°C, the reflective social cost of carbon would have to be at least $100, if not much higher. According to agro-ecologist Max Ajl in his 2021 book, A People’s Green New Deal, the world’s climate debt would be $112 and 448 trillion by mid-century if we want to stay below 1.5°C of warming. For reference, current global GDP is around $80 trillion.

Despite their frankly unreasonable size, these sums are not impossible to pay off, especially if the industrialised world starts doing so early while also making every effort to keep emissions down within their own borders. But climate debt is not only about money. It is also about history and legacies of extractivist and exploitative relationships between the developed world and its neighbours. The consequences of these relationships, in many cases going back to the European colonial era, are clearer now than ever, and leaders will need to reconcile these less tangible debts as well.

You might also like: Is Carbon Trading a Solution for the Climate Crisis?

Paying Off Our Debts

At COP26, leaders from the developing world have been doing everything in their power to make the reality of their homelands’ dire circumstances clear. “They [big emitters like the US and China] are not only destroying lives, they’re destroying livelihoods,” Gaston Browne, Prime Minister of Antigua and Barbuda told Axios. “And if this situation continues, the alternative situation is literally losing our lives, losing our civilisation in the Caribbean, Pacific and Indian oceans.”

To fairly compensate these nations, and to reach a more equitable future, monetary transfers won’t be enough. Countries will need global transformations in the ways they use energy, how they employ transport and how they interact with neighbours. This means providing patent-free clean energy tech transfers to the developing world at a near-zero cost. It means treating emissions as financial debt, valorising domestic biodiversity and investing in technologies to sequester more carbon. It means making borders more open, easing visa procedures and providing the right for climate migrants to live and work wherever they are forced to go.

Climate debt is seeped in a long and often bloody history of inequality and unequal relationships, making it very difficult to quantify. And much like the legacy of climate debt reaches far into the past, it will extend similarly far into the future. As strategies move on to how we can adapt to a warmer climate rather than avoiding it altogether, developing nations will be faced with an exponentially escalating number of crises. To fully pay off its debt, the industrialised world will have to be ready to handle the consequences.

Discussions on climate finance at COP are necessary, but they have to be followed by tangible policies that ensure these payments materialise. In the second week of the conference, talks over a global carbon market plan are expected to progress, plans that were initially proposed in Paris six years ago but have yet to find any real traction. There is growing optimism that these plans may actually turn into policy soon, which would be a definite game-changer in our efforts to pay off climate debt and build global resilience. Reaching an agreement and setting well-designed rules for an international carbon market could well be what make or break this year’s climate talks.

An international carbon market would take us a step closer to treating emissions as financial debt, an undesirable asset that becomes more and more invaluable the longer it stays in the atmosphere. If designed correctly, a global carbon market could unleash trillions of dollars’ worth of investments into green energy, clean technology and adaptation measures. Given recent commitments by the private sector to mobilise financial support towards climate resilience in the developing world, at least some of these returns can be reinvested into adaptation and paying off the climate debt.

There remain some problems. A badly organised deal for a global carbon market with lax rules might be worse than no deal at all, as it might simply allow wealthier corporations and countries to emit more while shifting the blame elsewhere. And as ever, it wouldn’t be a proposed climate solution without a classic COP-related problem rearing its ugly head: credibility, or rather the lack thereof. Members in any eventual international market would need to ensure that their actions are credible, and the best way to do that would be to actually show that their emissions are falling and the revenue from the carbon market is going into expanding green technology.

If well-designed rules for an international carbon market are established this week, developing nations will have a reprieve in the form of trillions of dollars’ worth in adaptation measures, and investments will pour into clean technologies, making future energy transfers easier to envision. And the more countries are brought onboard to a global market, the faster this transition will happen and the cheaper it will be in the long run.

Climate debt, at least in theory, is not a radical proposal. It simply asks the ones who made the mess to take responsibility and clean it up. Its implications, however, are enormous. Repaying our debt in full would entail an enormous transfer of wealth, which is why wealthy nations have been opposed to it or have played ignorant about it, despite the lack of any real logical argument against climate debt. It makes perfect sense that wealthy countries would have to repay it, but under current circumstances, that probably won’t be enough to make them do so.

An international carbon market could go a long way towards paying off our climate debt by changing the norms that make debt so unattractive to talk about right now. Getting countries on board, and vilifying those who refuse to, is the first step towards ensuring the climate debt crisis is met in a reasonable time frame, but it is only the start. Climate debt can be an important tool in our arsenal, because it highlights something that is often forgotten: the inequality of climate change. This will be a long process, but making sure that our leaders are talking about the problem in honest terms will be the first step.

Featured image by: UN Women Asia Pacific/Flickr