In recent weeks, the European agricultural landscape has witnessed a wave of protests and demonstrations by farmers, who have raised concerns about their livelihoods and the future of farming in the region. The protests, which have garnered significant attention, were sparked by a series of contentious agricultural policies proposed by the European Union (EU). However, last week’s U-turn by Brussels on some key agricultural policies has added a new dimension to the ongoing demonstrations, leaving many questioning the implications for farmers and the future of European agriculture.

—

What Is Going On?

In recent weeks, farmers across several European countries have taken to the streets, clogging hundreds of roads and using their tractors to occupy squares and shut down borders.

Last month, an estimated 30,000 farmers as well as representatives from fishing, gastronomy, and other industries blocked the main road leading to the Brandenburg Gate in Germany’s capital Berlin, bringing the city centre to a standstill. Just a few hundred kilometres to the West, infuriated French farmers blocked access to the capital Paris, while others dumping manure and rotting produce in front of government buildings.

Last week, around 1,000 tractors descended on the heart of the European Union in Brussels, Belgium, ahead of a key meeting to secure more funding for war-torn Ukraine. Some were hurling eggs and sparking fires, while others held signs with slogans such as “No farmers, no food.” Several border crossings were also targeted by protests, with tractors blocking the Belgian-Dutch border and occupying roads connecting Spain to Portugal. In Poland, farmers have repeatedly threatened to shut down the border with Ukraine.

This week, Italian farmers from different regions have been heading south en masse towards the capital Rome, chanting slogans, carrying hand-written signs, and displaying the Italian flag.

What Are Farmers Protesting Against?

There is no straightforward answer to this question since a lot of the frustration is somewhat specific to the agricultural and political traditions of each country, with farmers protesting poor wages, high taxes, and rising costs.

It is true to say, however, that European farmers share a common sentiment amidst a tense geopolitical context that has resulted in higher prices and taxes and increased competition with foreign countries.

Among the major stumbling blocks are trade relations between the bloc and Ukraine, a European country but not yet part of the European Union. In 2022, the EU granted Ukraine full trade liberalisation, temporarily lifting import duties, quotas, and trade defence measures on Ukrainian exports to support the country’s economy following Russia’s invasion. The move has been heavily opposed by farmers in neighbouring Bulgaria, Hungary, Poland, Romania, and Slovakia, which describe competition from Ukraine as “unfair.”

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine also led to a bloc-wide energy crisis which raised costs of production and essential services such as heating, electricity, logistics, and transportation, creating market uncertainty and straining the financial stability of farmers. The tumultuous state of the energy market also played a significant role in driving up EU-wide inflation, as reflected in a substantial increase in the consumer price index for electricity, gas, and fuels. Notably, within a span of two years, energy prices in the agricultural sector have surged by a staggering 86%. Input prices and trade flows were also affected. The price of cereals, for example, is currently about 30% lower than pre-invasion, from €80.6 billion (US$87.1 billion) in 2022 to €58.8 billion (US$63.5 billion) in 2023.

Farmers are also facing unprecedented challenges as a result of climate change. In particular, back-to-back extreme weather events including droughts, wildfires, and floods have impacted output and revenue in various European countries. In 2022, nearly half of Europe experienced the worst drought the region has seen in at least 500 years, which scientists said was made “20 times more likely” by climate change. By September, about 17% of Europe was estimated to be experiencing impacts on vegetation and crops as a result.

According to European Commission data for that year, crops including grain maize, soybean, and sunflower experienced elevated yield losses, though rice was by far the most affected, with EU-wide yields 20.9% below the 5-year average as most rice-growing regions, including Italy, Spain, France, Portugal, Romania, and Hungary experienced long-lasting rainfall deficit and hot temperatures.

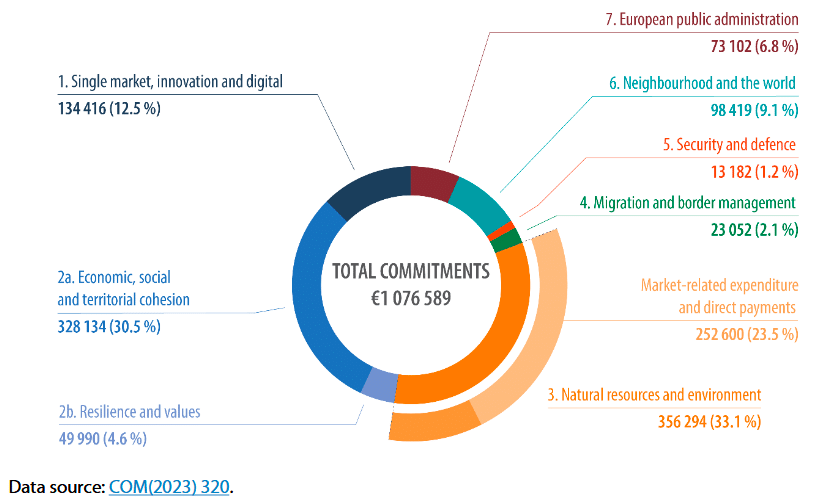

But at the centre of the protests is also a list of sustainability policies aimed at revamping the €55 billion (US$59.4) Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), the EU’s oldest and costliest policy that implements a system of agricultural subsidies and other programmes. Farmers argue that the new green rules will decrease competitiveness with countries that have less stringent environmental regulations.

The EU allocates around a third of its budget to environmental policies and the agricultural sector, despite it representing around 1.4% of European gross domestic product (GDP) and employing around 5% of workers.

While it is true that the agricultural sector plays a strategic role in the food security of the entire continent, its environmental impact cannot be understated. Agriculture is the fourth-largest in terms of greenhouse gas emissions in the EU, and it is among the sectors that have seen the least progress in terms of mitigating its environmental impacts since 1990.

To keep on track with its emissions reduction targets – a 55% reduction by 2030 and carbon neutrality by mid-century – the bloc has introduced revisions to the CAP, which was launched in 1962. Among the nine new rules the EU is set to introduce are requirements for farmers to implement crop rotations, cut fertiliser use by at least 20%, and leave at least 4% of arable land fallow or unused, all prerequisites for farmers to access funding.

However, farmers have repeatedly pointed out at the unequal distribution of EU funding and subsidies, which are largely allocated based on agricultural area and thus end up benefitting large corporations rather than small farmers. It is estimated that approximately 54.2% of all subsidies for the agricultural sector in 2022 were assigned to the top 10% of Europe’s largest corporates, while the smallest farms, which make up 50% of all European farms, received a combined 6.3% of the subsidies.

The European Union Is Backtracking

In a major win for European farmers, the European Commission announced last week it would delay green rules that would have required them to set aside land to promote biodiversity and healthy soil.

In a press release, the Commission announced all EU farmers would be exempted from the requirement for one year, adding that farmers growing certain environmentally friendly crops on at least 7% of their arable land will be regarded as fulfilling the requirement. These include crops that contribute to nitrogen fixation – such as lentils, peas, and favas – as well as catch crops – quick-growing crops planted between the main crops that maximise land use while preventing soil erosion.

“Today’s measure offers additional flexibility to farmers at a time when they are dealing with multiple challenges,” said Ursula von der Leyen, president of the European Commission. “We will continue to engage with our farmers to ensure the CAP strikes the right balance between responding to their needs while continuing to deliver public goods for our citizens.”

European Commission vice-president Maroš Šefčovič described Wednesday’s decision as “a helping hand” for the hard-hit sector and said the Commission demonstrated “flexibility and solidarity” with European farmers.

“By enabling the production of nitrogen fixing crops and catch crops, without the use of plant protection products, this derogation strikes a balance between the short-term necessity of supporting farmers and the long-term need to protect our climate, soil health, and biodiversity,” he said.

In a statement, the European farming lobby Copa and Cogeca criticised the move, saying it “comes late in the agricultural calendar and remains limited” and calling on EU leaders to do more.

“We hope that member states will further strengthen this proposal to have a more global approach especially in member states that have been particularly impacted by extreme climate events, during the European Council meeting tomorrow,” the statement read.

Ariel Brunner, head of EU Policy at the environmental NGO BirdLife International, said on X (formerly Twitter) that the proposed exemptions would “[destroy] flowerstrips and fallows” and “further [lock] farmers into dependency” on the chemical industry.

Last week, Brussels also tabled a proposal to limit the import of sensitive agricultural products from Ukraine, including poultry, eggs, and sugar, and re-introduce tariffs if imports exceed average levels for 2022 and 2023. On Tuesday, it announced it will also scrap a plan to halve pesticide, marking a further concession to protesting farmers and yet another blow to the bloc’s environmental agenda.

“This is a first good sign that the Commission will work with farmers to tackle climate change rather than against them,” said Alexander Bernhuber, the European People’s Party (EPP) Group’s chief negotiator on pesticides. “We have always said that it would be irresponsible to jeopardise European food production in the face of current crises through unrealistic requirements and bureaucracy. We are ready at any time to work together with the Commission for effective climate protection and a secure food supply.”

What Now?

The EU finds itself in a precarious position regarding agricultural reforms, as several factors contribute to a continuous cycle of deferring crucial decisions. The upcoming EU elections in June are expected to usher in a more populist parliament that leans towards pro-farmer policies.

One key aspect exacerbating the issue is the EU’s decision to limit agricultural references in its 2040 emissions targets. By doing so, agricultural reforms are effectively postponed beyond 2040. While this may provide some temporary respite, it also sets the stage for a more arduous journey towards achieving sustainable agricultural practices in the future. The EU is banking on the hope that the political landscape will be more favorable by then.

As a consequence, the burden of reducing emissions is shifted onto other sectors such as energy, transport, and manufacturing, which are already grappling with their own challenges, making it a daunting task to take on additional responsibilities.

Furthermore, the EU’s support for its farmers has drawn criticism from the international community. Critics argue that the EU’s substantial investment, with agriculture accounting for a third of its budget, creates an uneven playing field for non-EU farmers who struggle to compete with the world’s largest bloc. This disparity in support further fuels the perception that the EU is evading tough burdens by shifting them onto farmers outside its jurisdiction.

As the EU grapples with the complexities of agricultural reforms, the need for a comprehensive and sustainable solution becomes increasingly urgent. The delay in decision-making, coupled with the burden placed on other sectors and the international criticism, highlights the challenges the bloc faces in striking the right balance between supporting its farmers and addressing broader environmental concerns.

Ultimately, Europe’s ability to navigate this delicate situation and find a path forward that ensures both agricultural sustainability and fairness among global farmers will shape the future of its agricultural policies and its standing in the international community.

Featured image: Liepāja fotogrāfijās/Flickr

You might also like: European Commission Recommends Ambitious 90% Greenhouse Gas Emissions Reduction Target by 2040

This story is funded by readers like you

Our non-profit newsroom provides climate coverage free of charge and advertising. Your one-off or monthly donations play a crucial role in supporting our operations, expanding our reach, and maintaining our editorial independence.

About EO | Mission Statement | Impact & Reach | Write for us