A week ago, a tragic flood filled a South Korean underpass with deadly waves, leaving at least 46 dead. However, this is not the first time relentless flooding wreaked havoc on South Korea’s streets. After one too many heavy rainfalls, the nation admired for its elaborate soft power is now facing heavy scrutiny as the public begins to question its climate crisis resolutions. In this article, we explore how climate change is unfolding in South Korea.

—

The Cheongju Tunnel Incident

On the morning of July 15, 2023, a ferocious wave of flood waters rushed into a 430-metre (1,410ft) underpass in western Cheongju, located southeast of Seoul. The tunnel’s motorists could not outrun the speed of the flood, leaving many unable to escape.

Ultimately, the death toll climbed to 46, with 4 missing people. 15 were vehicles trapped in the underpass, including one bus and 12 cars. About 16,000 residents have since been evacuated to shelters, 30,000 hectares (74,121 acres) of farmland have been damaged, and 693,000 livestock have died.

With South Korea entering the climax of its summer monsoon season, the Cheongju flood was triggered by a series of torrential downpours that drenched the country for weeks. The heavy rainfall caused a massive overflow in a nearby dam that also blocked the tunnel’s entryway.

Back in May, the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) predicted that a strong El Niño, the first one since 2020, would occur during the summer, pushing temperatures “off the charts”. El Niño is a climate pattern that results from the unusual increase in water temperatures. Meanwhile, The Korean Herald reported that July was predicted to have a 40% chance of precipitation higher than or similar to the yearly average.

On the Monday after the incident, South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol conducted a meeting on Disaster Response. While the President primarily blamed the authorities’ failure to follow rules to tackle the disaster, he declared that “extreme weather events” are the new normal.

“We need to tear down perceptions that these situations cannot be helped because they’re unusual,” Yoon said. “We need to deal with them with extraordinary determination.”

South Korea’s Floods and Typhoons

The horror of the Cheongju flood reignited similar sentiment from last year’s fatal flood in Seoul, where the city experienced the heaviest rain in 115 years since records began in 1907. The record-breaking downpours killed nine people and left 17 injured.

On August 8, 2022, Seoul was rocked with the heaviest daily rainfall of 381.5 millimetres, dethroning the previous record of 332.8 millilitres in 1998. The rainfall also brought a series of fierce lightning that struck the city more than 2,000 times in one night. The destructive rain flooded multiple low-lying residencies, particularly killing residents of banjiha, otherwise known as basement apartments.

Another historic flooding occurred back in the summer of 2020, when heavy rainfall flooded the city of Daejoon. It was the longest monsoon in seven years, with 42 consecutive days of rain. The disastrous rain killed 15 people and forced 1,500 people out of their homes.

In the same year, three consecutive tropical cyclones hit the country within two weeks in August and September, causing a whopping 676 power outages nationwide. Consequently, 290,000 households had no electricity, six nuclear power reactors stopped working, and renewable sources failed to provide the electricity needed due to a lack of solar irradiation and aggressive winds exceeding the speed limits.

Causes of Erratic Weather Conditions

In South Korea, the summer season naturally occurs during July and August, when both temperatures and precipitation reach their peak levels.

According to an analysis by Korea Meteorological Administration, the annual weather averages between 1990 and 2018 show that July and August have the highest temperatures of 26.8C and 29.9C respectively. Meanwhile, July has the highest precipitation level of 285.5 millimetres, followed closely by August with 274 millimetres.

South Korea’s annual weather report by Korea Meteorological Administration. Image: Fourth National Communication of the Republic of Korea.

As shown in the table above, July and August are the most vulnerable months when it comes to heatwaves, rainfalls, and tropical cyclones. These natural phenomena have significantly intensified in recent years due to climate change.

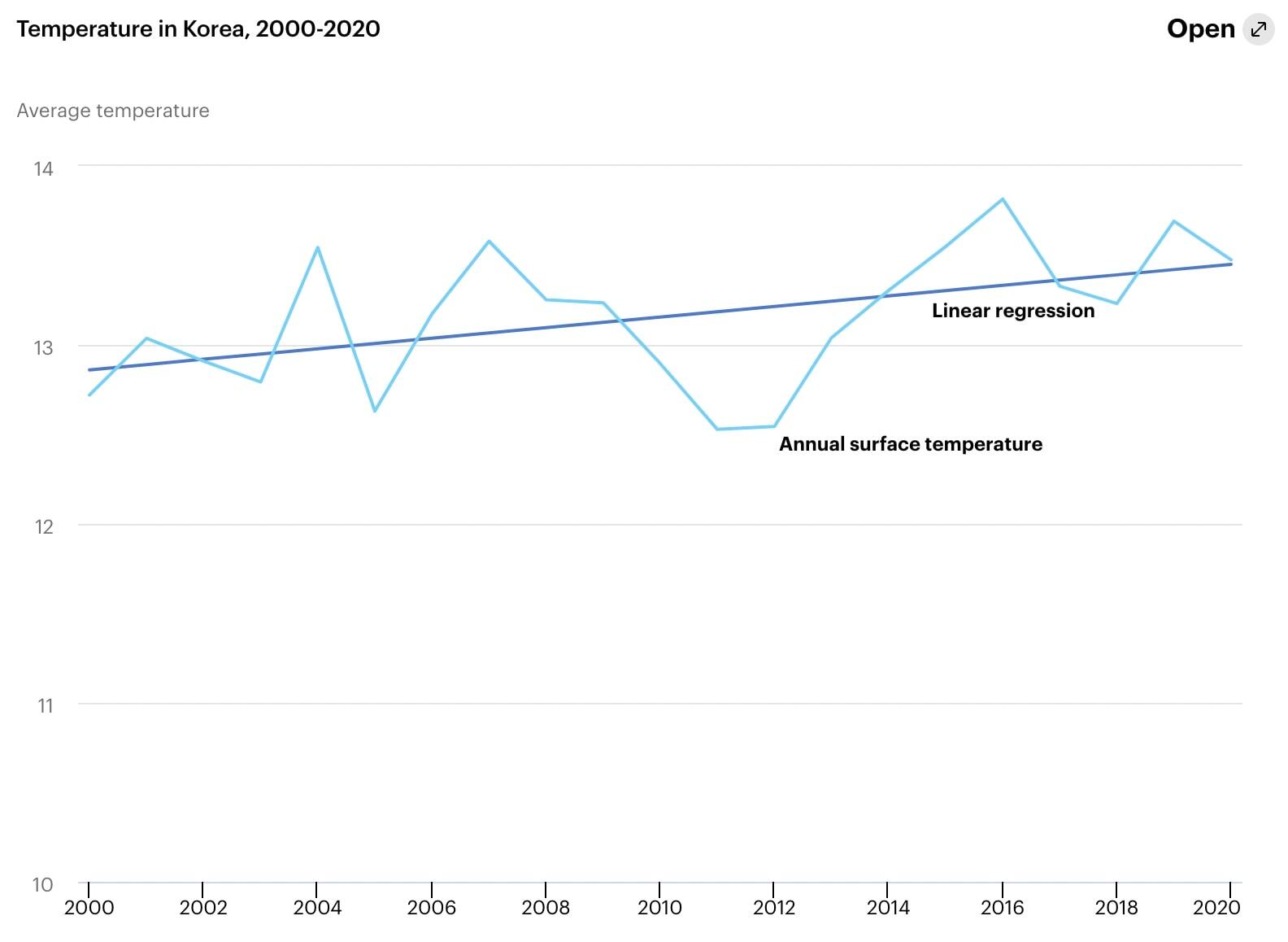

The country has been no exception to the global warming crisis, with temperatures rising by 0.23C (32.41F) per decade between 1954-1999 and by 0.5C between 2001 and 2010, according to a 2021 report by the International Energy Agency (IEA). Between 2000 and 2020, South Korea has seen a 0.6C (33.08F) increase in annual temperatures.

The annual surface temperature of South Korea has a continuous increase. Image: IEA/Korea Climate Resilience Policy Indicator.

While it may seem unrelated at first glance, the increase in temperatures largely contributes to the exceptionally destructive typhoons in the nation. Tropical cyclones are boosted by warmer seas, and a warmer atmosphere holds more moisture, so the storms bring more moisture ashore which leads to more intense rainfall. South Korea has grown notorious for its extensive events with tropical storms, as it experienced nine tropical cyclones from 2000 to 2020, more than eight times the global average.

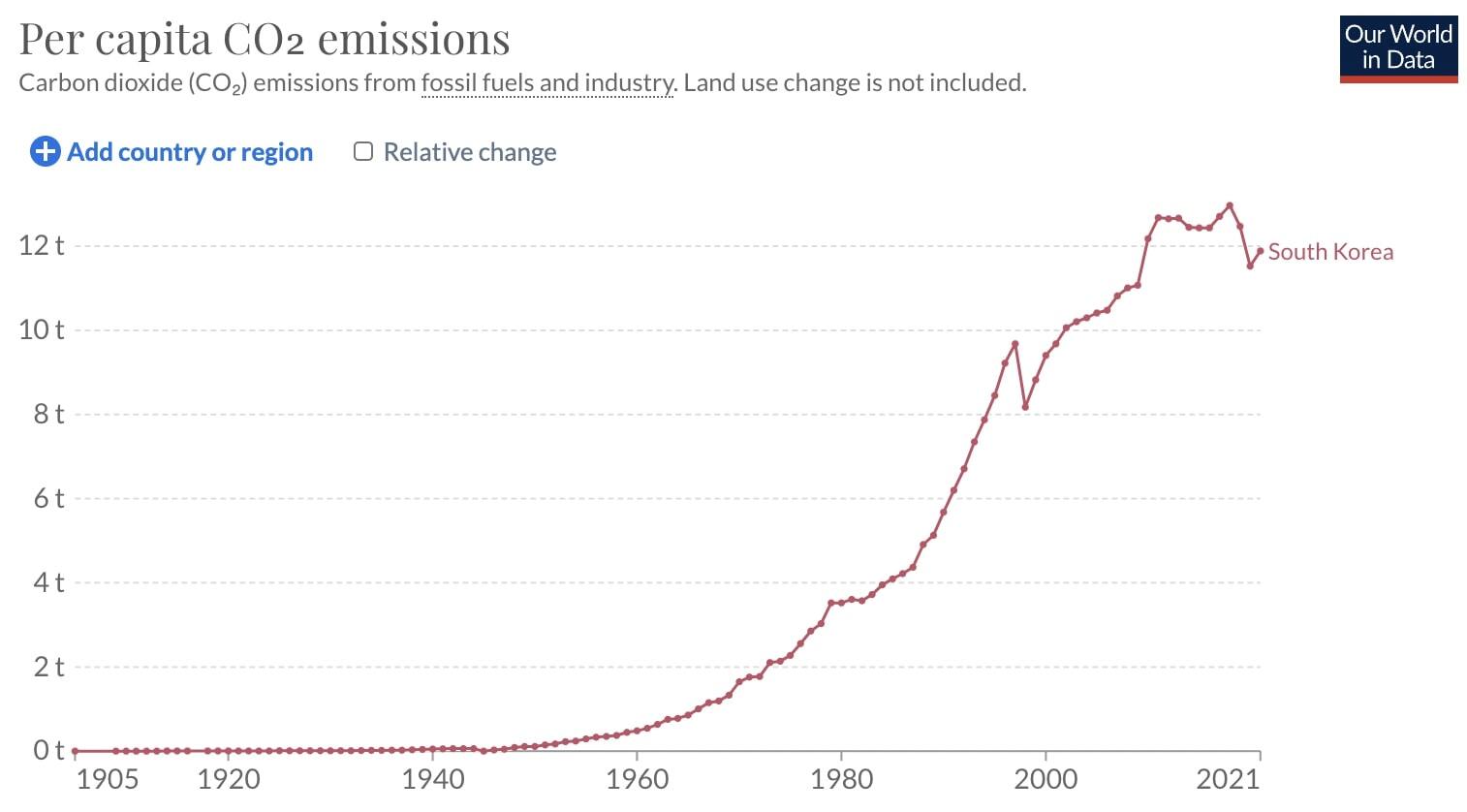

However, the situation simply boils down to our contributions to climate change, and South Korea is far from being innocent when it comes to greenhouse gas emissions. In the most updated report, Our World In Data shows that South Korea had 11.89 tonnes of carbon dioxide emissions per capita in 2021, making it one of the top emitting countries in the world.

South Korea’s carbon dioxide emissions per capita has increased dramatically in recent decades. Image: Our World In Data.

From unnecessary food packaging to the prevalence of single-use plastics, South Korea’s plastic consumption is another crucial factor in its unfolding climate crisis. In the most recent Statista report, around 91% of coastal waste found in South Korea in 2022 was plastic. This implies that plastic waste is largely disposed of in seawaters, where they emit methane and ethylene due to sunlight exposure, as proven by a 2018 research article. Subsequently, these emitted greenhouse gases only worsen the climate crisis in South Korea.

Government Response

In contrast to his words about the Cheongju Tunnel incident, President Yoon Suk Yeol has done little to combat climate change and has instead added fuel to the fire.

Earlier this year, Yoon declared that Seoul might have to invest in nuclear weapons in response to North Korea’s nuclear threats. This nuclear rhetoric is supported by his stance against renewable energy. During the presidential election last year, Yoon dismissed the notion of committing to RE100, an initiative to wholly transition to renewable energy by 2050.

“That 100% renewable energy doesn’t make any sense,” Yoon said during the TV debate.

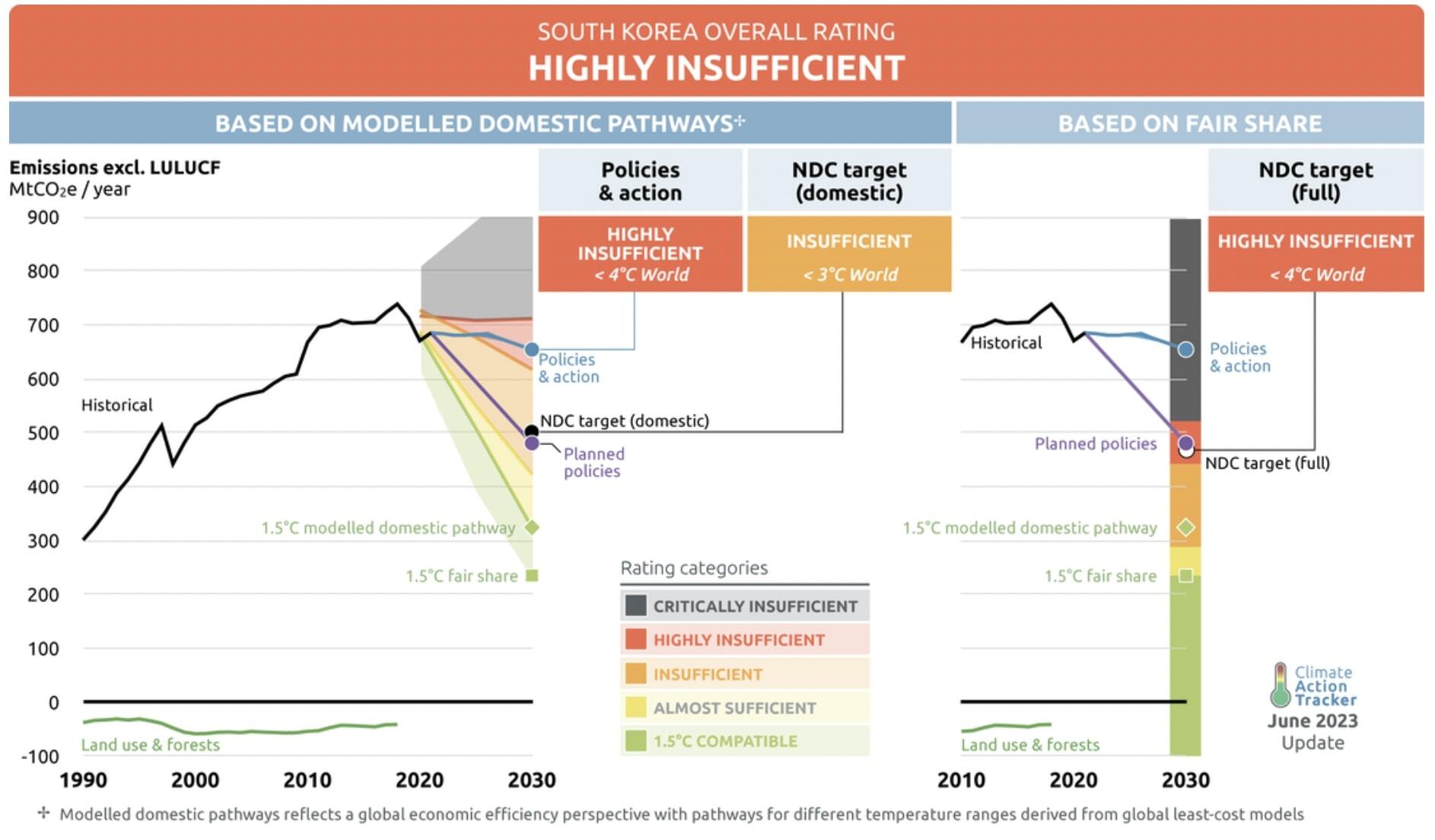

According to Climate Action Tracker, South Korea’s overall rating for its action against climate change is classified as “Highly Insufficient”, indicating that the country’s policies do not align with the Paris Agreement. This conclusion is derived from the assessment of government policies throughout the years.

South Korea’s overall climate action is classified as “Highly Insufficient.” Image: Climate Action Tracker.

In January 2023, the government enacted the Tenth Electricity Plan, which aims to utilise nuclear energy in a bid to decarbonise the country. Contrary to the initial goal of capping the nuclear share at 30% by 2030, the Tenth Electricity Plan raises the proportion of nuclear energy usage to 34.6%. This increase in electricity generated implies the development of six new nuclear reactors alongside the existing 12 reactors. This policy goes directly against former President Moon Jae In’s goal of gradually abandoning nuclear power.

Although nuclear power does not emit greenhouse gases, it should not be considered the ultimate solution to climate change as it provides additional risks that prove to be far more life-threatening. For example, nuclear-related accidents, high costs, complex construction, incompatibility with wind and solar power, and sensitivity to heatwaves.

In January 2012, the Renewable Portfolio Standard (RPS) was enacted in the country. According to the IEA, the programme aims to expand renewable energy usage and make it a promising market competitor. Through this, the biggest 13 power companies were required to increase their renewable energy usage to 10% in 2012-2024. The aforementioned plan, however, stifles the RPS by lowering its ratio from 14.5% to 13% in 2023.

In the Fourth National Communication of the Republic of Korea, published in 2009, the nation declared a target of reducing 30% of greenhouse gas emissions by 2020. It is not clear whether this goal has been achieved. Nonetheless, the recent backtracking policies already prove that South Korea’s drive for climate action has been dwindling.

While South Korea has been garnering international attention for its influential music and TV shows, it has undoubtedly been lagging behind in terms of climate action. Without proper implementation of its policies, they will merely be words on paper. Until we stray away from carbon emissions and nuclear power, torrential rains and tropical cyclones will continue to rock the streets of South Korea, and the rest of the world.

You might also like: 15 Biggest Environmental Problems of 2023