As the world wrestles with the post-pandemic future, it is clear that the world order cannot follow a business-as-usual approach. As the world’s sixth mass extinction event draws nearer, more economies are beginning to embrace a ‘closed’ or a ‘circular economy’ model: notably, the EU released its Circular Economy Plan that aims to end the ‘throwaway culture’ plaguing society. To make this a reality, the very ideas of growth and consumption need to be challenged.

—

The Nobel prize-winning economist Milton Friedman famously said, “The only corporate social responsibility a company has is to maximise its profits.” When such an approach drives much of the capitalist world’s business, the natural outcome is a greed-driven, consumerist society that is categorised by the depletion of natural resources, pollution and environmental degradation that has led to humanity experiencing climate tipping points that may irreversibly damage the path of civilisation as we know it.

What is a linear economy?

This economic model has been based on the so-called linear economy philosophy of ‘Take, Make, Use, and Dispose’. In such a model, the true cost of goods and services is hidden due to a lack of accounting for the cost of pollution caused to the air, water, land and sea, as well as the remaining value of the product when it is discarded. It is estimated that the cost of such so-called ‘externalities’ is a significant burden even in purely economic terms. None of the world’s leading corporations would be profitable if they were to account for the natural capital that they use.

The idea of a circular economy (CE) dates back to the 1960s when economist Kenneth Boulding discussed the adoption of a closed economy (imagining the earth to be a space ship) as opposed to the open economy we have now (also called a ‘cow-boy economy’). The ‘throwaway’ nature of the closed economy model was replaced by the ‘Make, Use and Reuse’ model, or the ‘circular economy’ model for the first time in a 1976 report by Walter Stahel and Genevieve Reday for the European Commission.

Circular Economy: Examples

The best way to understand what a circular economy is is to examine a real-life case study. Take lighting. A lightbulb could be designed to last a lifetime but it would be unprofitable for manufacturers to do that, called ‘planned obsolescence’. Appliance company, Philips, has created a new service called “Circular Lighting,” whereby users pay only for the light, not for the equipment. Phillips will pay for the installation, performance and servicing of the lighting. At the end of the service contract, the lighting system can be upgraded and reused, or all materials and parts can be returned for repurposing or recycling, minimising materials and waste and forcing the manufacturer to take responsibility for the entire life cycle of the product.

Apple is another example of a company embracing circular economy principles. The company announced in 2017 that it would be making new iPhones, iMacs, and other products from 100% recycled materials. The company currently has a scheme where customers can bring in their old products to get a discount on an upgrade- it estimates that up to a third of those coming into an Apple Store to purchase a new phone are trading in an old one.

Around 44.7 million tons of e-waste was generated globally in 2016, of which 435 000 tons were mobile phones.

The EU is enshrining the principles of a closed economy into its laws; in early March, the EU released its Circular Economy Action Plan which requires manufacturers to make products that last longer and are easier to repair, use and recycle. Taking effect in 2021, the plan is a part of the EU’s targets to become a climate-neutral economy by 2050 as outlined in its New Green Deal.

Currently, we are dependent on linear industrial processes where we use finite natural resources to create products with a limited service life that end up in landfills or incinerators. A circular economy is inspired by living systems like organisms that process nutrients that can eventually be fed back into the production cycle. Biomimicry, ‘cradle to cradle’ instead of ‘cradle to grave’, closed-loop, or regenerative are some of the other terms usually associated with it.

In 2018, the World Economic Forum (WEF), World Resources Institute (WRI), Philips, the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and other partners launched the Platform for Accelerating the Circular Economy (PACE) to scale up circular economy innovations. PACE has three focus areas: blended finance (especially for developing countries), policy frameworks, and public-private partnerships. Global corporations like IKEA, Coca-Cola and Alphabet Inc., along with the governments of Denmark, The Netherlands, Finland, Rwanda, UAE, and China, among others, are members of PACE. China’s 11th Five-Year Plan included the promotion of a circular economy as a national policy beginning in 2006.

The British Standards Institution (BSI) developed and published the first standard for a CE in 2016. A report by McKinsey titled “Towards the Circular Economy: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition” has identified significant benefits of implementing a circular economy model across the EU, including net materials cost savings worth up to US$630 billion annually in the manufacturing sector alone.

A circular economy can also contribute to meeting the emission reduction goals of the Paris Agreement. An analysis by Ecofys and Circle Economy estimates that circular economy strategies can reduce the gap between current commitments and business as usual by about half.

The Doughnut Model

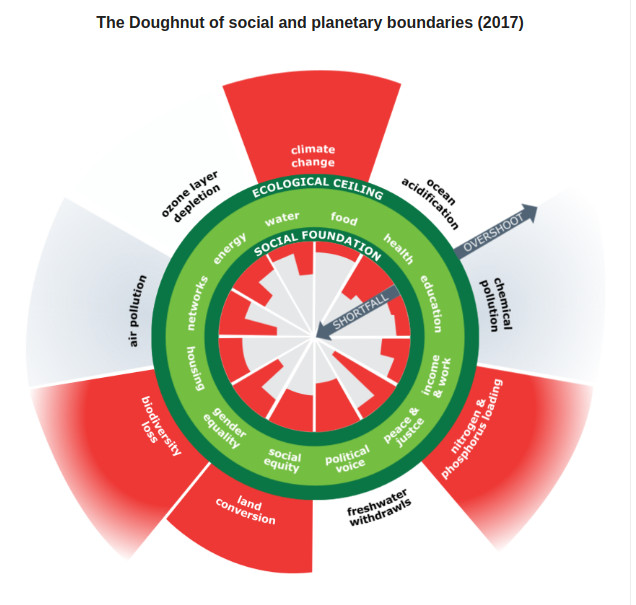

While a circular economy model can serve as a great model for a progressive economic and business framework, the world needs a broader approach that integrates complex socio-political ideologies that often drives the preference of economical models. In recent times, it has become increasingly clear that a free market-driven open-ended growth model is unsustainable and is the primary driver of global heating leading to the ecological breakdown and climate crisis. In 2012, Kate Raworth, a senior research associate at Oxford University introduced the idea of a Doughnut Economy that aims to make human welfare the basis of economic policy rather than the all-pervading pursuit of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth.

Economic welfare was defined as per the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) that provide a set of minimum living standards by the UN for every human being. She extended the basic circular flow of money and goods model of economics by adding the nine planetary boundaries (environmental limits imposed by the planet) on the outside and social boundary consisting of SDGs on the inside – forming a doughnut. In this model, economic progress is measured in terms of the balance between human wellbeing and protection of the life support systems provided by the planet, thus mitigating global warming, ecological break-down and climate change. Since its introduction, this post-growth economic thinking has attracted the attention of a range of actors ranging from the UN General Assembly to Occupy the London movement. As many countries start re-examining prevalent strategies and economic policies in light of the current COVID-19 pandemic, the foundations of the Doughnut Model are being explored for the long-term planning and policy development of cities like Amsterdam.

Sharon Ede, co-founder of the Post-Growth Institute, writes, “A truly circular economy would mean that the circular ethos is also reflected in our social systems, including our financial services, our business structures, and the political frameworks and cultural norms that influence human behavior.” Humanity needs to move away from consuming in excess and shift to consuming only that which is necessary to exist.