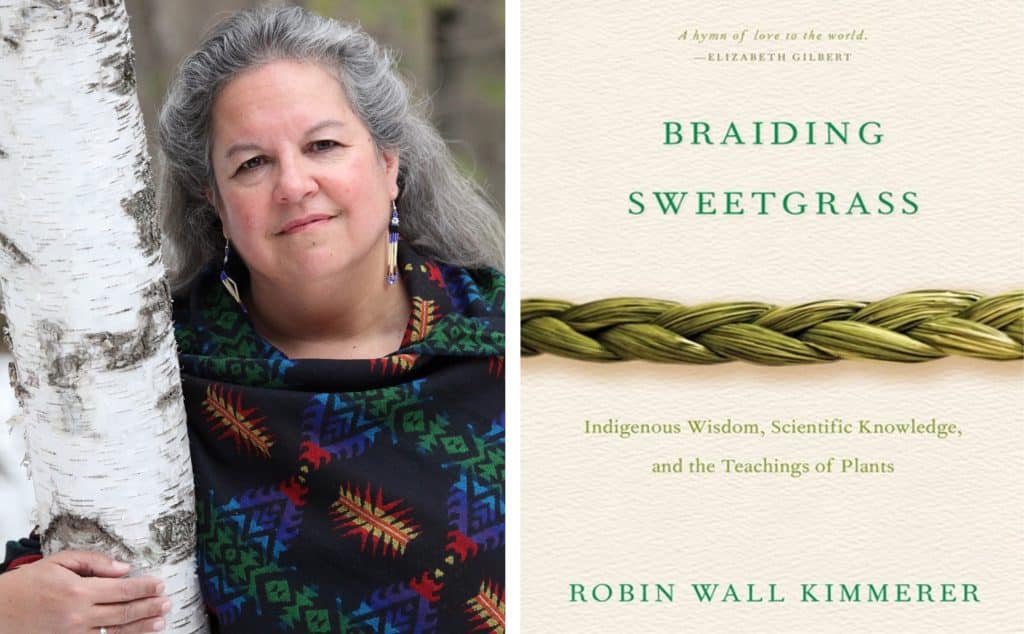

Can you list an example of one interaction between society and the environment that benefits them both? This is the question that Robin Wall Kimmerer, a mother, scientist, decorated professor, and member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, asked her students at the beginning of Botany 101. In many ways, Braiding Sweetgrass is a response to this question. The book is an epic project that puts indigenous and scientific ways of knowing in conversation with each other. It is at once a memoir, a historical cultural narrative, and a hopeful manual in the face of the climate and biodiversity crises. Throughout the book, Kimmerer intertwines her experiences as an indigenous woman, her ongoing project to reclaim lost indigenous ways of knowing, and her long career as a practicing bryologist (a botanist specilising in the study of moss and bryophytes), culminating in a celebration of humanity’s historical reciprocal relationships with the rest of the living world. Braiding Sweetgrass encourages this awakening within a wider ecological consciousness.

—

Braiding Sweetgrass is first and foremost a project of revival. It is a project that works to decolonise the roots of modern science. For example, when European settlers first colonised North America, they embarked on a systemic erasure of indigenous ways of study and learning. Western science in many cases supplanted indigenous ways of knowing up to the modern day within mainstream understandings of land, ecosystems, and resource preservation. At the same time, the nature of the scientific method means that things like ethics and morality are excluded by necessity from scientific lines of questioning, even while many issues underlying climate change, the biodiversity crisis, and global social and material inequality stem from the intersection of nature and culture. Therefore, we cannot rely on ‘unbiased’ scientific ways of knowing alone in order to address these issues.

In Braiding Sweetgrass, Kimmerer explains the difference between science, indigenous wisdom, and learning as the difference between looking and listening. Where on the one hand, science encourages us to observe, be specific and unbiased, on the other hand, indigenous teachings encourage us to listen, recognise, and be led by what we study.

Braiding Sweetgrass introduces us to this way of knowing by framing understandings of nature in terms of gifts. Potawatomi teachings, for example, instruct learners that each being (plants, animals, rocks, rivers, lakes, etc.) has a gift to give, and that it is our job to listen to that being, and learn what its gift is. For beings like edible plants, their gift is food. Edible plants are amazing gift givers, and turn inanimate material into energy that is shared with other beings.

The first chapter in Braiding Sweetgrass is Kimmerer’s retelling of the creation story of the Haudenosaunee people, and other iterations of this story are told by indigenous people across the Great Lakes region of what is now called North America. It is the story of skywoman, a pregnant woman living in skyworld that suddenly fell through a hole in the floor. The hole allowed light to reach the world below. As skywoman fell, the animals living in the world below saw her and rescued her. A flock of geese flew up and cushioned her fall. The world she landed on was made completely of water, and so she took refuge on the back of a turtle’s shell. The animals wanted skywoman to have dry land to live on, and so they took turns diving to the bottom of the water to fetch mud. None of them could, until the muskrat eventually reached the bottom of the water, grabbed a fistful of mud, and drowned while swimming back to the surface. When the muskrat’s body reached the surface, skywoman took the mud from its paw, and danced in gratitude for the muskrat’s gift. As she danced, she kicked the mud around until it spread out and became land.

This is the Haudenosaunee creation story about Turtle Island, nowadays known as North America. After skywoman created this land, she planted seeds throughout it, so that when she gave birth to her child, they could thrive in this new world created in a partnership between skywoman and the animals.

The story of skywoman is full of reciprocal gift-giving.

For example, the animals gave skywoman the gift of mud (and therefore land) and in return, skywoman cultivated the land with every known plant species. This creation story is an amazing way to frame how Braiding Sweetgrass wants us to understand our place on the world. That the world is full of gifts for us, but equally importantly, that we are full of gifts for the world. Many non-indigenous people struggle to imagine ways to live in harmony with the environments that they inhabit, but indigenous people everywhere have endless examples of this kind of living. Braiding Sweetgrass invites us to inhabit such examples from Kimmerer’s life and studies.

The author invites us into what she calls “the web of reciprocity” wherein ecosystems are vast networks of gift giving – from producer to herbivore, herbivore to carnivore, plant to human, and human to plant. Gifts, and gift-giving, are core to to the idea that Braiding Sweetgrass presents in terms of how we currently frame concepts like sustainability in the climate movement. To Kimmerer, sustainability implies preserving systems that allow for us to extract resources in perpetuity, whereas reciprocity implies that the Earth is a being that cares for humanity, and humanity has the capacity and responsibility to care for the Earth in return.

A core example of the human capacity to give gifts to the world in Braiding Sweetgrass has to do with a concept called “the honorable harvest,” which is a way of procuring food that in turn bolsters an ecosystem’s resilience. The Anishanabee people, for example, depend on manoomin (or wild north american rice) for sustenance. Manoomin grows along wetlands, and so in the late summer, when the wetlands flood, Anishanabee people go out in boats to harvest it. Their harvesting technique results in about 40% of the manoomin harvested being ‘lost’ or dropped back into wetland habitats.

However, this practice is not done on accident: as the Anishinabee harvest manoomin, they also actively seed the wetlands for the next year’s harvest. The honorable harvest in this case is a means of reciprocal gift giving to the manoomin plant. It exists in many forms throughout the world, but underscores a culture of care within indigenous communities. Where every plant has a purpose, or ‘gift’ to give, ensuring and harbouring biodiversity is equally important and beneficial to more-than-human and human communities, stewardship is humankind’s gift in return. Braiding Sweetgrass presents this way of knowing ecosystems as an integral part of “the gift economy,” where gifts become more valuable the more they are given.

In another chapter, Kimmerer narrates a scientific study on the merits of the honorable harvest, which found that the honorable cultivation of plants does indeed benefit the plant in the long run, either by freeing up space for the plant’s offspring, or by distributing seeds to appropriate niches. This is just one instance where Kimmerer is able to merge indigenous and scientific ways of knowing, creating a multifocal lattice for us to use in the face of the unfolding climate and biodiversity crises.

Braiding Sweetgrass as a whole is a rare book that feels hopeful, relevant, and full of love. In her same botany 101 lecture, Robin Wall Kimmerer asked her students if they loved the Earth, after they responded with a resounding “yes”, Kimmerer then asked her students if they thought the Earth loved them back. Her students did not know how to respond to this question because, if the Earth loved them back, it would presuppose an idea that the Earth as a being had come to know everyone personally. This question lies at the core of Braiding Sweetgrass, it is a book-length lesson that ultimately reassures its readers that the Earth does, in fact, love them back.

Robin Wall Kimmerer

2015, Milkweed Editions, 408pp

You might also like Earth.Org’s review of How to Prepare for Climate Change: A Practical Guide to Surviving the Chaos