The growing popularity of Mount Everest has resulted in various forms of pollution spoiling the fragile ecosystem of the region. This article delves into the root causes of pollution on Mount Everest and addresses the need for responsible tourism and sustainable practices to mitigate the issue.

—

Background

Mount Everest, located in the Mahalangur Himal sub-range of the Himalayas in Nepal, is the world’s highest mountain, reaching an elevation of 8,850 metres above sea level. Since the first climbers summit Everest in 1953, New Zealand mountaineer Edmund Hillary and Tibetan guide Tenzing Norgay, climbing the mountain has become a popular expedition for hiking enthusiasts around the world.

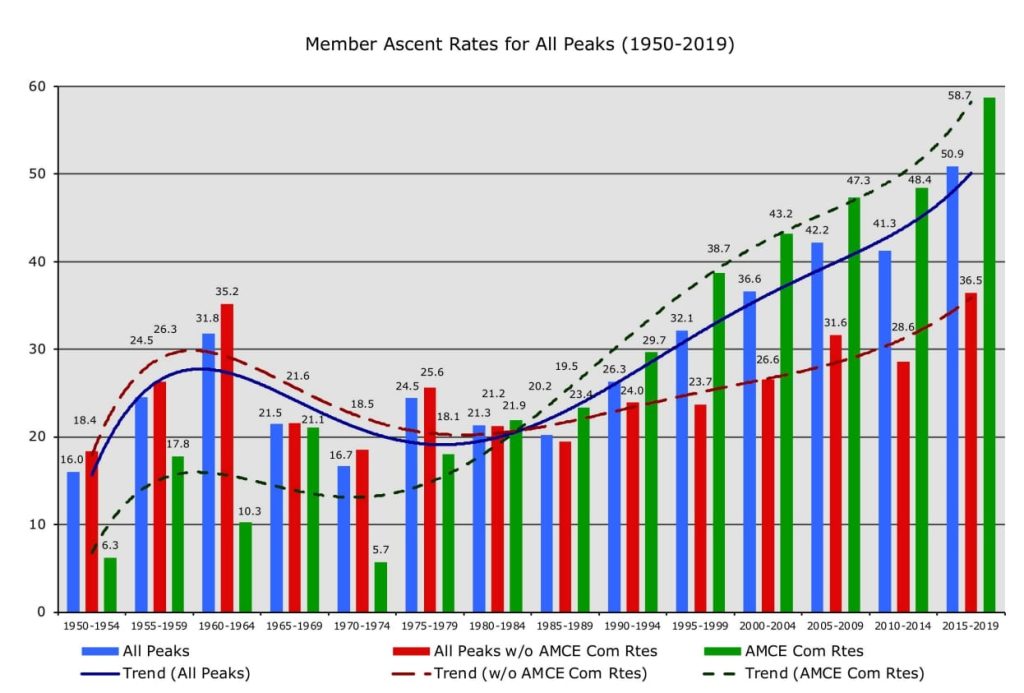

There has been a significant surge in the number of tourists and mountaineers visiting the Sagarmatha National Park, which is home to Mount Everest. According to official data published in 2021, mountain expeditions experienced an upward trend, from 3,600 in 1979 to more than 58,000 tourists in 2019.

Traditionally, conquering Everest’s summit required mountaineering skills and physical endurance levels that require years of practice and experience. After all, climbing Everest is a potentially deadly activity, with life-threatening risks such as hypothermia, frostbite, avalanches, and deadly altitude sickness.

Today, the situation is different. Unlike in the past, with the commercialization of mountaineering, climbers who pay expedition fees that can range anywhere between US$32,000 and $200,000 can attempt to reach the summit. 2023 saw a record high climbers, with authorities issuing a total of 463 permits.

Increasing Pollution

The exponential rise in tourism has led to significant issues in the region, particularly related to pollution.

1) Dead Bodies

Between 1990 and 2019, more than 300 people have lost their lives in an attempt to set foot on Everest. On average, six people die every year while ascending and descending the peak. 2023 had the record high death toll, with at least 12 climbers dead and an additional five either missing or assumed dead.

Oftentimes, bodies are never found or retrieved due to the mountain’s extreme climate and the logistical challenges it poses. Carrying these bodies back to the base camp is not only challenging but also potentially fatal for rescue teams.

For this reason, many bodies are left behind. According to a 2015 investigation by the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC), Everest’s slopes are currently home to more than 200 corpses.

2) Human Excrement

A lack of solid waste management system means that streams of human excrement are circulated by the glaciers up in the mountain on a regular basis. Although local climbers are employed to haul the human waste down from Everest base camps in barrels to dispose into landfills near the village of Gorak Shep, the waste often gets washed downstream, especially during the summer monsoon season.

Mountain geologist Alton Byers estimated that approximately 5,400 kilograms of human waste is collected from the base camps each year. While this number accounts for the collected dumping, one can step out of the base camp tents, and still stand on minefields of human excrement.

Every year, human excrement has been a rapidly worsening problem in the Sagarmatha National Park through a combination of inaction and ineffective measures. Some climbers defecate in biodegradable bags, which, however, are said to be expensive, while others dig holes, which eventually emerge back to the surface as temperatures in the region keep rising, melting the ice cover. The South Col Glacier, which sits between Mount Everest and Lhotse at around 7,906m (25,938 ft) above sea-level, has lost more than 180ft (54m) of thickness in the last 25 years.

As human excrement leak to the Base Camp or Sherpa communities, they contaminate the landscape and can spread of airborne, which can result in lower-intestinal and upper-respiratory infections as well as waterborne diseases such as cholera and hepatitis A among climbers and local communities.

3) Solid Waste

High altitude expeditions require investment of pricey life supporting equipment, including tents, ropes, portable gas stoves, ladders, tins, and cans. All this contributes to waste issues, with Earth’s highest point estimated to be covered in around 30 tonnes of garbage.

An assessment on stream water and snow samples from Mount Everest conducted between April and May 2019 found that microplastics are omnipresent in all collected snow samples, with the highest concentration of microplastics found at Everest Base Camp. Microplastics found in 53 out of 56 snow samples were linked to fibres from outdoor clothing. Particularly polyester was the most prevalent polymer detected in both snow and stream samples (56%), followed by acrylic (31%), nylon (9%), and polypropylene (5%). The study concluded that microplastics are likely from clothing and equipment used by the climbers and trekkers.

More on the topic: Microplastics Found Near Summit of Mount Everest

Are Authorities Doing Enough?

To combat solid waste generated by climbers, the government of Nepal in 2014 implemented a deposit scheme requiring all summiteers to deposit US $4,000 prior to the expedition. In order to get the money back, they are required to return to the Base Camp with at least 8 kilograms of waste each, the average amount estimated to be produced by an individual during the expedition.

The Nepali government also frequently mobilises its army to go on cleanup expeditions to Mount Everest. For example, in 2019, along with non-governmental organisations, the Nepali army collected over 2 tonnes of waste, and in 2023, the army-led Mountain Clean-up Campaign collected 35 tonnes of waste on four mountains including Mt. Everest, Mt. Lhotse, Mt. Annapurna, and Mt. Baruntse.

Several non-governmental organisations and private companies are also leading and organising campaigns to clean-up and to educate climbers and local communities on the importance of solid waste management.

One such exemplary organisation is the Sagarmatha Pollution Control Committee (SPCC), established in 1991 to promote environmental sustainability through the development of sustainable waste management infrastructure and educate the local community on the 3Rs: reducing, reusing, and recycling. Another organisation aiming to tackle the human waste crisis in the region is the Mount Everest Biogas Project, which is building a solar-powered biogas system powered by human waste to supply local communities with sustainable fuel.

Suggestions

Though governmental, non-governmental and private organisations have worked collaboratively to manage the waste pollution, it is important to note that so have the number of climbers over the decades. Waste management and waste reduction practices alone are not enough, especially in pristine places like Everest, because they fail to address the crux of the problem.

The regulatory measures for Everest expeditions in Nepal pale in comparison to what other countries are doing in terms of strengthening control over expedition formation, flow of expedition traffic, security arrangements, and environmental protection.

A great example of this is China. Here, expedition organisers who meet standards set by China Tibet Mountaineering Association will get preference over others. What’s more, mountaineering teams qualified to climb the Everest from Nepal route are not allowed to climb from Tibet. In regards to traffic control, China only issues 300 climbing permits to foreigners annually. Security-related provisions in the country include one guide for each summit climber, and foreign tourists are not allowed to go on solo climbs, a rule that Nepal introduced just last year.

The Nepali government should prioritise accountability and supervision on perpetrators by implementing measures similar to those in place in China. Moreover, sustainable approaches in terms of sustainable climbing clothes and equipment should be promoted. Last but not the least, the local community and visitors should be educated on practical and sustainable lifestyle choices to encourage proper disposal in designated places.

Final Thoughts

Since Nepal’s economy heavily relies on tourism, the degradation of the region’s environment can exacerbate existing problems, leading to a grim future for the land-locked country. The ecological damage Mount Everest is enduring due to climate change is further exacerbated by tourists’ littering, microplastic pollution, and human waste. As Terry Swearingen, Winner of Goldman Environmental Prize in 1977, once said, “We are living on this planet as if we had another one to go to.”

It is true that the popularity of mountaineering gave a way of life that shaped locals’ livelihood, from employment opportunities to renown world record holders. Nevertheless, if we want to keep selling the Everest dream, we have to work more proactively to protect it.

Featured image: Peter West Carey Photography