The imminent mass coral reef bleaching event could be the world in history, experts warn.

—

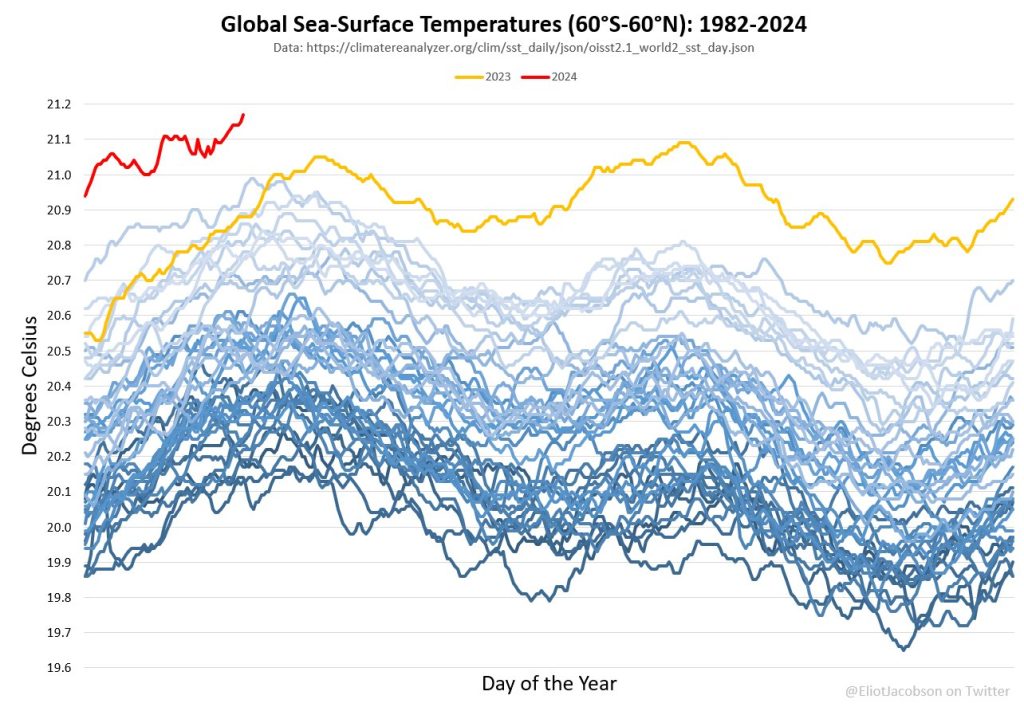

As the global sea surface temperature set a new record high on Monday at 21.17C following months of above-average temperatures, scientists are raising the alarm about a potential fourth mass coral bleaching event.

Speaking with Reuters, the coordinator of the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Coral Reef Watch Derek Manzello said it was likely that the entire Southern Hemisphere would experience bleaching this year.

“We are literally sitting on the cusp of the worst bleaching event in the history of the planet,” the ecologist said.

The risk of a mass bleaching event was recently raised by US and Australian researchers in a paper published in the journal Science, which suggested that last year’s extreme marine heatwaves may be a precursor to a mass bleaching and coral mortality event across the Indo-Pacific in 2024-25.

More on the topic: Coral Catastrophe: Expert Warns of Unprecedented Mass Bleaching in 2024

Disappearing Ecosystems

These important ecosystems exist in more than 100 countries and territories and support at least 25% of marine species; they are integral to sustaining Earth’s vast and interconnected web of marine biodiversity and provide ecosystem services valued up to $9.9 trillion annually. They are sometimes referred to as “rainforests of the sea” for their ability to act as carbon sinks by absorbing the excess carbon dioxide in the water.

Unfortunately, coral reefs are disappearing at an alarming pace. According to the most recent report by the Global Coral Reef Monitoring Network (GCRMN), the world has lost approximately 14% of corals since 2009.

While coral bleaching can be a natural process that occurs due to rising oceans temperatures in the summer months or during natural weather phenomena such as El Niño, a quasi-periodic fluctuation in oceanographic and atmospheric conditions that brings in warm water, a rise in marine heatwaves linked to human activities has led to more frequent and larger bleaching events globally.

One of the best examples of coral bleaching is the Great Barrier Reef, the world’s largest and longest reef system located off the coast of Queensland, Australia; it covers about 350,000 square kilometres – an area that is larger than the UK and Ireland combined. The stunning coral reef system has already suffered six mass bleaching events in 1998, 2002, 2016, 2017, 2020, and 2024. The events in 2016 and 2017 were so severe that they led to the death of 50% of the iconic reef.

Aside from Australia, coral death has been particularly pronounced in regions such as South Asia, the Pacific, East Asia, the Western Indian Ocean, The Gulf, and Gulf of Oman.

While a coral bleaching event does not automatically result in corals’ death, they increase these ecosystems’ vulnerability to marine disease and starvation, which could eventually lead to mortality. The longer corals are bleached under various stresses, the more difficult it will be for algae to return.

More on the topic: Australia Confirms ‘Widespread’ Bleaching Event Across Great Barrier Reef, Blames Rising Ocean Temperatures

Rising Temperatures

Within the last century, sea temperatures have risen at an average rate of 0.13C every decade. Warmer waters make coral reefs more vulnerable to bleaching outside of summer seasons while impeding their ability to naturally recover.

According to the World Meteorological Organization (WMO), sea surface temperatures have been “persistently and unusually high” since May of last year. While this was partly due to the return of El Niño last year, heat-trapping greenhouse gases remain “unequivocally the main culprit,” as oceans absorb more than 90% of the extra heat in the planet’s climate system that results from human-made global warming.

“Ocean surface temperatures in the equatorial Pacific clearly reflect El Niño. But sea surface temperatures in other parts of the globe have been persistently and unusually high for the past 10 months. The January 2024 sea-surface temperature was by far the highest on record for January. This is worrying and can not be explained by El Niño alone,” explained WMO Secretary-General Celeste Saulo.

This story is funded by readers like you

Our non-profit newsroom provides climate coverage free of charge and advertising. Your one-off or monthly donations play a crucial role in supporting our operations, expanding our reach, and maintaining our editorial independence.

About EO | Mission Statement | Impact & Reach | Write for us