The average global surface temperature last month was 14.14C, 0.10C higher than 2016, the previous hottest March on record. Recent trends in global surface air and sea temperatures last month are becoming harder to predict and explain, leaving climate scientists worried.

—

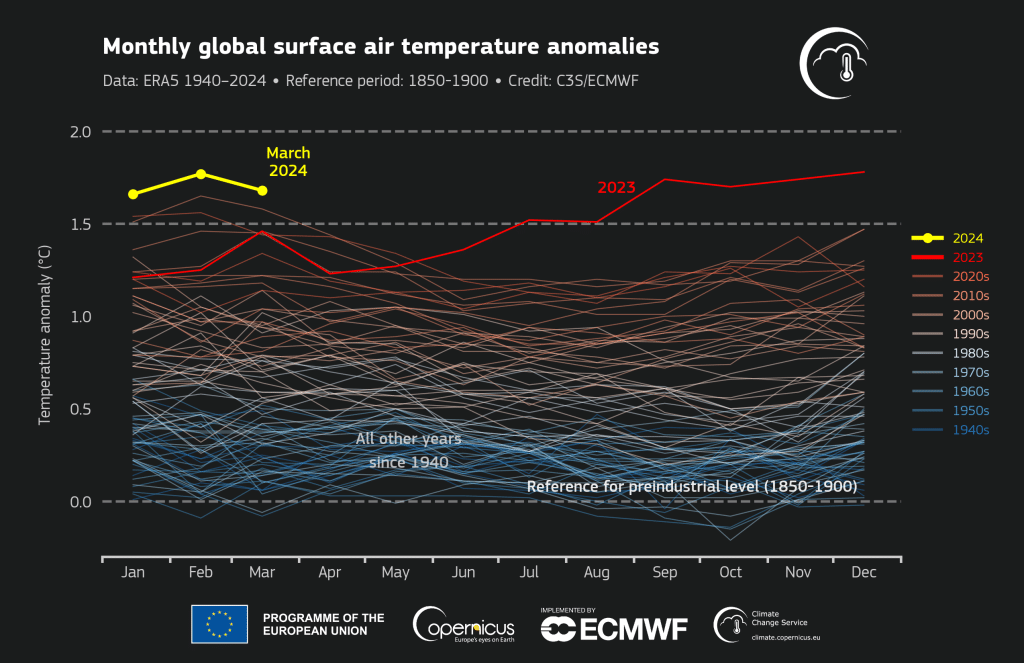

Atmospheric and ocean surface temperatures continued to rise in March, reaching unprecedented levels and marking the tenth consecutive month to break records, scientists have confirmed.

The average global surface temperature last month was 14.14C, 0.10C higher than 2016, the previous hottest March on record.

In a press release on Tuesday, the EU Earth observation agency Copernicus said the global average temperature for the past twelve months is the highest on record, 1.58C above pre-industrial levels and 0.7C above the 1991-2020 average.

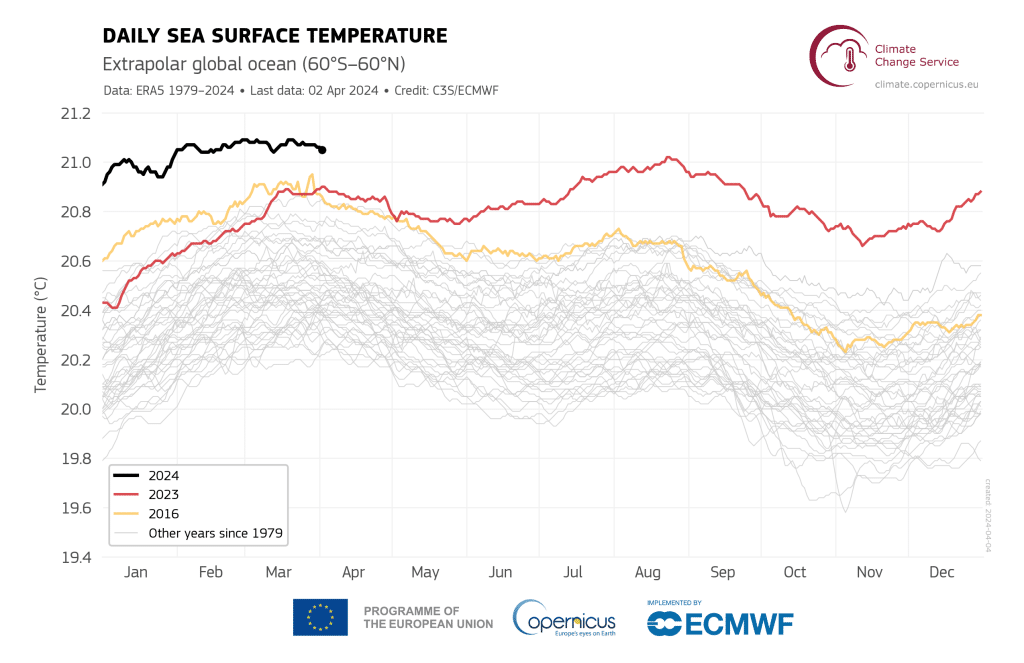

Despite the gradual weakening of El Niño, a weather pattern associated with the unusual warming of surface waters in the eastern equatorial Pacific Ocean that last year brought unprecedented heat across the world, marine air temperatures remained “at an unusually high level,” the agency said. The average global sea surface temperature was 21.07C, the highest monthly value since records began.

In an exclusive interview with Earth.Org, Director of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research Johan Rockström said recent trends in global temperatures are worrying climate scientists.

“We had seen El Niño conditions before, so we expected higher surface temperatures because the Pacific ocean releases heat. But what happened in 2023 was nothing close to 2016, the second-warmest year on record. It was beyond anything we expected and no climate models can reproduce what happened. And then 2024 starts, and it gets even warmer. We cannot explain these [trends] yet and it makes scientists that work on Earth resilience like myself very nervous.”

Wednesday also marked the 400th consecutive day of record temperatures in the North Atlantic.

“There has always been the assumption that the ocean can cope with this, that the ocean is able to absorb this heat in a predictable, linear way, without causing surprise or any sudden abrupt changes. Up until 2023. Because suddenly, temperatures [went] off the charts, and that’s what is so shocking,” Rockström told Earth.Org.

Commenting on the data, Copernicus Climate Service (C3S) deputy director Samantha Burgess stressed once again that only “rapid reductions in greenhouse gas emissions” will stop further global warming.

However, last week the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) confirmed that levels of all three main planet-warming, human-caused greenhouse gases – carbon dioxide (CO2), methane, and nitrous oxide – reached record highs in 2023, albeit growing at a slower pace than previous years.

In a post on X (formerly Twitter) on Tuesday, Climatologist Zeke Hausfather said “the ship has largely sailed on limiting warming to 1.5C at this point.” The comment refers to the most recent data on the planet’s remaining carbon budget, the net amount of carbon dioxide (CO2) we have left to emit before we exceed our desired global temperature increases. In 2015, 195 governments signed the Paris Agreement, setting the threshold for global average temperature rise to 1.5C above pre-industrial levels. But recent developments indicate that, for a 66% chance of meeting the Paris target, we would need to slash emissions from current levels to zero by 2030 or by 2035 for a 50% chance.

“It’s possible to expand the remaining carbon budget by removing more CO2 from the atmosphere than we emit, but even then it’s hard to come up with a plausible 1.5C scenario without overshoot and decline,” Hausfather said.

This story is funded by readers like you

Our non-profit newsroom provides climate coverage free of charge and advertising. Your one-off or monthly donations play a crucial role in supporting our operations, expanding our reach, and maintaining our editorial independence.

About EO | Mission Statement | Impact & Reach | Write for us